The Enduring Afterglow Of Ravi Shankar’s Life In Music

LISTEN

BY BILAL QURESHI

Indian Sun is a new authoritative biography of the Indian musician Ravi Shankar‘s life, published to coincide with this year’s centenary of his birth.

In a career that spanned decades and continents, Ravi Shankar single-handedly introduced Western audiences to the centuries-old classical tradition of Indian Ragas — a complex system of melodies performed as longform improvisations by an instrumentalist and an accompanying percussionist. He inspired legions of fans and created a model for stretching the boundaries of an ancient musical tradition.

Biographer Oliver Craske traces the full breadth of Shankar’s life beyond the known flashpoints of his career – icon of the 1960s, teacher of George Harrison and a tour-de-force set at the Monterey Pop festival.

Pictured here in his late 20s, Ravi Shankar was hugely important in popularizing Indian classical music in Western pop music. He would have turned 100 years old today.

CREDIT: Courtesy of the Shankar family

Shankar’s road to Western stages began much earlier in his life as he toured Europe with his brother Uday Shankar’s dance troupe.

“He keeps cropping up in these amazing moments in history, whether it’s growing up in India under the British Raj or touring Germany just as Hitler is coming to power, visiting The Cotton Club in New York at the time of Prohibition,” Craske says. “It was a kind of education that no other Indian classical musician had. It made him completely comfortable with presenting Indian music to a global audience.”

At the height of what Craske calls the West’s ‘Sitar explosion” of the late 1960s, Shankar grew ambivalent with the lazy understanding of his sacred music, especially the cliché associations of Ragas with drugs and psychedelic kitsch. Craske says he “had a bit of recoil from playing pop festivals and in the ’70s, he decided to reset his career and to be booked by classical promoters thereafter.”

Shankar demanded rigor and attention from audiences but also consistently challenged and stretched himself with new collaborations and experimentations.

“He’s famous for working with Yehudi Menuhin, Philip Glass, Zubin Mehta, but for me the common theme running through that is that he was essentially playing Indian music,” Craske says. “He wasn’t a fusion artist who throws together two different forms; essentially, he was using different formats as ways of playing Indian music. It wasn’t just jamming aimlessly. He was very serious in that way.”

Shankar’s success was not without its detractors. Oliver Craske’s biography illuminates how his contemporaries at home in India, including the acclaimed Sitar player Vilayat Khan, criticized his international ambitions and perceived dilutions.

For acclaimed British Indian composer Nitin Sawhney, who knew and idolized Ravi Shankar, the tension between traditional purists and innovation remains a cyclical question.

