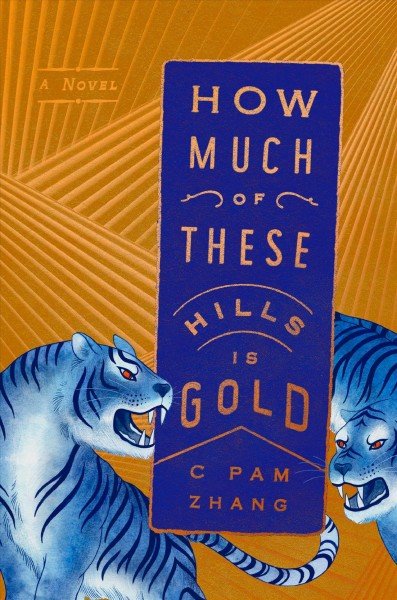

BOOK REVIEW: In ‘How Much Of These Hills Is Gold,’ This Land Is Not Your Land

BY ANNALISA QUINN

Like William Faulker’s As I Lay Dying, C Pam Zhang’s debut novel opens with a body in need of burying.

In How Much of These Hills is Gold, Lucy and Sam, 12 and 11, children of Chinese laborers, take their father’s body on a journey through the California hills in the middle of the Gold Rush. The quest for burial, the family strife, the smell of death, the hot sun, the dust, the storms, all recall Faulker. Ba (Mandarin for “dad”) haunts the narrative as Addie Bundren did, first as voice and then ultimately as a corpse, awful, unwieldy, and decomposing.

Burial is one of the ways we mark land as ours, that we claim ancestry and belonging. So it makes sense that Lucy and Sam wander for weeks, looking for a place that feels like it could be a (literal) fatherland. “This land is not your land,” reads the book’s epigraph, and that’s the message they receive again and again, from other children, from the miners, from the law, which strips their family of the right to own the gold they find in the hills. (Through the novel, mining and burial form countermelodies, as if Zhang is asking what makes a piece of land home: what you put into it, or what you take out of it).

How Much of These Hills Is Gold

by C Pam Zhang

Zhang’s style can be densely, airlessly lovely. Self-conscious lyricism fills the page like all that California dust, sometimes making it hard to breathe: “Ma starts to laugh. Laughter that’s closer kin to rage than joy, laughter like a consuming. Lucy thinks again of fire. But what’s being burned?”

The novel also depends so heavily on foreshadowing that it feels like we might be in a de Chirico painting. For Zhang’s characters, any good thing — a baby, a new friend, sudden money — spells disaster, a feature which drains suspense and makes it impossible to sustain any hope for them. To read this novel the way it wants to be read — earnestly, wholeheartedly — would be to be in a perpetual state of longing and disappointment. John Steinbeck once wrote to his editor about the Grapes of Wrath, a clear inspiration for this novel: “I’ve done my damnedest to rip a reader’s nerves to rags.” With Zhang, we hear the shredders coming from miles away — and it’s hard not to resent that emotional manipulation.

But Zhang also unspools sophisticated ideas about land, ownership, rootedness, and history. The local schoolmaster, Teacher Leigh, takes an interest in Lucy because he wants to write her into his flattening, exoticizing ethnography. As she gets older, she realizes how much unspoken history is left out of books like his.

For their family, America was supposed to be a land of abundance. Instead, they find “a land of missing things. A land stripped of its gold, its rivers, its buffalo, its Indians … its birds and its green and its living.”

But it was “easier to avoid that history, unwritten as it is except in the soughing of dry grass, in the marks of lost trails, in the rumors from the mouths of bored men and mean girls, in the cracked patterns of buffalo bone,” Zhang writes. “Easier by far to read the history that Teacher Leigh teaches, those names and dates orderly as bricks, stacked to build a civilization.”

This novel is clearly meant to be a counter to those orderly histories, which leave out what was there before “progress” came to California’s hills, and what was lost when it did. “Those gold men really think this land belongs to them,” says Sam. “Isn’t that the greatest joke?”