Disabled Woman Received Vinegar Instead Of Colonoscopy Prep. Secrecy Shrouds Her Death

Listen

Just before 3 a.m. on Feb. 27, 2019, an overnight caregiver woke up Marion Wilson, a developmentally disabled 64-year-old, so that she could be given a second round of colonoscopy prep medication.

Wilson, who relied on a wheelchair and was said to have the intellectual capabilities of a five-year-old, was scheduled to have the procedure later that same morning. After escorting Wilson to the bathroom, a second caregiver went to the kitchen to retrieve the remaining half gallon of bowel prep that Wilson was supposed to consume prior to the procedure.

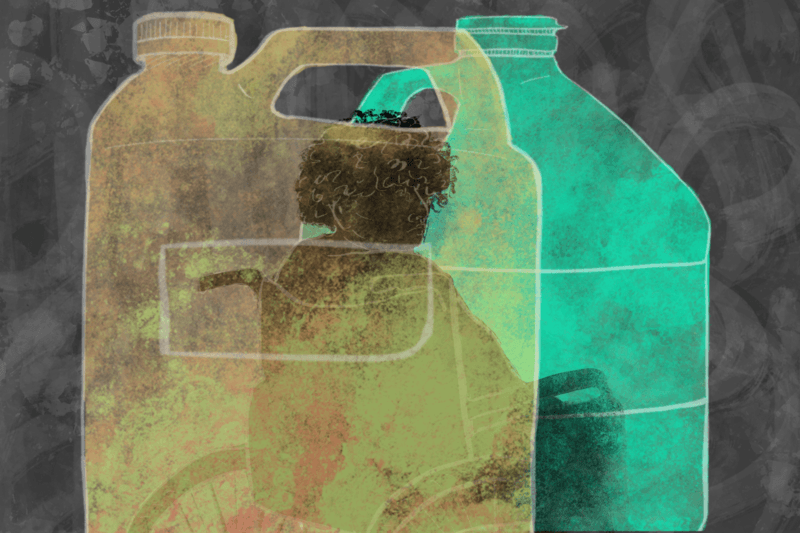

But instead of retrieving the GoLYTELY solution from a “squared-off” plastic jug in the refrigerator, it’s believed the caregiver grabbed a round, gallon-sized jug of Heinz All Natural Cleaning Vinegar.

Nearly five hours later, Wilson arrived at the doctor’s office for the procedure. While there, she began wheezing and having trouble breathing. As she struggled, Wilson reportedly told one of her caregivers, “This is a really s***** day.” An anesthesiologist listened to her lungs and ordered Wilson sent to the emergency room.

By the time she arrived at the hospital, Wilson was unresponsive and turning blue. She had a “do not resuscitate” order and was declared dead at 10:11 a.m.

The Spokane County Medical Examiner later determined Wilson died from ingesting household vinegar. The cleaning strength product, with six percent acidity, had inflamed and killed the tissue in Wilson’s esophagus, stomach and small bowel resulting in her death.

While the circumstances were unusual, the poisoning death of Marion Wilson highlighted an under-the-radar crisis that’s brewing in Washington’s community-based system of care for people with developmental disabilities. Caring for these vulnerable adults in their own homes has been delegated to private contractors who rely on a low-paid, high turnover (estimated at 50 percent) workforce that’s in constant short supply. As a result, the quality of care can suffer — sometimes with devastating consequences.

An ‘unqualified’ care provider

Wilson was a client of Aacres Washington, a Spokane-based in-home care provider that contracted with the state. Less than a year before, Aacres had taken over Wilson’s care after its sister company, SL Start, was decertified for a “history of serious … non-compliance with the law and regulations,” including failing to get appropriate and timely medical care for a client who subsequently died.

At the time, Disability Rights Washington, in a letter to the secretary of the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS), wrote that it had “grave concerns about an unqualified provider continuing to deliver services.”

But with 200 SL Start clients facing imminent displacement, DSHS’ Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA) said it had no choice but to contract with Aacres Washington to avoid a disruption of care.

Instead of the prescribed medicine to prep for a colonoscopy, Mary Wilson received and drank cleaning vinegar made by Heinz. Source: Heinz Co. /Amazon

Ten months later, Marion Wilson was dead.

“We are saddened by the death earlier this year of a client served by Aacres in Spokane,” DDA said in a statement last month. “We take events like this seriously and do whatever we can to help support our contracted providers to deliver appropriate services and supports.”

Approximately 4,200 developmentally disabled clients in Washington are cared for in state-paid community-based settings at an average reimbursement rate of $355 a day. By contrast, roughly 600 clients are living in the state’s four remaining institutions.

Despite the medieval nature of her death, what happened to Marion Wilson hardly made a ripple at the time. There were no news stories — those would come months later. There were no family members standing in front of the cameras demanding answers and threatening lawsuits. There wasn’t even an obituary in the local paper.

