5 Key Facts Not Explained In White House COVID-19 Projections

BY NURITH AIZENMAN

President Trump and his top scientific advisers on the coronavirus task force gave a much-anticipated presentation Tuesday night, laying out the data behind the president’s recent shift in tone regarding the outbreak, including his decision to extend national social distancing guidelines through April 30.

Specifically, officials pointed to a computer model released weeks earlier by Imperial College London that, at the time, predicted that if no action were taken to slow the spread of the virus, about 2.2 million people in the United States would die over the course of the outbreak.

Then administration officials described separate modeling that predicts that by imposing strict social distancing measures, the toll from the current wave of infections can be reduced to somewhere between 100,000 and 240,000 deaths.

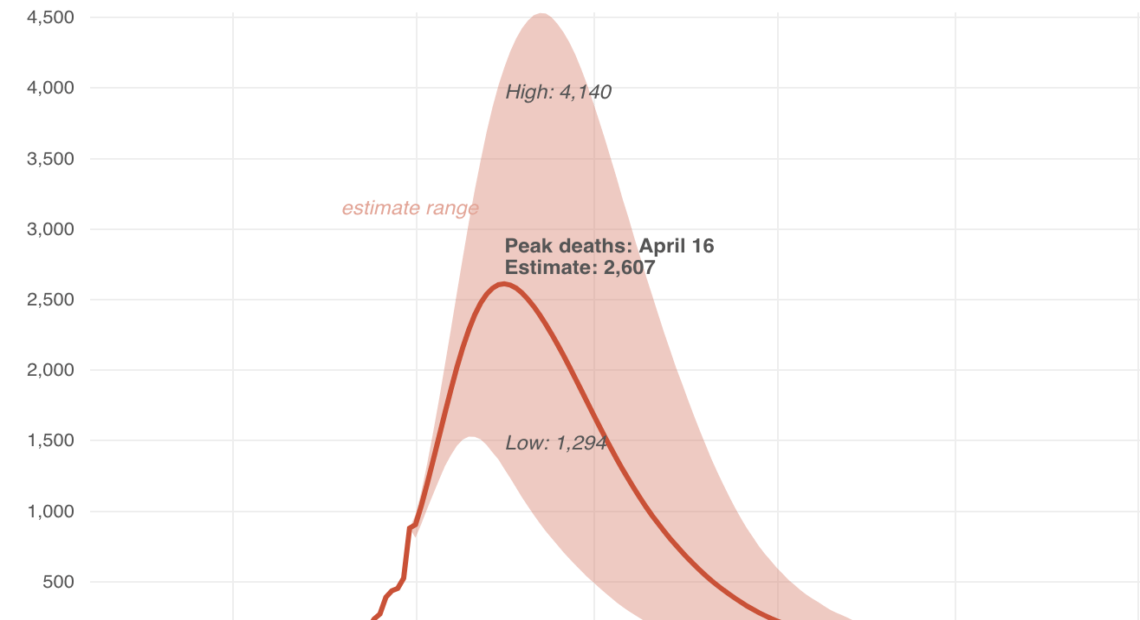

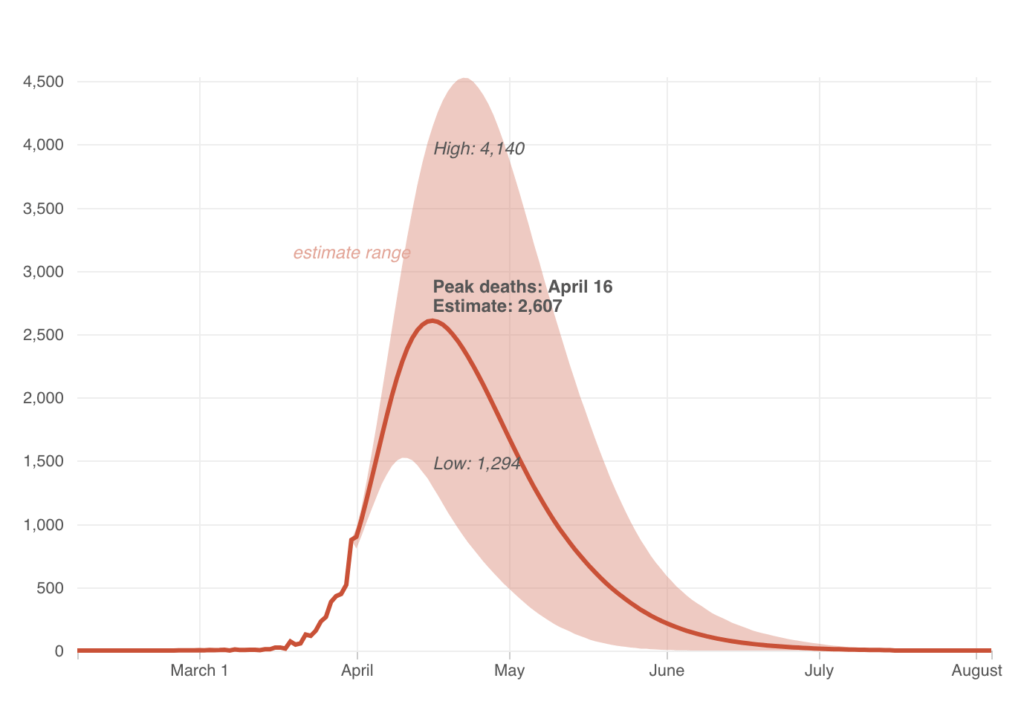

Although officials implied that this estimate was based on the administration’s own in-house modeling, they did not provide further details about those calculations. Instead, officials discussed a model from an outside group – the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, or IHME — which produced projections very similar to the administration’s findings, according to Dr. Deborah Birx, coordinator of the coronavirus task force.

NPR reached out to two researchers who helped put together IHME’s model. We learned of four assumptions made by the model that administration officials did not mention.

Here’s what those assumptions are, and why they matter.

The president’s guidelines are not what makes the difference …

IHME’s modelers say they did not take into account the impact of the president’s social distancing guidelines — first unveiled on March 16 as a 15-day plan, now extended through April 30. That’s because the president’s recommendations are not binding. And in states where governors haven’t imposed strict social distancing rules of their own, it’s not clear to what extent people are following the White House call to stay home as much as possible. The recent throng of vacationers on Florida’s beaches certainly suggests that plenty of people are not heeding the president’s guidelines

“Even if there’s a national order, we have to follow what the state is doing,” says Ali Mokdad, a professor of health metrics sciences at IHME. “People will follow the rules of their own state.”

… state action is what matters

