It’s Not Just Nursing Homes: Threat Of Coronavirus Spread Looms In Other Communal Settings

READ ON

When COVID-19 got a toehold at Life Care Center of Kirkland, the results were devastating. Thirty-five residents from that one facility died, accounting for roughly half the deaths from the aggressive virus in Washington.

But it’s not just nursing homes and assisted living facilities, with their older and sicker populations, that are at heightened risk for a coronavirus outbreak. Any communal facility where a group of people are living, eating and sleeping together – from homeless shelters to group homes to jails and prisons to state mental hospitals – is a potential breeding ground for the virus.

One of the biggest dangers is that staff will bring the virus into a facility, where it will then spread rapidly, as happened at Life Care Center, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Already, three staff members at the Washington Department of Corrections (DOC) have tested positive for COVID-19: one at the Monroe Correctional Complex, another at agency headquarters in Tumwater and the third, announced Wednesday, at a work release facility in Port Orchard. So far, DOC said, no inmates have tested positive, although two units at the Monroe prison are in partial-quarantine.

On Thursday, the Washington Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) announced one of its staff members at Western State Hospital has tested positive for COVID-19. However, the staff member had not been at work since March 8 and is not believed to have come in contact with other staff or patients during the incubation period of the virus.

That announcement came just hours after DSHS confirmed the first case of COVID-19 in a patient at the sprawling psychiatric facility in Pierce County.

That patient is now being treated at an area hospital and is expected to recover. Meanwhile, DSHS said it’s working with the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department to initiate “contact tracing” to see who might have come in close contact with the patient. The agency says it also plans multiple daily screenings of patients who were on the same ward as the infected patient and will restrict the movement of patients and staff between wards.

“We work in a very challenging environment and we’re trying to keep our staff safe and our patients safe and our visitors safe,” said Dr. Brian Waiblinger, DSHS’s chief medical officer, in an interview just hours before the first case was announced.

The best available science suggests that people should maintain at least six feet of distance from others to avoid contracting COVID-19 – which is believed to be spread through droplets. But practicing safe distancing is often a challenge in congregate living settings.

For instance, at Western State Hospital, many of the buildings are more than 100-years-old and feature long, eight-foot wide hallways. Even before the first case of COVID-19 there, efforts were underway to limit traffic in the narrow halls and spread people out. Patients are also being educated on hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette and social distancing.

“Social distancing is a challenge, but the messaging is getting out there so patients are actually talking about social distancing, it’s interesting how the vocabulary has changed,” Waiblinger said.

But with a complex patient population, it’s a message that has to be repeated and reinforced frequently.

In an effort to keep coronavirus out of its facilities, DSHS has restricted visitor access to 11 congregate facilities it operates, including the state psychiatric hospitals and the Special Commitment Center for sex offenders on McNeil Island, as well as at 67 state-run homes for the developmentally disabled.

Sean Murphy, the assistant secretary for behavioral health at DSHS, called coronavirus “probably one of the most unique medical challenges that we’ll face in our careers.” But he and Dr. Waiblinger also noted that DSHS facilities have well-established infection control protocols because of other diseases like influenza.

“We use the same techniques to manage influenza that you do in managing a contagion like COVID,” Waiblinger explained.

Of course, COVID-19 appears to be more contagious than the flu and there’s no vaccine which raises the stakes and the danger – not just for patients and residents, but for front line staff.

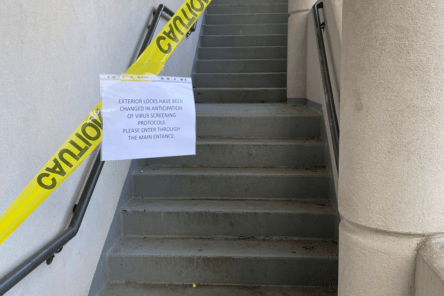

At Western State Hospital, entrances have been blocked off and locks changed to prevent employees from entering without being screened first for coronavirus symptoms. Courtesy of Western State Hospital employee

“Some of the real unsung heroes in the business are the folks that are working the front lines for direct care,” Murphy said.

