The Woman Leading The Fiddle Revival In Country Music

LISTEN

BY JEWLY HIGHT

It’s common practice for chart-topping Nashville songwriters to see their accomplishments celebrated with lawn signs in front of industry offices, but Jenee Fleenor arrived at Sound Emporium Studios for her NPR interview to see a banner congratulating her on a different kind of milestone. This November, she became not only the first woman to win the Country Music Association’s Musician of the Year award, but the first fiddle player to be honored in more than two decades.

Her journey started in the late 1980s in small-town Arkansas. Back then, Fleenor was a 3-year-old classical violin student studying the rigorous Suzuki method. Her father picked up the instrument, too, and learned right alongside her, while her mother accompanied them on piano. But when their daughter was 5, Bob Wills‘ western swing classic “Faded Love” transformed her into a fiddler.

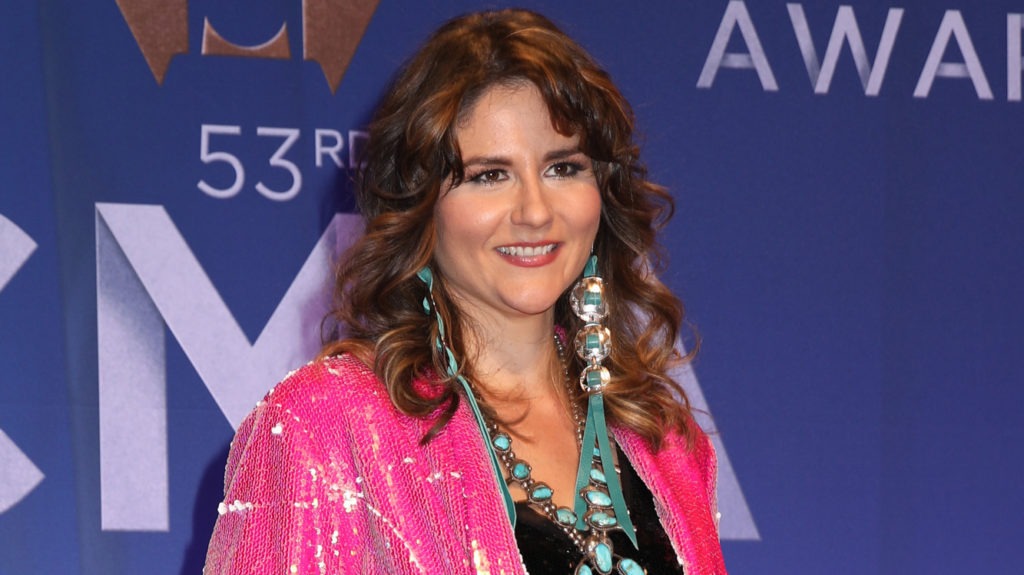

Jenee Fleenor at the 53rd annual CMA Awards on Nov. 13, 2019 in Nashville, Tenn., where she was honored as the first woman to win Musician of the Year.

CREDIT: Leah Puttkammer/Getty Images

“I’d heard it so much in the background and I just picked up my fiddle one day and started playing it by ear,” she says. “And honestly, that is the moment that I was like, ‘Wow, I can kind of play what I want to on this thing.’ ”

What she wanted was to explore the country side of her instrument, and her parents were willing to drive her anywhere that could happen.”There was a[n] Arkansas fiddle association down the road from me,” she recalls, “and I’m, like, maybe 7, 8-years-old and it’s all men over 60, probably. So, I mean, really, throughout my whole life, I’ve been playing with a bunch of hairy-legged men.”

By age 10, she was in the staff band at a regional Arkansas opry house. Then, it was on to lessons, camps and fiddle contests and a host of other performing experiences — with a bluegrass outfit, at steel guitar conventions, even during the halftime show of her high school marching band, for which she served as drum major. “I played through this megaphone thing we rigged up,” she says. “Any chance there was for me to play fiddle, of course, I’d always step up to the plate.”

When Fleenor stepped into a local studio for a small-time recording session, she found something she enjoyed even more than performing live. “I just remember putting those headphones on and hearing my fiddle through that microphone,” she says. “And I’m sure it had some reverb in it. And I was like, ‘Oh, my gosh, this is the best my fiddle maybe ever sounded.’ It just was a spark in me.”

She began researching the musicians who backed the stars on country radio, and even tracked down a few of their email addresses. “Those were the guys that I wanted to play music with,” she explains. “I wanted to play music with people that were better than me. I always had that desire.”

