Federal Environmental Policies During Pandemic Raise Concerns Across Northwest

READ ON

BY CASSANDRA PROFITA / OPB

State agencies and advocates have been alarmed by federal environmental policy rollbacks that continue unabated by the global coronavirus pandemic.

Amid the COVID-19 national emergency, the Trump administration has finalized rules that scale back the regulations for fuel efficiency in cars and trucks, air pollution coming from power plants and water pollution in streams and wetlands.

Meanwhile, federal agencies announced they would suspend enforcement of some environmental regulations for industries that can’t comply during the pandemic.

In the Northwest, federal officials have also moved forward with controversial decisions on liquefied natural gas development, dam removal, timber sales and Hanford cleanup plans. While agencies note these decision-making processes started long before the coronavirus pandemic, critics argue they should be postponed because it’s too hard for people to follow and challenge them in the midst of a national crisis.

States denounce federal rules

Washington Ecology Director Laura Watson recently denounced the White House for its “relentless attack on the environment” as the presidential administration finalized its Navigable Waters Protection Rule, which lifts water pollution restrictions for many streams and wetlands.

“This is another tragic abdication of federal responsibility to protect the environment,” Watson said in a statement, noting that the decision makes it more difficult for states to protect waterways and runs the risk of state and local taxpayers having to pay to clean up toxic spills.

Oregon Department of Environmental Quality Director Richard Whitman said that state is planning to challenge the administration’s “ill-advised” decision to reduce standards for how fuel efficient cars and trucks need to be in the recent Safer Affordable Fuel Efficient Vehicles rule.

“In my mind, this is really about propping up our petroleum industry, which is hurting now with the pandemic,” Whitman said. “But doing something just to prop up the oil industry in the middle of the pandemic, I will say, grates on us.”

Whitman said the SAFE rule will allow new vehicles to be 20% less efficient and will allow higher emissions than without the rule, setting the state back even further in its goals to address climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions from transportation.

It’s also just a bad time to be changing federal policies, he said.

“We’re all going through a really significant change in how our daily lives work, in terms of our families, in terms of our communities, in terms of the state,” Whitman said. “We’ve got small businesses that are hanging on by their thumbnails here. So, having major changes in federal policy at this time, when the public really isn’t able to engage in the way that perhaps they normally could, does seem a little bit tone deaf to us.”

Oregon and Washington environmental regulators said the decision to relax federal environmental enforcement during the pandemic puts more of the onus on them to make sure industrial facilities are operating properly at a time when their own agency budgets are collapsing because of sharply and suddenly plummeting revenues.

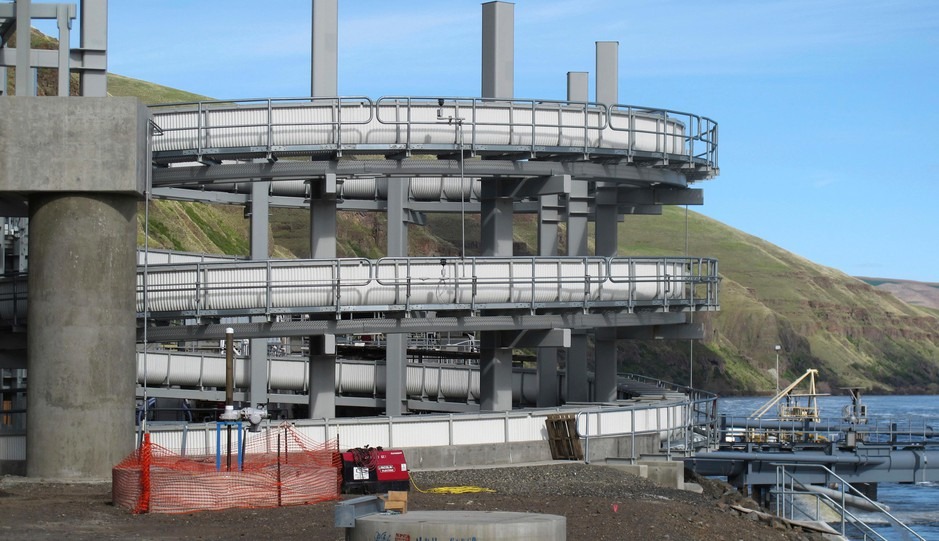

The Port Westward Industrial Park near Clatskanie, Ore. CREDIT: Sam Beebe/Flickr

Leaders from both Oregon DEQ and Washington Ecology also expressed dismay over a recent federal decision to weaken the fish consumption standards that determine water pollution limits in the state of Washington.