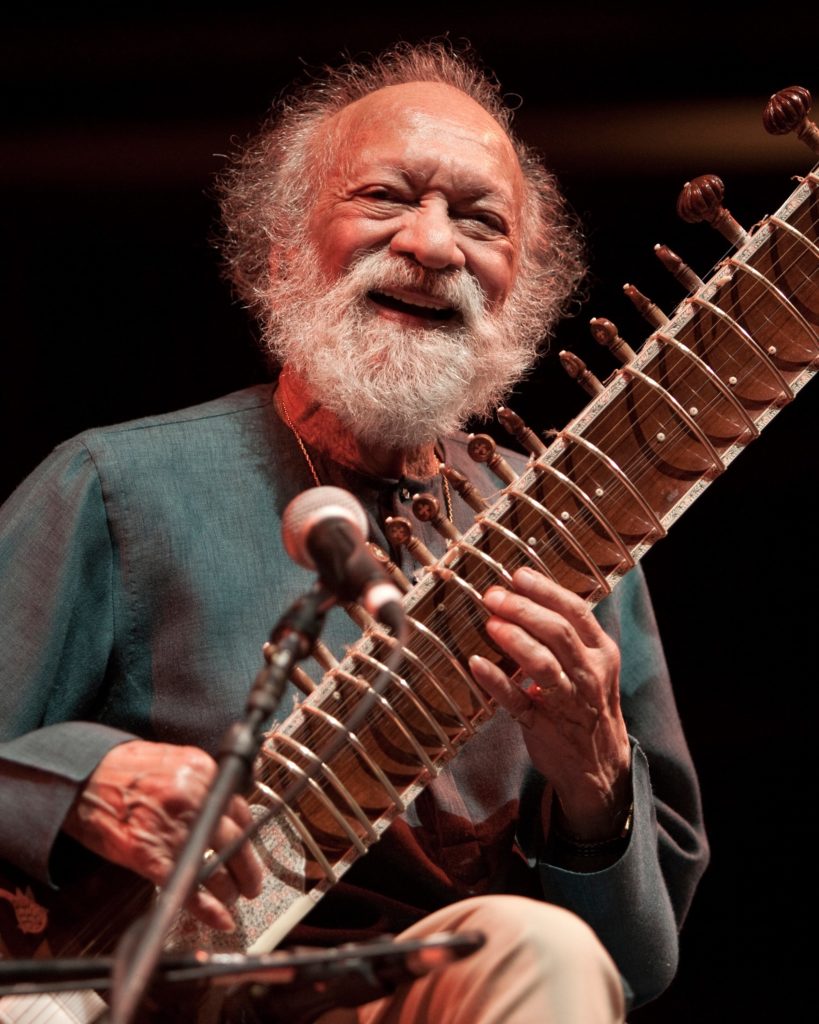

Ravi Shankar performs at the age of 91. CREDIT: Michael Collopy/Courtesy of the artist

“He was a great inspiration to me as someone who was always thinking about possibility,” Sawhney says. “He always recognized that every tradition is dynamic and it is still dynamic to keep its relevance in contemporary society. And a lot of people interpret tradition as dogma and that’s very different to how he thought.”

Ravi Shankar’s last recorded concert was a three-hour performance delivered on the eve of his 92nd birthday. It would become his musical farewell to his home country and to the cultural font of his life’s work, India. At the heart of the Live in Bangalore concert album are Sitar duets by the international elder of Indian classical music and his daughter and student, Anoushka Shankar. With his health failing in his final year, she describes how she could feel him passing on the torch.

“It was a great learning curve for me because he was increasingly relying on me a bit more,” Anoushka Shankar says. “He would be improvising and you never knew when he was going to let go of line. He’d also do this on purpose to challenge me as well. He would literally play half a line and I would need to be able to catch it and play something that made sense, authentically.”

Anoushka Shankar, whose own solo career has included experimentations with flamenco and electronica, says her father modeled an approach to collaboration rooted in tradition.

“There’s something really inspiring about being really rooted in order to find our freedom of who we are. What really stays with me about my father is how deeply rooted his music was, and then from that rootedness, how expansive and free his creativity was,” she says. “He was simultaneously the most knowledgeable person I knew when it came to the intricacies of a deeply, deeply complicated musical style, but he was also the most creative human being I know. It was like a tap for him and he could endlessly create.”

A few weeks after he passed away on Dec. 11, 2012, Anoushka Shankar and her half-sister Norah Jones accepted their father’s posthumous Lifetime Achievement Grammy together on stage.

The following year his daughters Anoushka Shankar and Norah Jones released a song called “The Sun Won’t Set.”

“My dad’s name, Ravi, translates as ‘sun’ in Sanskrit and I was writing it in those months where he wasn’t well and I didn’t quite feel ready to let go of him,” Anoushka says. “So I was just speaking about that idea of not wanting the sun to set yet. And it was beyond perfect to have Norah sing the words.”

Anoushka Shankar says in the first years after his death, she and her mother, his wife Sukanya Shankar, were still grieving and she found it difficult to commemorate him in a more public manner. But today would have been Ravi Shankar’s hundredth birthday and on a more celebratory note, Anoushka Shankar had planned a series of centenary concerts around the world – including her first live performance with her sister Norah Jones. While those concerts had to be postponed in light of the pandemic, she gathered some of her father’s students online on April 7, his birthday, for a joint performance of one of his original compositions.

Beyond his restless devotion to expanding the audience for Indian music and his template for multicultural fusions, Ravi Shankar’s most tangible legacy is the enormous collection of recordings and concert performances he left behind. Many of the Ragas he recorded on stage have been performed for centuries and will continue to be studied and re-imagined by future generations.

Composer Nitin Sawhney says in the current age of lockdowns, there is a lesson to be drawn from Ravi Shankar’s devotion to music and its spiritual possibilities.

“There’s the whole process of Riyaaz, where a great Indian classical musician will go into a hermetic state and will be just on their own for many years, practicing, which is something that he did,” Sawhney says. “That whole idea of meditation and isolation and also being creative and constructive with that time is very, very important for all of us and we can all hear the fruition of all of that in every piece of music he ever created. So in that way, he can be an inspiration to all of us.”

9(MDAyOTk4OTc0MDEyNzcxNDIzMTZjM2E3Zg004))