In fact, until recently, Wilson was known only as Client #1. The medical examiner finally released her name in November, nearly nine months after her death, following a request by public radio’s Northwest News Network.

Now, as the one year anniversary of Wilson’s death approaches, there have been new revelations in the case even as there are still more questions than answers about what happened.

“It seems really almost impossible to confuse those two liquids – colonoscopy preparation and vinegar,” said Betty Schwieterman, Washington’s Developmental Disabilities Ombuds. “Why were they confused, why were they in the same place, how did this happen?”

Answers may yet be forthcoming. In December, an investigator with the Medicaid Fraud Division of Washington’s Attorney General’s office obtained a search warrant for the Spokane headquarters of Embassy Management LLC, the private equity-owned parent company of Aacres Washington.

The affidavit in support of the search warrant included a dramatic revelation: the caregiver who allegedly gave Wilson the vinegar is under investigation for several crimes including manslaughter and assault. The Northwest News Network is not naming the caregiver because she has not been charged with a crime. Attempts to contact her were unsuccessful.

‘Public doesn’t know what happened here’

Despite this surprise development, for the past many months the circumstances of Wilson’s death have largely been shrouded in secrecy. That’s because, with few exceptions, the agencies responsible for investigating what happened won’t talk about the case or release relevant records. They cite state and federal laws designed to protect healthcare information, as well as the privacy of vulnerable adults and their caregivers. The result: when there’s a critical incident resulting in a serious injury or death, there’s little transparency or opportunity for public accountability.

“The purpose of confidentiality is to protect the victim, [but] here the victim is deceased,” said David P. Moody, a Seattle attorney who represents vulnerable adults and children in lawsuits against DSHS. “This tragedy occurred 10 months ago and the public doesn’t know happened here.”

In cases like Wilson’s, the cloak of secrecy is thick.

For instance, the Spokane County Medical Examiner refused numerous requests to explain how it reached the conclusion that Wilson’s death was an accident.

Adult Protective Services (APS), which is part of DSHS and is required to investigate all allegations of abuse involving vulnerable adults, asserts that its records are confidential and exempt from disclosure barring a court order.

APS also declined to release the results of a vulnerable adult fatality review that it was required to conduct following passage of a 2016 law. By contrast, Washington’s Child Protective Services posts all fatality and near-fatality reports online. (Last year, Washington lawmakers considered, but did not pass, a bill that would have allowed APS to release the outcomes of its investigations.)

A separate mortality review, completed by the Developmental Disabilities Administration, has not yet been released. In a statement last month, DDA said: “While we understand the public’s desire for details, we are required by law to protect certain client information.”

Even the independent Developmental Disabilities Ombuds is prohibited from confirming whether it’s investigating a case and its reports are not subject to public disclosure.

In fact, to date, the only publicly-available details about what happened to Wilson, besides the medical examiner’s findings, are contained in the recent search warrant affidavit and in an investigation conducted by Residential Care Services (RCS), a division of DSHS which licenses community-based providers like Aacres Washington.

The purpose of the RCS investigation, however, was not to answer how Wilson was given vinegar in lieu of colonoscopy prep. Nor did it seek to determine the culpability of individual staff members. Instead, the investigation focused on Aacres Washington and its practices as a certified provider of care.

A pattern of ‘serious deficiencies’

The findings of RCS’s investigation were outlined in a six-page letter sent last August to Embassy Management’s CEO. In the letter, RCS said Aacres Washington had failed to ensure Wilson received her colonoscopy prep medicine, delayed getting her medical attention and withheld relevant information – including the early suspicion that Wilson had been given cleaning vinegar.

The investigation also found that 18 employees of Aacres Washington had failed to immediately report Wilson’s death as required by the state’s mandatory reporting law.

“This inaction precluded the department from having immediate knowledge of alleged neglect of a vulnerable adult and delayed the department’s investigation,” the letter said.

Even before Wilson’s death, state regulators had documented “serious deficiencies” by Aacres Washington in Spokane that “jeopardized clients’ health, safety and welfare.”

Those deficiencies included failing to ensure a client received their medication and failing to report the mental abuse and isolation of three clients by a staff member.

“In this case you have a provider that had past citations for their medication management failures and failure to report abuse and neglect, so you had a pattern of these types of issues with this provider,” said Schwieterman, the Developmental Disabilities Ombuds.

In August, based on RCS’s findings, DDA abruptly cancelled all three of its contracts with Aacres Washington to provide in-home care in the Spokane area for 128 clients.

In October, RCS went a step further and formally decertified each of those contracts based on “a history of noncompliance.” Aacres is now appealing that decision.

The company declined an interview and did not answer a series of emailed questions about the RCS findings, but in a statement Embassy Management CEO Robert Efford said: “At Aacres Washington, we take the health and safety of our clients extremely seriously and were devastated by the death of this resident. We are committed to providing the highest level of care at our supported living homes and are working continually to ensure that each of our homes and care professionals is equipped to provide that care to our clients.”