IHME’s model forecasts the outcome for each state by taking into account not just which measures state officials have imposed, but also the date on which officials imposed the measures and how much transmission was already underway by that point, as measured by the number of COVID-19 deaths. The model also considers how strict the measures are, with the greatest weight given to states that have imposed all three of the following options: closing educational facilities, closing nonessential businesses and issuing stay-at-home orders. The model is then adjusted based on what portion of a state’s residents those various rules have been applied to. For instance, are the measures limited to certain cities or counties? Or are they statewide rules?

Governors that haven’t issued statewide social distancing rules will do so in a week.

A number of governors haven’t issued any of the strict social distancing rules the model takes into account. Other governors have only issued such rules for select areas of their state.

IHME’s model assumes that seven days from now, all states that haven’t already done so will impose the full range of social distancing rules statewide.

States will keep the social distancing rules in place through June 1

By contrast, Trump’s presidential guidelines only apply through April 30. The president has indicated that he may extend that date as the situation warrants.

But at the briefing Tuesday, officials did not specify how long their modeling assumes social distancing measures would remain in place. Chris Murray, IHME’s director, says the modeling team is working on a projection for exactly “what sort of rebound we will see,” if social distancing was eased after April 30 instead of June 1. But he says there’s no question it would be significant.

If and when the current wave of infections is suppressed, the U.S. will remain vulnerable.

Technically this is not an assumption in the model, but a prediction: Notwithstanding the large number of people who will get sick and even die over the roughly three months the model projects it will take to snuff the current wave of infections, the vast majority of Americans will not contract the virus. This means they will not have immunity against future waves of infection, which could be sparked by cases in the U.S. that remained undetected or by infected visitors from countries where the virus is still circulating widely.

“Our rough guess is that come June, at least 95% of the U.S. will still be susceptible,” says IHME’s Murray. “That means, of course, it can come right back. And so then we really need to have a robust strategy in place to not have a second wave.”