‘We Won’t Build It’: Northwest Tech Workers Struggle With Company Ties To Immigration Enforcement

Listen

BY ESMY JIMENEZ / KUOW

The Southern border may be far from Washington state, but software used by immigration officials is built in Seattle.

Now tech workers are grappling with their responsibility as the creators of that technology. Some have become unlikely activists.

James Baker is one of thousands of tech workers in Seattle.

He got his first taste for computer science as a bored high schooler, where he played games on his graphing calculator in math class.

Now he works at Tableau, a data visualization company, as a principal technical advisor. He’s been there for over a decade.

But most recently he found tension building between his work and its connection to immigration.

Tableau has had contracts with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security since 2012. Baker isn’t allowed to talk about the contracts because of confidentiality agreements he signed. But some of that information is publicly available.

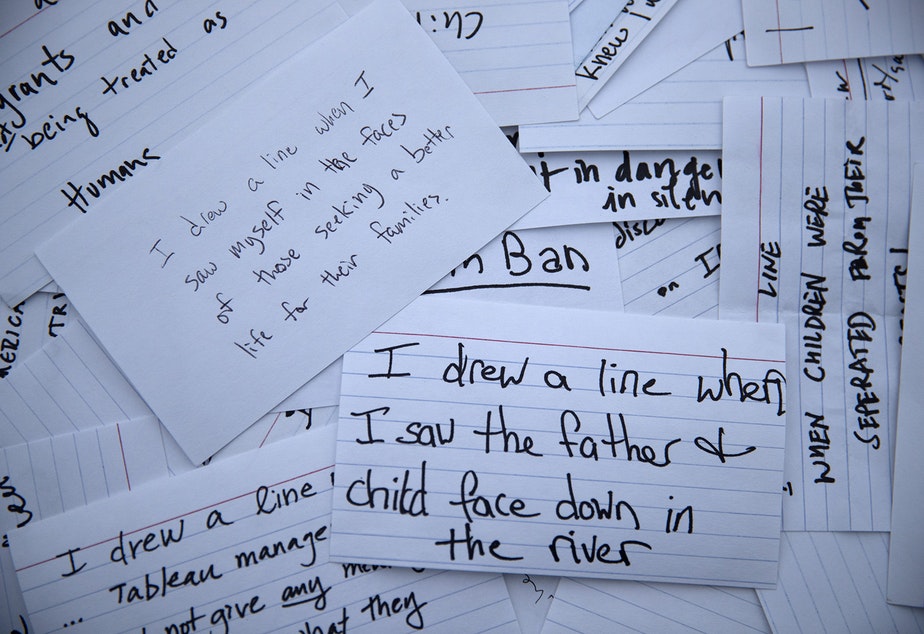

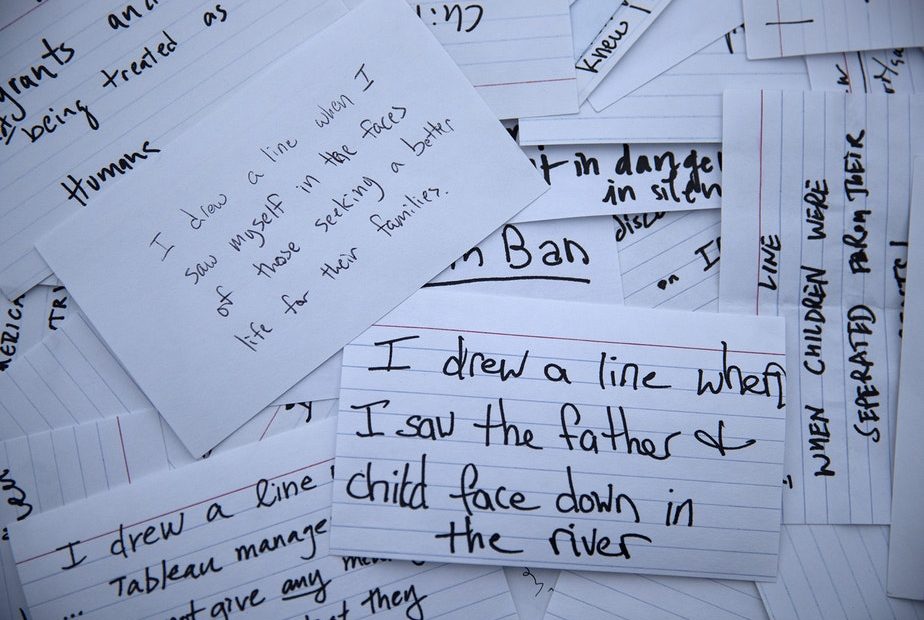

“I drew a line when I did see those pictures of extreme overcrowding and folks jammed in those rooms and just the conditions, the cages,” Baker said.

This fall, Baker led 200 employees in a rally calling out Tableau. They want senior leadership to create a human rights policy that would set a precedent for who the company does business with.

James Baker wears a ‘Drawing A Line’ pin on Wednesday, December 4, 2019, in Seattle. CREDIT: Megan Farmer/KUOW

There are 40 unique contracts between Tableau affiliates and two main immigration agencies (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection), according to federal data. These contracts total $1.5 million.

