Remembering Neil Peart, A Monster Drummer With A Poet’s Heart

BY ANNIE ZALESKI

When Canadian prog-rock innovators Rush were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2013, it was both somewhat surprising and totally appropriate that drummer Neil Peart opened the trio’s acceptance speech. The musician and author, who passed away at the age of 67 on January 7 after a private, three-and-a-half-year struggle with brain cancer, famously eschewed the spotlight and rarely gave interviews. However, the Ontario native was a quiet leader who shaped Rush’s voice, writing the bulk of the band’s lyrics and maintaining a steely, rock-solid presence behind the drumkit.

“There’s a stereotype about rock music, that it’s mundane or predictable. Neil’s lyrics were neither. … [He] had the ability to express complicated ideas in a rock song,” Donna Halper, an associate professor of media studies at Lesley University, tells NPR Music. A media historian and former broadcaster, Halper is credited with getting Rush their U.S. record deal and breaking the band: In 1974, while working as music director and a DJ at the legendary Cleveland radio station WMMS, she spun an import copy of Rush’s early single, “Working Man,” which promptly took off.

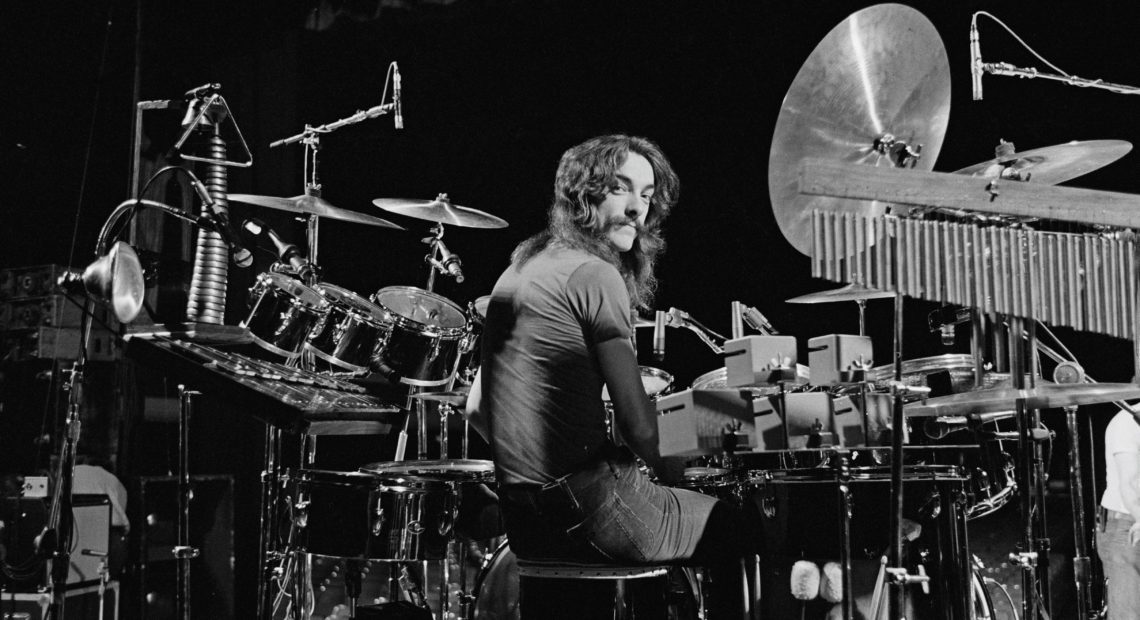

Neil Peart, of Rush, photographed in Cleveland on Dec. 17, 1977. The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductee died Jan. 7, aged 67.

CREDIT: Fin Costello/Redferns

Peart didn’t play on the studio version of “Working Man,” but joined Rush that same year, replacing original drummer John Rutsey. Peart contributed his first lyrics to the band’s 1975 LP, Fly By Night and, from there until Rush’s final studio album, 2012’s Clockwork Angels, he became known for his philosophical musings on road life and restless souls; sharp critiques of power and greed; fantasy-tinged vignettes; and incisive political and social commentary, cloaked in metaphor.