The company continues to serve more than 200 developmentally disabled clients in Snohomish, Pierce, Thurston and Clark Counties.

In an interview last month, RCS Director Candace Goehring called Wilson’s death “tragic” and “unfortunate,” but said her division had done its job to protect the public.

“I would say there was accountability here,” said Goehring. “There was a contract and a certification that a company had that they no longer have.”

In the RCS investigation, the caregiver who allegedly gave Wilson the vinegar is described by a colleague as “very competent” and “dedicated.”

Nonetheless, in April, Aacres Washington fired her for violating the company’s medication administration policy. Three other staff members were issued warnings, according to the RCS investigation.

A paradox in life and death

Wilson’s death comes as Washington – like the nation — is experiencing a seismic shift in demographics. The population is aging and the number of vulnerable adults, including those with developmental disabilities, is growing. As a result, reports of adult abuse have reached “unprecedented levels,” according to DSHS. In 2018, APS received more than 60,000 reports of abuse and neglect, more than triple the number received six years earlier.

To this day, little is known about Marion Wilson. A sister in Oregon and the family’s attorney both declined to comment for this story.

A search of online databases failed to turn up any trace of Wilson, with one notable exception.

In 2012, Wilson was criminally charged with assaulting her then-caregiver who worked for Catholic Charities.

According to a Spokane Police incident report, obtained by the Northwest News Network, the caregiver was driving Wilson to an appointment when Wilson hit her on the arm.

The caregiver wasn’t injured, but reported the incident to her supervisor. Five days later, a Spokane police officer interviewed both the caregiver and Wilson and then cited Wilson for simple assault, a misdemeanor.

The case was ultimately dismissed. However, the episode highlights a paradox about Wilson’s life and death: when she socked a caregiver in the arm, the police came knocking. But years later when another caregiver allegedly gave her a fatal dose of vinegar, the police didn’t immediately investigate. (The case was referred to the Spokane Police Department, which in turn notified the Attorney General’s office.)

The fact Wilson died from ingesting cleaning vinegar wasn’t confirmed until the results of her autopsy were released.

But on the morning of Wilson’s death, Aacres staff suspected a profound mistake had been made. When the day shift caregivers arrived at her home, they discovered the unfinished colonoscopy prep solution in the refrigerator. They also found the empty container of vinegar in the recycling.

One caregiver brought the vinegar bottle to Wilson and asked if it smelled like what she had consumed. Wilson reportedly said “yes.”

When it was time to go to the doctor for the colonoscopy, the caregivers brought with them the remaining prep medicine. While at the doctor, Wilson “started wheezing, coughing and slurring words.” The caregivers eventually told a nurse of their concern that she had ingested vinegar. The gastroenterologist also reported Wilson “smelled like vinegar.”

As part of Aacres’ internal review of the death, which RCS obtained, the caregiver who allegedly gave Wilson the vinegar acknowledged she had “just grabbed the container” and had not checked the label before giving it to Wilson.

A second overnight aide reported seeing the staffer come back from the kitchen with Wilson’s special red cup and give her “a liquid to drink while in the bathroom.”

The state’s investigation would later identify several Aacres staff members who were aware of the possibility that Wilson had been given vinegar instead of the prep medicine, but didn’t say anything.

Months later, in July, state investigators would learn for the first time that Aacres management possessed written statements and photographs regarding the events surrounding Wilson’s death.

It was also at that time they learned a staff member had possession of the vinegar bottle in their office. By one account, it had been re-purposed to use as an ice melt spreader.

It’s unclear if the ongoing investigation by the Attorney General’s office into Wilson’s death will result in criminal charges. The investigator, in his affidavit seeking the search warrant, said the caregiver who allegedly gave Wilson the vinegar has so far not given a statement about what happened.

Related Stories:

New grant to help people with developmental disabilities find housing

Andrew Adams waters the garden outside the kitchen of his home. (Credit: Kristin Adams) Listen (Runtime 4:10) Read By Lauren Paterson and Rachel Sun For adults with developmental disabilities in

Washington Is Sending Youth In Crisis To Out-Of-State Boarding Schools; Taxpayers Pick Up The Tab

Some parents with kids in crisis in Washington are making a heart wrenching decision. They’re sending their children to out-of-state therapeutic boarding schools. And taxpayers are picking up the tab. While these are outlier cases, they highlight ongoing gaps in in-state services — gaps that were laid bare during the COVID pandemic.

He’s 13-Years-Old, Autistic And Stuck In The Hospital For The Holidays. He’s Not The Only One

It’s a growing problem in Washington: kids with developmental disabilities and complex behaviors who are stuck in the hospital with no reason for being there. Usually, they end up in the hospital after a crisis or an incident. But once the child is medically cleared to leave, their parents or their group home won’t come get them citing inadequate supports to manage the youth’s needs. While the state searches for alternative placements, the child waits.