Jay Inslee Vetoes $235M In Washington Spending As Coronavirus-Caused Fiscal Cliff Looms

READ ON

In anticipation of state revenues cratering because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee on Friday vetoed more than $200 million of new spending from the supplemental budget passed by state lawmakers last month.

Among the bigger ticket items Inslee eliminated was more than $100 million to hire 370 more school guidance counselors statewide and $35 million for para-educator training.

Also on the nine-page list of 147 operating budget vetoes was funding for a new Washington State Office of Equity, money for a gang violence reduction pilot project in eastern Washington and funding for additional body scanners in state prisons. Over four years, the savings are expected to total $445 million.

“These are not normal times and we cannot sleepwalk our way through this fiscal crisis,” Inslee said at a bill signing ceremony Friday afternoon.

However, Inslee left intact approximately $600 million in fresh spending, including approximately $200 million to address homelessness and housing, which he views as essential to the COVID-19 emergency response. That money will fund such things as rent assistance, permanent supportive housing and new shelter beds.

Also left untouched was the $200 million lawmakers unanimously agreed to take from the state’s constitutionally-protected “rainy day” account to fund the state’s response to coronavirus.

The unusual move to pare back spending mid-biennium by veto pen comes as Inslee and state leaders brace for a major downturn in the economy and a resulting rapid decline in state revenues. Already economists are predicting the COVID-19 crisis will trigger the “worst recession” the United States has seen in modern times.

“Absolutely, it looks worse than the Great Recession in an enormously quick timeframe,” said state Sen. John Braun, the ranking Republican on the Senate Ways and Means Committee.

States like Washington that are especially dependent on sales tax revenues could be especially hard hit.

As one indicator of the economic carnage already, unemployment claims in Washington and across the country have skyrocketed to never-before-seen levels, with 182,000 Washingtonians filing first-time claims for jobless benefits last week.

Before leaving town in mid-March, majority Democrats approved $961 million in new spending as part of their update to the state’s two-year, roughly $53 billion operating budget. At the last minute, as the threat of the coronavirus pandemic loomed, Democrats retooled their budget to leave more money in unrestricted reserves. But they didn’t dramatically downsize their new spending plan.

“We built it to be recession proof, but we did not design it to be global, economic meltdown proof,” said Democratic Sen. Christine Rolfes, who chairs the Senate Ways and Means Committee.

Rolfes praised Inslee’s decision to start pulling back on spending now, but cautioned it’s just the “first steps” in what’s likely to be months of difficult budget decisions in the months ahead.

Braun, the Republican budget writer, said he appreciated Inslee’s “modest” budget vetoes, but added that they didn’t go far enough.

“I would have liked to see him do more because I think we’re going to have a very large budget challenge on our hands and reducing future spending today is going to be much, much easier than cutting services either in a special session or a future session,” Braun said.

So far, Inslee and state legislative leaders don’t see the need for an immediate special session of the Legislature to further cut the budget. But Rolfes said she expects a special session will eventually be needed – perhaps in the fall.

In the short term, Washington may have a bit of a buffer. The state’s restricted and unrestricted reserves through the end of the biennium are projected to be nearly $3 billion. But preliminary projections shared with legislative budget writers suggest the state could lose $3 billion to $6 billion in projected revenues in that same timeframe.

“The estimates are big and they’re broad and they’re unknown,” Rolfes said.

Better estimates may come on April 30 when the state’s revenue forecaster, Steve Lerch, is expected to provide an unofficial forecast at a meeting of the State Revenue Council. The next official forecast is scheduled for mid-June.

What’s clear is Inslee’s initial paring back of spending is just the start of what may ultimately become dramatic reductions in state spending. Unlike Congress, state lawmakers are required to write balanced budgets and are not allowed to engage in deficit spending. In Washington, the bar is even higher with a requirement that the two-year budget balance over four years.

While spending on public schools is constitutionally protected, the brunt of any future cuts could be borne by prisons, higher education, community colleges and even state subsidized child care programs. In a worst case scenario, the state might also freeze hiring and even furlough workers, something that happened during the Great Recession.

Washington’s budget has grown dramatically in recent years, fueled by an unprecedented streak of positive quarterly revenue forecasts, along with demands to fully fund public schools and address the state’s mental health crisis. For instance, the current 2019-21 budget spends $8 billion more than the previous biennial budget.

But much of that new spending could now be imperiled as state budget writers shift from a where-to-spend posture to one focused on where-to-cut to balance the budget. Unknown at this point is whether federal relief funds could soften the blow to state budgets.

While it took years for the state, and the nation, to recover from the Great Recession, there’s some hope the economic recovery from the coronavirus crisis will be more V-shaped. Regardless, Rolfes said the state is, in some respects, better equipped today than it was a decade ago to weather a recession.

Besides the state’s rainy day fund and the four-year balanced budget requirement, she pointed to the Affordable Care Act, the state’s new paid sick leave program and a “robust” unemployment system as elements of an economic safety net.

“People should be confident that they will have their unemployment benefits and we should be able to provide everybody with healthcare while they’re looking for work or waiting to get back into the game,” Rolfes said.

Related Stories:

Washington state bill could strengthen regulations, increase fines for ‘troublesome’ landfills

While hiking, Nancy Lust, with Friends of Rocky Top, watches a truck dump waste into a landfill in Yakima County. Lust lives near the landfill and has fought to learn

This bill could give Washington tribes, communities more say in wind, solar development

A new bill making its way through the Washington Legislature would require county and tribal approval for new wind and solar projects that go through the state’s Energy Facility Site

Washington state bill could change how rural communities could work to close a library

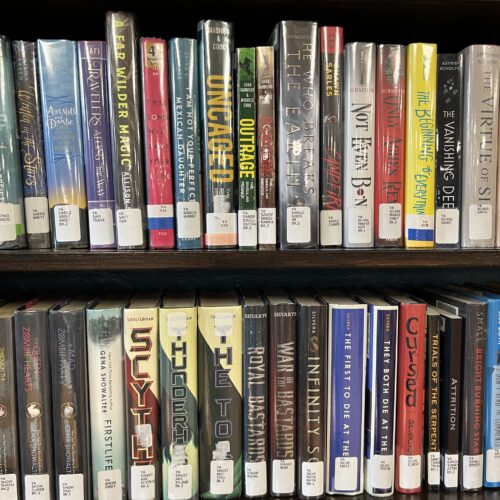

Young adult books at the Columbia County Library. Some people have requested to move the YA section into the adult section because of what they call “obscene” material in 100