Sharlett Mena, special assistant to the director of the Washington Department of Ecology, has counted more than 95 federal environmental rollbacks since 2017, and some of the biggest have been finalized this spring, during the coronavirus pandemic.

The recent decision to change the state’s fish consumption standard, the basis for key water pollution limits, was a huge blow, Mena said.

“They’re very, very big rules,” she said. “All of these rules have gone forth with our very vocal objection and they were finalized now, when we’re flat-footed and we’re worried about our communities. We’re worried about recovery.”

Advocates call foul

Environmental advocates said a litany of new rules that were already controversial are now more difficult to challenge, due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Brett VandenHeuvel, executive director of Columbia Riverkeeper, said he has been watching federal agencies move forward on major projects in the Northwest that his group would normally rally its members to fight in public hearings. But those hearings just aren’t possible while stay-at-home orders are in place.

“It’s frustrating that some of these really controversial projects are moving forward right now at a time when people just can’t engage,” VandenHeuvel said. “Columbia Riverkeeper and many other groups routinely have hundreds and sometimes thousands of our members at public hearings providing really insightful comments and input. By losing that, we’re going to end up with worse decisions and less protection for the environment.”

Federal agencies have moved forward with decision-making on a pipeline for the controversial methanol plant proposed in Kalama, Washington, approval of the Jordan Cove liquefied natural gas project in Coos Bay, budget cuts and cleanup plan changes for the Hanford Nuclear Site near Washington’s Tri-Cities, and the environmental analysis on removing the Snake River dams to help threatened and endangered salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River Basin.

Elliott Moffett, a member of the Nez Perce Indian tribe, holds a sign that reads Free The Snake as he takes part in a rally organized by a coalition of environmental and tribal groups to promote the breaching of dams on the Snake River and other measures intended to benefit salmon and orcas. CREDIT: Ted S. Warren/AP

In March, federal agencies canceled the in-person hearings that had been scheduled on the Snake River dam removal analysis, which rejects removing the dams to save salmon, and replaced those hearings with teleconferences. Thirteen members of the Northwest congressional delegation responded with a co-signed letter to the chair of the Council on Environmental Quality asking for an extension of the comment period and arguing the intensely debated topic could not get the attention it deserves during a global pandemic.

“The current crisis cannot plausibly provide for an environment conducive to robust public comment,” they wrote. “Public feedback should be solicited in an accessible manner and, crucially, in-person, so that the citizens who stand to be affected most directly can make their voices heard to the officials charged with making these decisions.”

The request was not granted, and the comment period is now closed.

Meanwhile, VandenHeuvel said he’s worried that the federal agency in charge of enforcing protective environmental laws is allowing more pollution to be released from industrial operations such as oil refineries, pulp and paper mills and mining sites across the region.

“They’re essentially the police force for pollution,“ VandenHeuvel said. “We’re seeing simultaneously that they can’t do their jobs to enforce environmental laws, but they can push forward dirty pollution-causing projects that the Trump administration’s cronies in the oil industry want to see move forward.”

Agencies adjust to pandemic

In a written statement, an EPA spokesperson said the agency is still enforcing environmental laws while allowing some violations of pollution monitoring and reporting requirements because of the coronavirus pandemic.

