There is no cure or vaccine for COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus that has sickened more than 1.4 million people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization, and killed an estimated 100,000. But health care workers have been trying to reduce the severity of people’s symptoms with medications designed to treat other ailments — including the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine.

While there is anecdotal evidence hydroxychloroquine has helped manage some patients’ symptoms, there is no data that proves it is effective in treating or preventing COVID-19.

The National Institutes of Health has launched clinical trials around the drug as a potential therapy for COVID-19 at Vanderbilt Medical Center in Nashville and a network of more than 40 hospitals. But absent that kind of data, there has been confusion around how exactly to use the drug to treat patients sick with the virus — and whether it is effective.

For weeks, President Donald Trump has touted the use of the drug, along with chloroquine, as possible treatments. Often, he has suggested combining them with antibiotics.

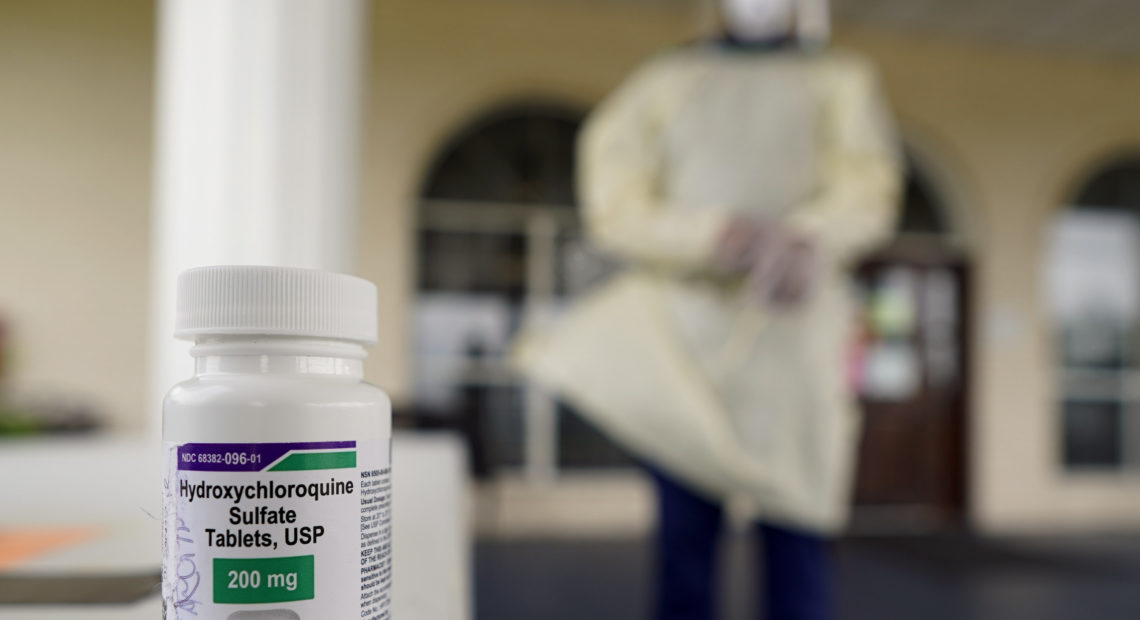

A bottle of hydroxycloroquine sits on a table outside the entrance to The Resort at Texas City nursing home, where Robin Armstrong, a doctor and the home’s medical director, is giving the drug to residents

CREDIT: David J. Phillip/AP

During the April 7 task force briefing, Trump told the story about a Michigan woman sick with the virus who then asked her husband to pick up hydroxychloroquine. Her condition improved, Trump said, adding that the woman later “thanked me.’”

“Look, I don’t say that happens with everybody, but that’s a beautiful story. There are many of those stories. And I say, “Try it,” Trump said during the April 7 briefing.

Public health officials have criticized Trump for pushing a drug without evidence of its efficacy in treating COVID-19, and Dr. Anthony Fauci, who has led the nation’s response to the virus, has said there is no data to support that this drug works.

The president’s endorsement has emboldened at least two people to take chloroquine, absent a doctor’s orders, with tragic results. One Arizona couple consumed chloroquine phosphate, a chemical used to treat sick fish in their koi pond. Both in their 60s, the man and woman became ill, and the man later died, NBC News reported on March 23. They were afraid they would get sick with COVID-19, and ingested the chemical after President Donald Trump touted its possible benefits, according to the woman, who asked not to be named when she spoke to NBC News.

Here’s what we know about the drug now and how researchers are working to determine if it truly can help patients infected with novel coronavirus.

What is hydroxychloroquine, and what does it treat?

Centuries ago, the Incas in Peru dried and ground cinchona tree bark, then mixed the resulting fine powder with a liquid. In doing so, they produced a medicine used to lower fever later called quinine.

By World War II, researchers studied how to further develop quinine for antimalarial treatment, eventually creating chloroquine. Among soldiers who were administered these drugs, those with rashes and arthritis noticed their symptoms improved, paving the way for this antimalarial medication to also be prescribed to reduce swelling and joint pain. By 1955, a synthetic and less toxic version of this drug, hydroxychloroquine, had become more widely available.