Peart’s love of literature and reverence for history deeply informed his songwriting. “Red Sector A,” for example, emerged after he read accounts of World War II concentration camp survivors. “Manhattan Project” addresses the U.S. dropping atomic bombs on Japan in 1945, from multiple viewpoints. For much of Rush’s career, Peart was also dogged by long-ago praise for the author Ayn Rand, whose works were an influence on the sprawling 1976 song cycle 2112. (He later clarified that Rand’s work no longer resonated with him.) In a 2015 Rolling Stone cover story, Peart self-described as a “bleeding-heart libertarian.”

That streak of individuality is also there in his songwriting, making Rush’s lyrics feel more like a manual for life, full of economical quips (“I’m so full of what is right / I can’t see what is good,” from “The Color of Right”) and thorny questions (“Roll The Bones” and its skepticism about faith). Like the best songwriting, Peart’s body of work was also malleable enough to grow with its listeners — his songs often mused about aging and the importance of dreaming; the ominous “Subdivisions” railed against the conformist suburbs that “have no charms to soothe the restless dreams of youth.”

Peart’s lyrical vulnerability also helped Rush’s music resonate across generations. Even as a young man, Peart thought deeply about the future and how fleeting life could be; the facetious 1975 song “I Think I’m Going Bald” references going “grey my way.” The fan-favorite 1987 single “Time Stand Still,” which features Aimee Mann on background vocals, is an ode to being present (“Freeze this moment a little bit longer / Make each sensation a little bit stronger”) that’s shaded with melancholy, because the protagonist knows that the other shoe can drop at any time. “Experience slips away / The innocence slips away.” Four years later, on 1991’s “Dreamline,” his thoughts crystallized into a bittersweet observation: “We’re only immortal for a limited time.”

“Writing lyrics, like drumming, was something he took seriously and respectfully,” Halper says. “He made observations that the average fan could relate to, and he encouraged people to think for themselves, and to be themselves, too — to stand up for what they believed.

“And, above all, his lyrics made people think — Rush fans were liberal, conservative, religious, non-religious — but they all united around their respect for the band and their admiration for how Neil could articulate their experiences, or give them a new way to look at an issue.”

In no small part because of his erudition, Peart’s erudition earned him the nickname “The Professor.” It was apt: Carrying himself with an air of well-spoken authority, he possessed knowledge about a variety of topics, owing to his extensive global travels — on Rush tours, he was known for taking off on bicycle rides and, later, would hop on his motorcycle to travel between gigs — and a voracious curiosity about the world around him. In his 2002 book, Ghost Rider: Travels on the Healing Road, he described going to art museums in the afternoons before Rush concerts “to feed my growing interest in paintings, art history, and African carvings.”

While an interesting travelogue, at its root Ghost Rider was a chronicle of how to repair a shattered self. The book details how Peart embarked on a solo motorcycle trek “to try to figure out what kind of person I was going to be, and what kind of world I was going to live in” after his 19-year-old daughter, Selena, died in a 1997 car crash, and his wife Jackie passed due to cancer the following year.

All told, Peart released seven nonfiction books, several fiction collaborations and poured out thousands more words via his personal website. “What made Neil such a good writer is how much he loved to read,” Halper says. “He really loved and respected books. He loved good literature — he and I sat around one night talking Shakespeare — he loved poetry, he loved philosophy. He valued good conversation. He was a thinker — in the truest sense of the word.”

This mindset also made Peart a laser-sharp analyst of music. In a 1986 Modern Drummer interview, he discussed the virtues of Thomas Dolby and Peter Gabriel, and how they incorporated electronics into their work, and mused on the “new morality that has to be developed for sampling.” A2017 tribute to drumming hero Buddy Rich, meanwhile, found Peart describing the late jazz icon as having the “ears of a dancer.”

