McCoy Tyner, Groundbreaking Jazz Pianist With Deep Resonance And Hammering Attack, Dies At 81

BY NATE CHINEN

McCoy Tyner, a pianist whose deep resonance, hammering attack and sublime harmonic invention made him a game-changing catalyst in jazz and beyond, died Friday, March 6, at his home in New Jersey. His death was confirmed by his manager. No cause of death was given. He was 81.

Tyner was the last surviving member of the John Coltrane Quartet, among the most momentous groups in jazz history. Few musicians have ever exerted as much influence as a sideman. His crucial role in the group’s articulation of modal harmony, from the early 1960s on, will always stand as a defining achievement: The ringing intervals in his left hand, often perfect fourths or fifths, became the cornerstone of a style that endures today.

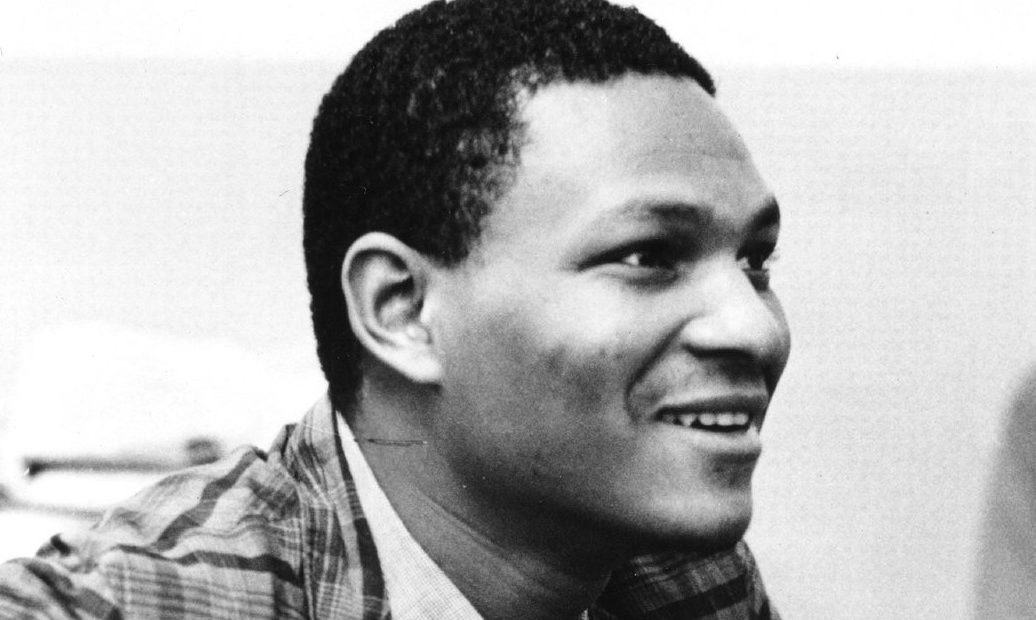

Jazz great McCoy Tyner, seen here in a 1970 photo, died Friday at the age of 81.

CREDIT: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

But Tyner was always a more multidimensional musician than the sum of his mannerisms would seem to suggest. And he had a long, consequential post-Coltrane career as a composer and bandleader. Among his dozens of albums are a handful regarded as classics, like Reaching Fourth, The Real McCoy and Atlantis. A number of his compositions, including “Passion Dance” and “Peresina,” have entered the common repertory.

“On all the recordings with Coltrane, and indeed on all his work of the ’60s, McCoy’s crisp, lightning-fast right-hand lines, set against the sheer power of his left, are a revelation,” jazz historian Lewis Porter, one of Coltrane’s biographers, wrote in an email to NPR Music on Friday. “He came out of the tradition (he mentioned Thelonious Monk as one of his favorites), but he was one of those few who forged an absolutely unique style.”

Because Tyner’s work with Coltrane catapulted him to the first tier of accompanists, that style can be heard on some of the landmark jazz albums of the ’60s. Among them are Page One, by tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson, and Open Sesame, by trumpeter Freddie Hubbard – a pair of auspicious debuts on Blue Note — and Stick-Up! by vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson.

Tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter enlisted Tyner on a close succession of Blue Note sessions in the mid-’60s. One of these yielded the classic JuJu, which also had Elvin Jones on drums and another Coltrane associate, Reggie Workman, on bass. The title track to JuJu, which opens the album, bears Tyner’s stamp from the first downbeat, with a cresting wave of chords in a shrewdly indeterminate key.

Alfred McCoy Tyner was born Dec. 11, 1938 in Philadelphia, the oldest child of Jarvis Tyner and the former Beatrice Stevenson. The oldest of three siblings, he began taking piano lessons at 13. His mother, who ran a beauty salon out of their West Philadelphia home, installed a piano there, because it was the largest room of the house.