Because hydroxychloroquine reduces inflammation, doctors have often prescribed it to treat rheumatoid arthritis, as well as lupus, sarcoidosis and other autoimmune diseases. Side effects tend to be mild and include nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, but if the drug is taken for long periods of time, a rare eye disorder called retinopathy may develop, resulting in permanent vision loss. Patients in the United States often refer to hydroxychloroquine using the brand name, Plaquenil.

Is hydroxychloroquine a safe treatment for patients with COVID-19?

At Vanderbilt Medical Center in Nashville, Dr. Wesley Self said he has lost count of how many patients he has treated for COVID-19. To find better ways to take care of those patients, Self is serving as lead investigator for the nationwide clinical trial on hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19. On Thursday, the National Institutes of Health formally announced the trial.

Researchers started enrolling trial participants on April 2, Self said. There is reason to think hydroxychloroquine could reduce swelling in the lungs of a person with the virus, Self said.

ALSO SEE: Coronavirus News, Updates, Resources From NWPB

But people with COVID-19 are taking many medications, and those medications may interact with each other in unexpected ways. On top of that, Self said people infected with the virus “may be more susceptible to side effects from medications.”

“There’s promise for this drug, but we simply don’t have enough data in patients with COVID,” he said.

To understand whether or not the drug might help COVID-19 patients, Self and his research team are conducting a randomized trial. That means some patients infected with the coronavirus will receive hydroxychloroquine, and some won’t.

File photo. President Donald Trump speaks during a press briefing with the coronavirus task force at the White House. CREDIT: Evan Vucci/AP

Those who do get hydroxychloroquine will receive the medication for five days. The research team will then compare which group of patients get better faster and which ones may have reactions and side effects from the drug, Self said. And investigators, medical teams and patients won’t know which patients get the medication, ensuring that — all else being equal — every patient gets the same level of care. The trial is expected to last several months, or until researchers see definitive evidence that the drug is or isn’t helping.

“We know this is an emergency, so we were already working very quickly,” Self said. “We’re trying to run this study as fast as we can while making sure it is still safe.”

Until researchers complete these trials, anyone touting the benefits of using these drugs is only speaking anecdotally. These trials “are the way we learn,” said Dr. Richard Schilsky, chief medical officer for the American Society of Clinical Oncology and an expert on clinical trials. If the study is well-designed and conducted, the findings won’t be based on hearsay or intuition but scientific observation.

Until then, it remains unclear if these antimalarial medications offer effective treatment and relief during the COVID-19 pandemic. And no one should take these medications without consulting with their health care provider.

What about people who take hydroxychloroquine to treat other conditions?

The Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency use authorization on March 28 for hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate. That made it available to public health authorities to tap into the Strategic National Stockpile’s supply as an option for treatment

The next day, the Department of Health and Human Services accepted 30 million doses of hydroxychloroquine and one million doses of chloroquine to the Strategic National Stockpile, donated by Sandoz and Bayer, two pharmaceutical companies.

“Anecdotal reports suggest that these drugs may offer some benefit in the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients,” a department press release said. “Clinical trials are needed to provide scientific evidence that these treatments are effective.”

Even before confirmation from clinical trials, demand for hydroxychloroquine has led to shortages for people prescribed to take the drug to treat other illnesses. Health care providers are warning that could be a dangerous problem on its own.

“Treatment interruptions for those with SLE and other rheumatic diseases must be prevented, because lapses in therapy can result in disease flares and strain already stretched health care resources,” Drs. Jinoos Yazdany and Alfred H.J. Kim, wrote late last month in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Autoimmune disease patients like James Kuhn said they fear they will have trouble filling prescriptions for a medication that they have relied upon for years.

Kuhn, who has taken the medication as his primary therapy for 10 years to treat sarcoidosis, a rare disease that swells lymph nodes and organs, and Sjogren’s disease.

ALSO SEE: Coronavirus News, Updates, Resources From NWPB

Kuhn, who also volunteers as a patient advocate, refilled his prescription in mid-March. But he is worried when he hears that some pharmacists are scaling back 30- or 90-day prescriptions to just two weeks. That could mean immuno-compromised people like Kuhn must venture outside their homes more often and potentially expose themselves to novel coronavirus to get the medications they need.

“If we catch the disease, it is a near-death sentence,” Kuhn said.

His rheumatologist, Dr. Soha Mousa, has been consulting with her patients, including Kuhn, by telemedicine since the pandemic began, and they are telling her they are already having a tough time filling prescriptions for hydroxychloroquine. In some cases, pharmacies ask patients to provide proof of their diagnosis before receiving their medication, Mousa said.

“I’m getting frantic messages, [like] ‘How am I going to survive?’” Mousa said.

Mousa said she is asking her patients to shop around, if possible. Find different pharmacies, or shop online for their prescriptions of hydroxychloroquine. They have told her that in some cases, it now costs $600 to fill a month’s prescription, dramatically more than what the drug cost even three months ago. For some patients, that prices them out of their medication.