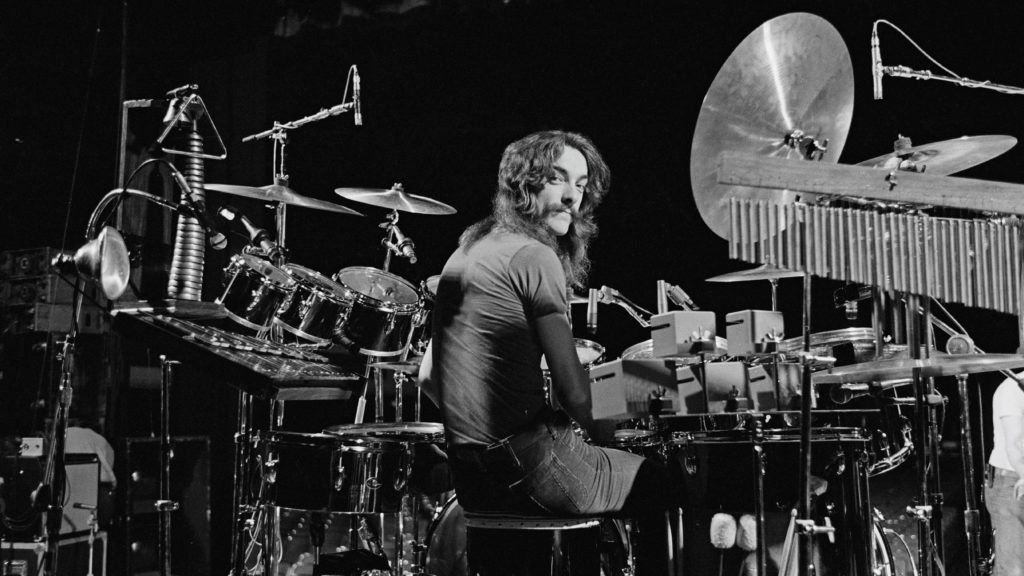

Neil Peart, photographed in his natural habitat on April 3, 2011 in Nashville. CREDIT: Frederick Breedon IV/WireImage

Peart was an ardent admirer of ferocious, aggressive drumming greats such as The Who’s Keith Moon and Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham, and absorbed influences from a wide range of players besides, as he relayed in a 2003 interview: Gene Krupa, Yes’ Bill Bruford, King Crimson’s Michael Giles, an obscure English session drummer named Harold Fisher. His own playing — which he honed and refined via drum lessons for as long as Rush toured — covered vast ground, darting in and out of jazz, rock, blues, funk and all points between and beyond.

Despite an iconoclastic nature, Peart found musical, and personal, brotherhood with bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson. The trio’s bond came alive during performances, which were immersive musical marathons that doubled as communal, spiritual experiences. Shows — of course — featured an extended Peart drum solo, performed with the precision of a surgeon and the creative freedom of a surrealist. But while highly technical, Peart’s playing was always joyous: As any Rush fan will share, air-drumming to 1981’s “Tom Sawyer” can be one of life’s greatest pleasures.

Peart’s peers saw him as an oracle of advice and support — as Metallica’s Lars Ulrich and E Street Band’s Max Weinberg shared in touching posthumous remembrances — as did fans: Peart was known for sending handwritten (and, later, typed) postcards to people who wrote asking him about drum techniques, musical or career advice, or the eclectic pre-concert playlists he curated for Rush tours.

On Friday, rapper Chuck D — also inducted into the Rock Hall in 2013, as part of Public Enemy — tweeted that he and Peart ended up alone together after the ceremony “talking and laughing low in relief the long night was over — a small table backstage sharing a unique moment without much word[s].”

Such a low-key moment embodied Peart’s preferred state.

“He was in many ways like an outsider — the guy who was often different from everyone else,” Halper says. “But that was okay with him. He didn’t want to be like everyone else. He just wanted to be Neil. He loved being a rock drummer, but he also loved literature. He loved poetry. He loved the outdoors. He didn’t care what society thought a rock star was ‘supposed to be’ — he wasn’t afraid to be himself, and he didn’t really care about fame. He just wanted to be good at what he did — and he was! — and he just wanted to share his music with the fans.”

Peart indeed made sure to credit the support of loyal Rush fans during his heartfelt and funny Rock Hall remarks. In addition to praising Rush’s crew, the band’s long-time manager Ray Danniels, and his bandmates, he drew laughter by noting previous inductees were like a “constellation of stars” and dryly noted that “among them, we are one tiny point of light, shaped like a maple leaf.”

But he also talked about the grounding influence of family, and shared a favorite quote from Bob Dylan, taken from a 1978 Rolling Stone interview: “The highest purpose of art is to inspire. What else can you do for anyone but inspire them?”

After Rush wrapped up their 40th-anniversary R40 Tour in 2015 and effectively called it a day, Peart retreated from the spotlight, noting in a late 2015 Drumhead interview that his then 6-year-old daughter, Olivia, “has been introducing me to new friends at school as ‘my dad — he’s a retired drummer.’ True to say — funny to hear.”