Tensions, though, appear to be mounting between management and the union workforce at Western State Hospital which serves 757 patients and has more than 2,500 staff.

Maria Claudio is a psychiatric social worker at the hospital and union shop steward with the Washington Federation of State Employees (WFSE). In an interview, Claudio disputed the agency’s assertion that staff on the ward where the infected patient was housed were having their movements restricted. On Thursday, the day after the patient tested positive, Claudio said two staff from that ward were redeployed to other wards.

“It’s not true that they’re stopping staff members from that ward from going to other wards – that is not true,” said Claudio.

In response, a DSHS spokesperson, Kelly Von Holtz, said DSHS is trying not to float staff from the ward where the patient tested positive to other wards “as much as possible.”

Claudio also complained that Western State Hospital has not yet begun screening all employees for symptoms of coronavirus as they arrive for work.

“We’re the epicenter, other places have already started weeks ago screening, why haven’t we,” Claudio asked. “It’s not happening. And it’s too late.”

Von Holtz said the hospital was waiting for a shipment of thermometers to arrive and that entrance screening is expected to begin at 6 p.m. on Thursday.

The president of WFSE, Mike Yestramski, said his union is asking DSHS to immediately implement coronavirus screening for all staff, suspend all non-emergent transportation of patients and halt admissions to the hospital for 14 days, as well as prioritize COVID-19 testing for front line staff.

“Right now we are in a crisis situation and this is a time when people are looking to leadership to stand up and lead and that I think has been the biggest concern to me,” Yestramski said.

DSHS also operates four Residential Habilitation Centers (RHCs) that serve more than 600 developmentally disabled clients, including the Rainier School in Pierce County and Yakima Valley School in Selah. As in nursing homes, caring for the developmentally disabled often involves close proximity as caregivers dress, bathe, feed and help their clients use the bathroom.

In normal times, this intimate work is challenging. In the age of coronavirus, it’s potentially dangerous.

“We’re all nervous,” said Julianne Moore, a WFSE union shop steward who works in the physical therapy department at the Yakima Valley School. “Everybody’s scared, I think.”

But Moore praised the dedication of the staff at Yakima Valley School and said her union and management are working well together to implement additional safety measures. Those include taking the temperatures of clients at least twice a day, screening employees coming to work and wearing additional protective equipment when it’s deemed necessary.

“We are using every precaution we can to not pass the virus to our residents because they are much more vulnerable than we are,” Moore said.

Of particular concern, is the potential for COVID-19 to spread through jails and prisons which are often overcrowded and whose populations frequently have underlying health conditions that put them at higher risk for complications from the virus.

Dr. Marc Stern, an Olympia-based correctional healthcare consultant and former assistant secretary for health care at the Washington Department of Corrections, is advising the National Sheriffs Association on coronavirus and has been on several national conference calls since the outbreak began. His message to anyone who will listen is that correctional facilities should be reducing their densities now to reduce the risk of a serious outbreak.

“What I’ve been saying, and I will continue to say, is I think we need to be thinking around the country of downsizing our jails, prisons and detention centers,” said Stern who also teaches in the University of Washington School of Public Health.

Dr. Stern warned that jails and prisons – which he likened to nursing homes and cruise ships — face two potential crises.

One is an outbreak of coronavirus that spreads rapidly through the inmate population and results in many individuals being hospitalized with complications – putting further strain on the community-based medical system.

The second, longer-term risk, he said, is that correctional staff will get sick and no longer be able to report for their shifts.

“We may run into a situation where our jails and prisons are short-staffed and when that day comes, we should be prepared to deal with it by population control,” said Stern, who expects the CDC to issue guidance to correctional facilities in the coming days.

Dr. Stern said early release decisions are best made at the state and local level, but urged consideration of furloughs, suspended sentences and home monitoring for medically-vulnerable inmates and those nearing their release date.