She especially zeroed in on fiddler Mark O’Connor, who seemed to play on just about everything in the ’90s and had six consecutive CMA Musician of the Year trophies to show for it. “I’d buy outfits and little hats that probably tried to look like Mark O’Connor,” she laughs. “That was my fan girl moment. Other people were trying to be, I don’t know, Shania Twain. Here I am trying to be Mark O’Connor.”

What helped Fleenor’s prospects more than costumes was moving where the action was in 2001. A couple of weeks after she arrived in Nashville, Tenn. for college, she ran into a friend at a bluegrass show, who then asked his boss, Larry Cordle, if Fleenor could sit in with the band that night. Cordle — a songwriter known for “Murder on Music Row,” a tune that laments the loss of traditional country elements like fiddle — loved what he heard.

“I actually wanted to ask her that night if she wanted to work,” he says. “But I made myself wait till Monday.”

And when Cordle did call to offer the gig, he was mindful of the fact that his potential fiddle player was still in her teens. “I said ‘Well, you tell your mama that I’ll take real good care of you. I’m going to help you,’ and all, this whole big sales pitch,” he says, but recalls Fleenor insisting, ” ‘I don’t have to ask my mom!’ ”

With Cordle, Fleenor became a featured vocalist and got into songwriting. She left college to take bigger touring gigs, first with Terri Clark, then Martina McBride, but the work required learning licks laid down in the studio by first-call fiddlers. “The bands that tour with the artists — you have to learn the parts just like the record, for the most part,” Fleenor explains. “So I was learning Stuart Duncan’s licks on those Terri Clark records … I think [what] people don’t realize about Nashville [is] that what you’re hearing on the record is usually not the road band. They’re two separate things. Especially back in the ’90s, if you had a road gig, sometimes it was the kiss of death that that you wouldn’t be able to do the session work. When I first moved to town, it was it was a lot like that.”

By the early 2010s, there was less demand for fiddle in general, as contemporary country leaned harder on its hip-hop, pop and rock influences. Fleenor adapted by picking up acoustic guitar and mandolin. “I didn’t want to,” she says, “but I realized to keep a gig and to get future gigs, that’s what I need to do.”

Her studio fiddling was sporadic until she got a call from a young artist named Jon Pardi, who was trying to land a major label deal with a hard country sound. “Nashville’s like ‘follow the leader’ sometimes, you know?” Pardi says. “And so you’ve got all these artists that aren’t really incorporating this fiddle and steel. But then I came from California and was high energy. I had a fiddle player. I studied country music. I knew what to do with these instruments. And you knew what to listen for in players. Jenee’s automatic, man.”

Fleenor recalls that Pardi and his longtime co-producer, Bart Butler, urged her to take a gutsy attack on recordings. “I mean, it really is a dream as a fiddle player,” she says. “They’re like, ‘We want you on the intro. We want you on the solo and doubling guitar licks.’ [Combined] steel guitar and fiddle lines, they’re called gang licks. And to hear that on a record — again, oh my god.”

Pardi’s single “Heartache Medication” was the first radio hit in a good, long while to kick off with fiddle. By the time he released the album that shares its title — the third on which he’d featured Fleenor — people had come to recognize her signature playing, from vigorous, bluesy double stops to blistering runs that emulate metal-style guitar shredding.

“I can definitely be very traditional. But then, you know, if there’s a call to be outside the box, I try to be that too,” she says. “I owe a lot to Jon for fiddle and steel guitar turned way up in the mix. And I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, maybe this thing will come back around someday.’ Not really thinking that maybe I would be the one that might help turn the thing a little bit.”

Eighteen years into her Nashville tenure, Fleenor splits her time between working in the studio and high-profile slots backing Blake Shelton and Steven Tyler. Her industry peers decided this was the year to give her one of the highest honors a country player can get.

“There’s not a whole lot of female [musicians] in this business, you know? And I think a lot of people were excited about [the win],” she says. “I honestly never thought about it too much. Being a session musician was just what I want to do, and I never thought I couldn’t do that because I was a [woman], you know? It’s just something I wanted, and I went after it and got it. There [have been] a few times when I’ll step in the studio, and you just get this look or somebody just thinks maybe you don’t know what you’re doing. And I always just say the proof’s in the playing.”

Fleenor’s way of marking the occasion was to make a little music of her own. Shortly after claiming her award, she released a single under her own name called “Fiddle & Steel.” She’d co-written the song expecting it to be pitched to a male singer, but decided she should be the one to deliver it. “I put details in there that cater to my life,” she explains, just as she’s always sought out openings she could make her own.

9(MDAyOTk4OTc0MDEyNzcxNDIzMTZjM2E3Zg004))