Feisty. Ambitious. Lucky. Female Writers On The Words That Undermine Women

LISTEN

BY AILSA CHANG

What does it mean to call a woman ambitious, disciplined, mature, or feisty?

A new essay collection explores how these words, which may sound complimentary, are loaded with sexist ideas that diminish the women they describe.

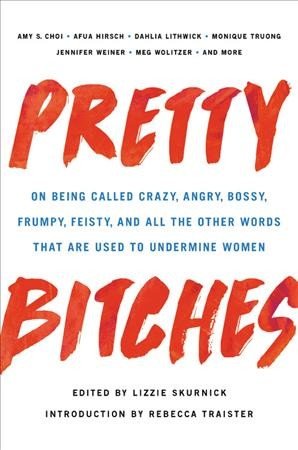

Pretty Bitches, edited by Lizzie Skurnick, examines how everyday language creates double standards in the workplace, raises unrealistic expectations about how women should behave and look, and punishes them when they step outside the bounds.

When Skurnick approached writers to contribute to the book, she found that each woman had a word that had been bothering them — consciously or unconsciously — for a long time. Sweet. Aloof. Tomboy. Crazy. Professional. Lucky. Effortless.

“These words are code for actions people are going to take,” Skurnick says. “So when someone calls you shrill, it means they’re not going to give you the job. If somebody calls you mature when you’re a young girl, that means they’re hitting on you in a really slimy way. … If someone calls you lucky … they’re saying you do not deserve what you have.”

Pretty Bitches:

On Being Called Crazy, Angry, Bossy, Frumpy, Feisty, and All the Other Words That Are Used to Undermine Women

Edited by Lizzie Skurnick

Words are powerful Skurnick says, and it’s important to acknowledge the ways language is used to undermine women.

“I felt like if we can’t talk about these words, we’re not going to be able to understand the power they’re having in the world and that they’re having over our lives,” Skurnick says. “And that’s very dangerous for us right now.”

The 2016 presidential election helped spur Skurnick to work on the book. She said no matter where she looked, she saw descriptions of Hillary Clinton as a “flawed” candidate.

“So someone is ‘flawed,’ — that’s why you don’t have to vote for them. …” Skurnick says. “These words are so powerful they’re actually doing things to us in the real world and we have to talk about them. It has nothing to do with our feelings. It has to do with what is being done to us.”

Interview Highlights

On Amy S. Choi‘s essay about the word “effortless”

There is, you know, there’s a huge Catch-22. You’re not allowed to exist as a woman in the world without being beautiful … but if you make too much of an effort to be beautiful, you’re also not beautiful. So, it all has to be “effortless.”

You’re locked in this endless cycle of labor and covering up that labor. And while you’re doing that, men are just wandering around, you know, founding institutions, doing experiments, winning at poker. They have all this free time to be living their lives while we’re sitting there, you know, microblading our eyebrows.

On Glynnis MacNicol‘s argument that women who achieve success through hard choices and hard work are threatening the status quo — and so society attributes their success to “luck”

If we like having our bank accounts, if we like working in jobs where we’re authoritative, if we like going out to dinner alone, then what the hell is going to happen to the patriarchy? You know, it’s going to be knocked down. What we have to say is that when a woman has worked hard, that she’s “just lucky” — that this just happened to her. It’s less threatening. …

At one point [MacNicol] gets two book deals I think within 13 months or something. And, you know, she’s able to go on these trips because she doesn’t have children. And she budgets, and she works hard to be able to do it. But all that happens on Facebook is everybody says, “Oh, you’re so lucky, I’m jealous.” And, you know, she thinks: Would they really say that to a man? They would say something like: Nice to see all your hard work paying off.

On how journalist Afua Hirsch hears the word “professional”

When she was becoming a barrister, she had no doubt that she needed to straighten her hair to look as much like a white man as possible. … She finally gave it up after somebody said, you know, your legs look too muscular. And she said, all right … saying I’m “unprofessional,” is just code for saying I’m black. And if somebody is getting mad at me for being black, I can’t be unblack. But I’m not going to spend a lot of time on hair straighteners anymore — that’s for sure. And so then she starts to do what she wants. She starts to, you know, honor her own hair because she realizes no one was actually upset about her hair. They were upset that she was a lady, and that she was black, and that she had authority.

On the idea that intention matters

If you’re in a boardroom, a woman is not there to have you talk about her chest or how she looks. She’s there to do her job. And you are preventing her from doing her job by making something about her looks. You’re preventing her from actually having power she has worked for in the world.

On how to respond to people who think these sorts of issues don’t matter

What we need to do I think is encourage men — or those people that think our stories don’t matter — to tell their own stories. I think part of the problem, part of the reason men do this is that they have no empathy. And part of the reason they have no empathy is because they are not allowed to talk about their experience. …

I’m not saying we have to cede the ground of what has been done to us. But I really do think part of the problem is men have spent so much time thinking about their own needs that …. they cannot see other people’s stories. All they can see is: I would like to talk about breasts, not: What does it do to your co-worker to talk about breasts in the boardroom? What are you actually doing to this person who is your peer?

And the only way I can think about this — and I think this goes for race as well — is that if people can think of us as peers and not these foreign things that they get to judge, if we can tell each other our actual stories, I do think men can start to understand and perhaps change their behavior.

On the way women weaponize language, too

Oh, absolutely. Because, you know, [it] is not as if men are bad, women are good. It’s that we live in a society where we’re all sexist. … This is a hierarchical society. … We’re all living in that bubble and we all behave within it. And so we’re not trying to tear down each other. We’re not trying to, you know, tear down ourselves. What we want to do is look at the system and acknowledge what it’s doing to all of us.

Gustavo Contreras and Justine Kenin produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Beth Novey adapted it for the Web.