“Given the fact that millions of facilities are regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency, under EPA’s temporary policy a facility does not have to wait for EPA approval to implement worker protections that could impact compliance with routine monitoring and reporting requirements,” an agency spokesperson said in a written response to OPB. “The temporary policy clearly states that the burden is on the regulated entity to demonstrate that its noncompliance was caused by the COVID-19 public health emergency.”

The EPA said companies are still required to report any violations of their permits, or of regulations and laws, and to notify authorities of operational failures that could increase pollution and pose imminent threats.

“Where noncompliance has these impacts, enforcement discretion, if any, will be determined on a case-by-case basis, depending on the circumstances,” the EPA said. “The policy has no leniency for those who exhibit an intentional disregard for the law or for accidental releases of oil, hazardous substances, hazardous chemicals, hazardous waste or other pollutants.”

U.S. Forest Service media officer Stephen Baker said his agency remains operational during the pandemic and is keeping national forests open to logging, grazing and other economic activities to support local and rural economies. The agency has 400 open contracts for work in Oregon’s national forests and 30-35 active timber sales.

“We continue to support timber, forest products, grazing, infrastructure projects and other sustainment and economic uses of our forestlands where these activities can be carried out safely for our employees, contractors, permittees and the public,” he said.

Beyond the borders of the Kalmiopsis Wilderness are as much as 200,000 acres of undeveloped forest. CREDIT: Ian McCluskey/OPB

George Sexton, conservation director with Klamath-Siskiyou Wildlands Center, said he’s concerned about logging projects, like the Blown Fortune timber sale on Bureau of Land Management land, that aim to remove old-growth timber while federal offices and public lands that serve as recreation sites are largely closed.

“I fear that converting these older forest types into dense young timber plantations will increase fire hazard moving forward,” he said. “I’m also concerned that while BLM hydrologists, biologists and recreation planners are being told to stay home, that the timber staff remains on the job.”

BLM public affairs officer Sarah Bennett said her agency is continuing timber sales and agency staff are monitoring that work while maintaining safe social distance.

The BLM has closed its offices to walk-in visitors and has closed developed recreation sites and parking lots at popular trails to minimize crowds, Bennett said, but it has kept some trails and public lands open to local recreation and is allowing office appointments as needed.

“We are encouraging people to stay local to where they live to avoid putting strain on rural communities that are often located near BLM public lands,” she said. “We’re working hard to maintain our services to the public, visitors and stakeholders while ensuring the safety of everyone involved.”

Copyright 2020 Oregon Public Broadcasting. To see more, visit opb.org

Related Stories:

Washington state, federal agencies finalize agreement for tank waste cleanup at Hanford

Hanford workers take samples from tank SY-101 in southeast Washington state. (Courtesy: U.S. Department of Energy) Listen (Runtime :59) Read When it comes to tank waste at Hanford in southeast

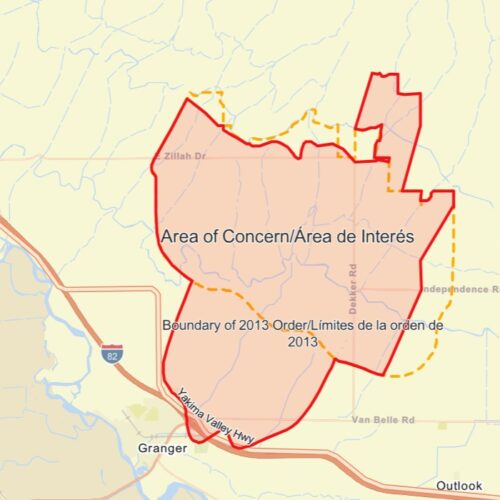

Federal judge orders Yakima County dairies to test wells, drinking water

A federal judge in Eastern Washington granted a preliminary injunction in a lawsuit that

involves over ten Yakima County dairy producers.

After years of negotiations, new government Hanford plan stirs up plans to treat radioactive waste

A 2021 aerial photo of Hanford’s 200 Area, which houses the tanks and under-construction Waste Treatment Plant, in southeast Washington. (Credit: U.S. Department of Energy) Listen (Runtime 1:01) Read There