Immigration enforcement is not Tableau’s largest client, but the U.S. Department of Homeland Security is still among their top 10.

A lot of these contracts go through a network of partners and resellers.

It’s like if you bought Microsoft Office at Target or Wal-Mart. Those stores are licensed to sell Microsoft software. Resellers like Target will bundle services and sell that package. They get a percentage of that purchase, as does Microsoft, which owns the software license.

For example, Tableau partners with a company called Westwind LLP, which provides Tableau software and services to border patrol and ICE. It’s unclear what information they illustrate using Tableau.

In an emailed statement, a Westwind spokesperson would not say what services they provide the feds.

“Westwind is often asked to provide technology products and services for projects that are not disclosed to us,” he wrote.

Tableau, likewise, would not comment beyond this statement: “We deeply care about the human side of these complex issues. Core to our values, Tableau has a long history of using data to actively engage to address social problems … we respect diverse thought and open dialogue.”

Salesforce, the company that bought Tableau for $15 billion last summer, also stayed quiet.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security, too, would not say how it uses Tableau.

Employees at Microsoft (Redmond, Wash.), Amazon (Seattle), and Github (San Francisco) are also staging rallies or circulating internal letters calling on company leadership to end contracts with ICE and CBP — or at the very least, develop a human rights resolution to build ethics into the business pipeline.

Some tech workers aren’t waiting on internal change, however.

Moment Of Reckoning

This fall, Chef, a small tech company based in Seattle, had a moment of reckoning. A former employee discovered part of his code was being used by ICE. So he deleted it in protest.

Barry Crist, the CEO of Chef, was firm that Chef would continue working with ICE, whether or not the company personally agreed with the agency’s policies. But over a weekend in September, company leadership changed their stance and ultimately opted to sunset contracts with ICE.

Tech workers took notice.

“I really, really am intrigued to know what happened there,” said Raif Majeed, a Tableau engineer. “It gives me hope that companies will come around and do the right thing.”

Employees such at those at Tableau or Chef are not alone in the tech industry. A “We Won’t Build It” presence has grown online, with tech workers discussing the issue under the hashtag #WeWon’tBuildIt. One Twitter account “Amazonians: We Won’t Build It” focuses on “Amazon workers calling for accountability and transparency in the tech we build.”

Over 200 tech workers from Tableau staged a rally outside of company headquarters in Seattle on October 2019. Courtesy of Tableau Tech Employee Ethics Alliance

Amazon employees have also circulated petitions asking the company to cut ties with ICE.

Companies like Microsoft have also gotten involved and openly support DACA legislation that provides young, undocumented immigrants with work permits, for example.

It’s a movement that has been building slowly but steadily, said Irina Raicu, the director of internet ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University.

“The slogan of the ’60s, when we used to say that the ‘personal is political’ and building on that, this generation seems to be taking up the cry like the ‘professional is the political’,” Raicu said.

Inspired To Think Big

Tech workers have been inspired by company leadership to innovate and think big. If a past tech motto was to “move fast and break things,” now employees are breaking things from the inside. Increasingly, conversations on how to incorporate ethics at all levels of technology production are taking center stage.

“Technology workers have a lot more power than other workers do in many other industries,” Raicu said.

With a specialized skill set, they are in high demand, and can leverage themselves and push their companies.

“The companies will have to be prepared for an even more empowered kind of workforce who actually understands even better the fact that that some of this responsibility is on them and they want to play a role in guiding how those decisions are made,” Raicu said.

Not everyone in tech feels so certain.

Some employees at major companies like Google and Github have already left their jobs in protest.

Most of the Tableau workers interviewed for this story struggled with that question. Majeed said it would be hard to stay, another said it would wear them down to stay at a company whose ethics they disagree with, but it might be hard to find another job as good as this one.

Baker, one of the lead organizers was quick to answer: “I certainly could find myself leaving.”

“We’ve been asked if we can disagree and commit and move on and accept the company’s response, and our answer is no, we can’t commit to that,” Baker said. “This is where we start to go into uncharted waters in terms of corporate America.”

Do you work in tech in Seattle? Are you protesting against your company’s actions? We’d love to hear from you. Using a non-work phone or computer, reach out to Esmy Jimenez securely on Signal on +206 565 7902 or email esmy@kuow.org. You can also send us snail mail or use our SecureDrop: hcxmf67v3ltykmww.onion

Copyright 2020 KUOW. To see more, visit kuow.org

Related Stories:

Immigration enforcement concerns cause mixed attendance trends in North Central WA schools

Eastmont Junior High School students make their way past the 800 wing on the way to their second period in East Wenatchee. (Credit: Jacob Ford / Wenatchee World) Listen (Runtime

These churches offer shelter and sanctuary to vulnerable migrants. Here’s why

Bishop Joseph Tyson (left) and the Rev. Jesús Mariscal (right) of the Yakima Diocese worry about how their parishioners will cope with broad changes to immigration policy, which have had

Lawsuits draw attention to role of local authorities in enforcing federal immigration policy

Two lawsuits against the Adams County Sheriff’s Office have drawn attention to the role of state and local authorities in enforcing federal immigration laws.