‘Dangerous Melodies’ Examines Classical Music And American Foreign Relations

LISTEN

BY SCOTT SIMON & ANDREW CRAIG

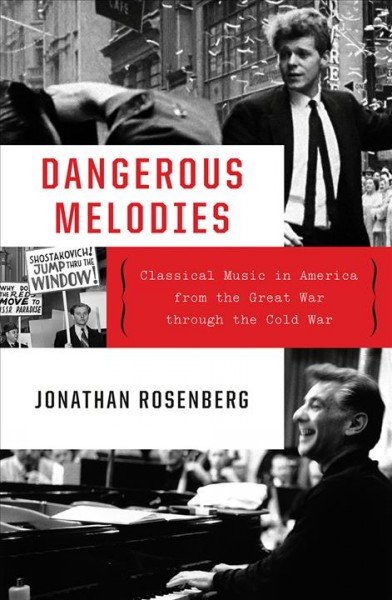

At the height of the Cold War in 1958, Van Cliburn, a curly-headed kid from Texas, won the International Tchaikovsky Competition. He was hugged by Nikita Khrushchev and heralded like Elvis Presley when he returned.

Classical music figures were once stars in America. They were pursued, recognized and gossiped about — people who had popular and cultural impact. Jonathan Rosenberg, a professor of history at Hunter College, has a new book that examines this phenomenon. It’s called Dangerous Melodies: Classical Music in America from The Great War through the Cold War.

Van Cliburn moves through difficult passage in the final round of Tchaikovsky International Piano & Violin competition on April 11, 1958 in Moscow. CREDIT: AP

NPR’s Scott Simon talks to Rosenberg about some of the genre’s influential figures, including Van Cliburn, Richard Strauss and Aaron Copland. Listen in the audio player above and read on for highlights of their conversation.

Interview Highlights:

On Van Cliburn’s popularity during the Cold War:

Van Cliburn went off to Moscow and won the [International Tchaikovsky] Competition. This was seen as a victory for the American system — the idea … that he could go over there and win this competition and receive praise from Russians suggested to people that perhaps the United States was not comprised of a bunch of materialists and barbarians. In many circles, that was how we were seen.

On the public denouncement of German classical music in the U.S. during World War I:

There was, throughout the country, tremendous anti-German sentiment. Classical music was swept up in this anti-German sentiment — quite distressingly, I might add. The Metropolitan Opera company, for example, banned all German opera starting in the 1917-18 season. The music of living German composers was banned in most places in the United States, including the music of Richard Strauss, and musicians in the orchestra also lost their jobs. This happened across the country. Obviously, it manifested itself in different ways, but the world of classical music in the United States — East, Midwest, West — was affected adversely by this.

“Dangerous Melodies:

Classical Music in America from the Great War Through the Cold War” by Jonathan Rosenberg

On the significance of Arturo Toscanini’s concert in April 1933:

Toscanini and a number of other musicians in the United States sent a cable to Adolf Hitler, basically saying that Hitler ought to the stop the depredations against musicians in Nazi Germany. There were some who were not Jewish musicians, but in the eyes of the Nazi regime, they were transgressives. Toscanini was asked to become part of this effort and he said “Absolutely, I will certainly do that.” It was seen as quite an important event in the United States at the time.

On Aaron Copland’s experience during the McCarthy era:

I think an Illinois congressman came to understand that Aaron Copland’s political sentiments were, let us say, questionable. This congressman made quite a fuss about it and in fact, [his piece “Lincoln Portrait”] was taken off the “play list” for [Dwight Eisenhower’s] inaugural. Copland was exorcised about it. Others were as well, but there was worse to come for Copland. He was interrogated, if you will, by McCarthy and Roy Cohn. The larger point is: he was a person who, as you said earlier, represented in his music America’s highest patriotic aspirations. And nevertheless, he was drawn into the toxic quality of the McCarthy era, being called before that committee, and after that, in fact, he was banned from performing and he suffered.

On the role of classical music today:

I’d like to think that in a culture that is often distracted, that seems at times to be spinning madly out of control, that it allows people the opportunity to appreciate music that was produced in another era — which can be, I find, uplifting. Quite frankly, to me, it would be desirable if people were open to listening to it, because I think it can be really rather enriching to sit down and listen to a symphony or a string quartet. I think that would be nice, if classical music could yet again become something that people were willing to devote at least a little time to.