On Thursday, more than 160 organizations and individuals, including two Democratic state lawmakers, sent Gov. Jay Inslee and DOC Secretary Steve Sinclair a letter requesting a number of actions to address the risk of COVID-19 in the prisons, including the immediate “compassionate release” of 51 inmates who are more than 80 years old, a group the letter writers said is disproportionately African American. The letter also called for a process of “immediate review” for inmates 70 years old and older and those with serious, underlying health issues, with the presumption that they would be released too.

This follows a letter sent Monday to Inslee and Sinclair from Disability Rights Washington and other advocacy groups urging the release of older inmates and inmates with less than six months to go on their sentences to reduce the risk of the spread of coronavirus.

“Part of our effort here is to reduce the population so DOC has some flexibility in trying to socially-distance within the prisons, so they have some flexibility to move people onto units who can be quarantined together, or to reserve units for people who start showing symptoms,” said Rachael Seevers, an attorney with Disability Rights Washington.

As of December, Washington’s 12 prisons held nearly 17,000 people and were at 100.3 percent of capacity.

For its part, Inslee’s office said there are a lot of things to consider before making any decisions that would affect the prison population and that nothing has been decided.

Also Monday, the ACLU of Washington and other immigrant rights groups sued U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement seeking the release of detainees as the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma who are “at high risk for serious illness or death in the event of COVID-19 infection.”

As for city and county jails, Seevers, of Disability Rights Washington, said the goal should be to “stop the front door” – meaning limit new bookings.

Already jails across the country are taking steps to reduce their populations, including a couple of county jails in Washington and Oregon that have started releasing some inmates.

In Spokane County, where overcrowding is an ongoing issue, The Bail Project, which provides free bail assistance, sent a letter to city and county officials last week warning of the potential for a “swift and deadly” outbreak of COVID-19 and calling for steps to reduce the jail population.

But John McGrath, the former director of the Spokane jail who is now the jails liaison for the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs, offered an alternative perspective, noting that Washington jails typically don’t house low-level offenders and none have reported a confirmed case of COVID-19 to date.

“The jails don’t have anybody at the time, so I don’t see the need to release people into the community where there is a virus,” McGrath said.

Instead, McGrath said, jails are focused on sharing information with each other in weekly conference calls, which have also included Dr. Stern. In addition, in the spirit of open-source sharing, a new website was created for jails directors to post their policies and best practices for combatting coronavirus. McGrath said Washington jails are also sanitizing more, changing their visitation policies and many are screening staff and inmates for signs of COVID-19.

“I think they’re as prepared as they can be,” McGrath said. “Could it happen, it could obviously.”

Related Stories:

COVID-19, 5 years later: Reflections on the scars we carry, and resilience in unprecedented times

NWPB caught up with local residents and doctors to talk about how they’ve moved forward following the COVID-19 pandemic. They spoke about how the experience changed them and wisdom they’ve gleaned along the way. These are their reflections.

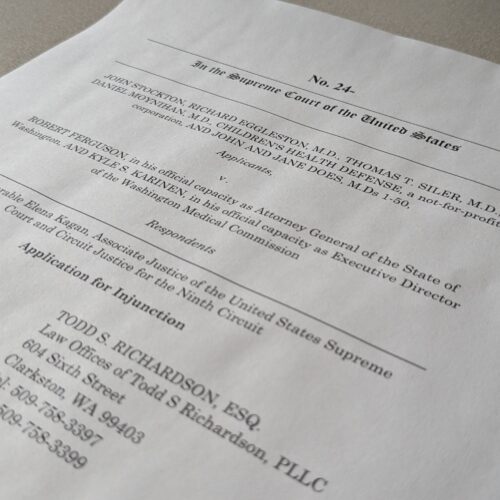

US Supreme Court will consider petition for stay in COVID-19 free speech case

The U.S. Supreme Court will review an application for a stay in a federal lawsuit involving local retired eye doctor Richard Eggleston.

Group representing retired Clarkston ophthalmologist asks US Supreme Court for injunctive relief

A retired Clarkston eye doctor is part of a group asking the U-S Supreme Court to grant an injunction in a lawsuit against Washington state officials.