This yielded unanticipated benefits, as Tyner recalled in a 1963 interview with Stanley Dance, in DownBeat magazine. “Bud Powell and his brother were living just around the corner from me in Philadelphia,” he said, referring to the pacesetting bebop pianist, “but they didn’t have a piano in their apartment, and Bud came to my mother’s house to play.” Powell — who, with peers like Charlie Parker and Max Roach, had redefined the language of modern jazz in the 1940s — remained a core influence for Tyner, even as he developed his own unmistakable voice.

Tyner studied classical theory and harmony at the Granoff School of Music, but also drew formative insights from personal instruction — including conga lessons with Garvin Masseux, who was working at the time with Nigerian drummer Babatunde Olatunji.

By his high school years, Tyner was playing professionally in and around Philadelphia, as part of a modern jazz scene that was one of the most vibrant in the country. Among his more fateful appointments was a band led by trumpeter-composer Cal Massey, an associate of Coltrane; it was also through Massey that Tyner met his future wife, Aisha, whose sister was a vocalist in the band.

In 1959, Tyner joined trumpeter Art Farmer and saxophonist Benny Golson in a group they called The Jazztet; he made his recording debut on Meet the Jazztet, released the following year. That same year, 1960, Tyner played on Coltrane’s album My Favorite Things; his tolling, meditative chords on the title track, a popular song borrowed from the hit Broadway musical The Sound of Music, were a key part of its allure.

The classic John Coltrane Quartet — with Tyner, Jimmy Garrison on bass and Elvin Jones on drums — formally coalesced in 1962. For the next several years it created at a prodigious pace, recording landmark albums like Crescent and A Love Supreme, and setting a fearsome bar for intensity on the bandstand. Recordings like Live at Birdland have been prized by generations of musicians and fans; in 2005 another live document, Live at the Half Note: One Down, One Up, left another major impression, 40 years after its recording date.

Tyner stayed with Coltrane until soon after that recording, as the music grew more cacophonous, rhythmically abstract and untethered from root tonality. His piano chair was passed on to Alice Coltrane, who quickly made it her own.

“I was so immersed in the music when I was with John,” Tyner told me in 1997. “The influence was so great, and the roles we all played in that group were so powerful; you couldn’t divorce yourself from it just because you weren’t physically there. For a while there, all the horn players that were with me wanted to sound like John. So I deliberately started using alto sax instead of tenor, and other instruments, because I wanted to kind of try something different.”

The scale of Tyner’s output ranged from solo piano to big band, with some notable midsize efforts like the seven-piece band on Expansions, which enlisted Ron Carter on cello and Shorter on clarinet as well as saxophone. A similarly titled follow-up, Extensions, included Alice Coltrane’s harp; Sahara, which followed, found Tyner experimenting on koto and flute.

The searching Afrocentrism of these albums carried on the intrepid tone and earnest spiritualism of Coltrane’s music, without overt emulation. The critic Gary Giddins, reflecting on the 1970s in The Village Voice, once pegged Tyner “the most influential pianist of the decade,” an assessment that could credibly be extended outside that frame. As he settled into the stature of an elder, Tyner worked meaningfully not only with peers like Hutcherson and alto saxophonist Gary Bartz, but also figures from successive generations, like saxophonists Michael Brecker and Joe Lovano.

Tyner was a 2002 NEA Jazz Master and a five-time Grammy winner — most recently in 2004 for his album Illuminations, featuring a band with Bartz, trumpeter Terence Blanchard, bassist Christian McBride and drummer Lewis Nash. He worked extensively in a trio format; one longtime working band had Avery Sharpe on bass and Aaron Scott on drums. Tyner’s final album was a piano recital, Solo: Live From San Francisco, released in 2009; it includes compositions by Coltrane and Duke Ellington as well as his own songs, including “Ballad For Aisha.”

In addition to Aisha, Tyner’s immediate survivors include his son, Nurudeen; his brother, Jarvis; his sister, Gwendolyn-Yvette Tyner; and three grandchildren.

The legacy of Tyner’s pianism can be heard far and wide, in the music of everyone from salsa legend Eddie Palmieri to Late Show bandleader Jon Batiste. His innovations in harmony, with their intimations of transcendence, form a standard proudly upheld by contemporary pianists like Nduduzo Makhathini, whose forthcoming Blue Note debut bears the influence unmistakably.

“I feel very honored, actually,” Tyner told me about the legions of pianists who have emulated his style. “I really do, because I think that if I could make a statement that makes a difference, and the influence could be preserved through the generations to come, that means that my stay here on earth has a meaning.”