Julia Alvarez: Literature Tells Us ‘We Can Make It Through’

LISTEN

BY SCOTT SIMON

Julia Alvarez has written what she calls her first novel as “an elder.”

“It took a while to sort of process this stage of life that I’m in,” she says. “And you know, what are the stories that I can tell now, from the hindsight and the insights that I’ve gained that is different. And you have to, you know, learn that.”

The author of beloved and bestselling novels for adults and children, including How the García Girls Lost Their Accents and In the Time of the Butterflies, has brought out her first novel for adults in a decade and a half.

It’s called Afterlife, and it’s about widowhood, sisterhood, and opening hearts to “the others.”

Interview Highlights

On real life interrupting plans — in life and in the novel

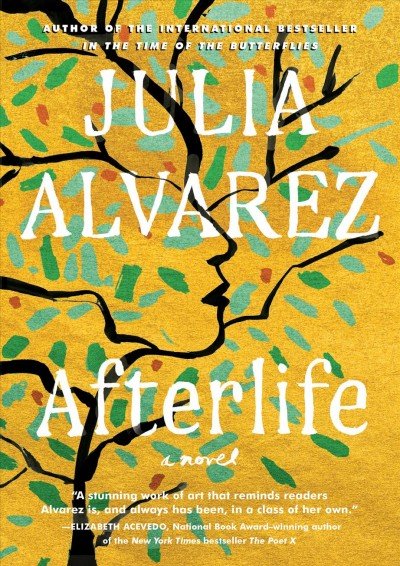

Afterlife

by Julia Alvarez

It’s amazing. And I’ve been thinking a lot about that, because I’ve read a few other novels just published — and I think then also about Afterlife, that I think in some ways writers pick up the zeitgeist, that somehow there was already some sense of impending losses and doom, whether it’s environmental, with what we’re seeing with climate change and losing species. And in addition, you know, the divisiveness that we’re seeing, the gun violence, what’s happening at the borders, this sense that there was so much that was falling apart, so many losses.

On what we owe to each other — should you really put your own oxygen mask on first?

Well … the thing that we are realizing, and that was never said, is that we need to share those oxygen masks. We all go down together on this if we don’t come together. I think it can be such an opportunity for all of us. You know, Wordsworth, in a poem he wrote later in his life, says “A deep distress has humanized my soul.” And it’s about the loss of his brother. But it is, you know — I think about that line, that this huge distress, deep distress might humanize us and return us to the good people that we are. And at the same time, I’ve got to say this too, Scott, it feels kind of weird to be talking about my novel, and somehow promoting it, at a time like this … just doesn’t quite feel right, because as you know, it’s not business as usual.

On what reading can do right now

It’s always been something that reading is about — it’s about being together, apart. I’ve thought a lot about, because that phrase has been bandied and I thought, well, now that’s a definition of reading. And I think what I’ve always felt with books that I’ve loved, and what I would want my readers to feel is accompanied. And that’s finally why I turned to writing, for that deeper connection, and for that deeper sense of belonging.

On how great works of literature can seem prescient

I return to those works, because in a sense, it says to me that this has happened before. We can make it through. You know, this is Robert Frost country, and he has a wonderful poem, “Directive.” At the end of the poem, he says, “Here are your waters and your watering place. Drink and be whole again beyond confusion.” And he’s talking about, you know, searching for this little cup in the woods, this holy grail. But he’s talking about literature — literature I use in the broad sense. I don’t mean just written stories. I mean oral stories. I mean music. I mean dance. All these things people are seeking solace in. Here are your waters and your watering place. Drink and be whole again beyond confusion.

This story was edited for radio by Ed McNulty and Nuria Marquez Martinez, and adapted for the Web by Petra Mayer.