American Samoans’ Citizenship Status Still In Limbo After Judge Issues Stay

BY VANESSA ROMO

John Fitisemanu woke up early Friday morning, got dressed and finally completed one of the tasks on a more than 20-year-old to-do list: He registered to vote.

For less than a day, Fitisemanu, who was born in American Samoa, was legally considered a full-fledged American citizen with voting rights and the ability to run for office or hold certain government jobs. But a judge in a Utah federal court has once again thrown his much longed-for status into question.

After ruling on Thursday that anyone born in American Samoa should be recognized as a U.S. citizen, the same judge — U.S. District Judge Clark Waddoups — on Friday decided to put the order on hold until the issue is resolved on appeal.

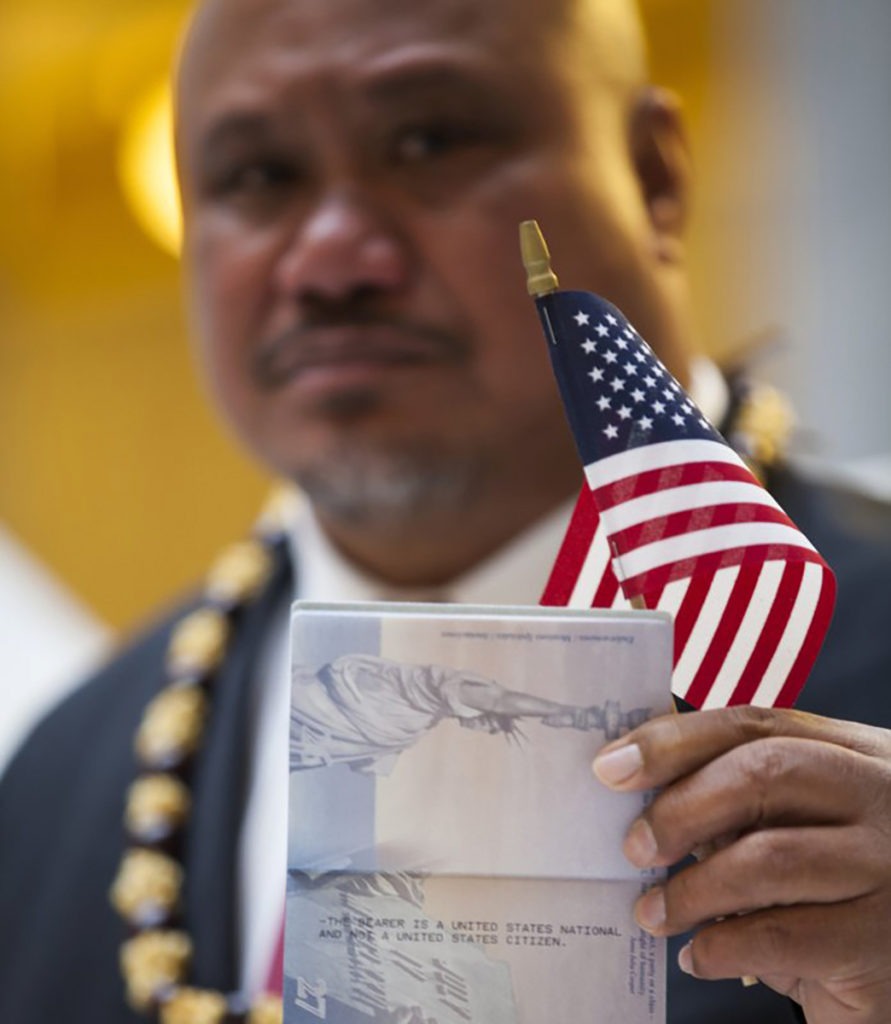

John Fitisemanu, an American Samoan, filed the lawsuit against the U.S. government after he was denied the opportunity to apply for federal government jobs listing citizenship as a requirement. CREDIT: Katrina Keil Youd/AP

Since becoming a U.S. territory in 1900, the cluster of Pacific islands southwest of Hawaii has remained the only territory not granted birthright citizenship. Instead, people there are identified as U.S. nationals. That means they are not allowed to participate in federal, state or even local elections in the U.S. They cannot run for any elected office and they’re also denied from applying for government jobs that require citizenship. They’re also issued passports that say, “This bearer is a United States national and not a United States citizen.”

Fitisemanu and two other American Samoans who also live in Utah sued the federal government to change all that. And Waddoups agreed.

“Any State Department policy that provides that the citizenship provisions of the Constitution do not apply to persons born in American Samoa violates the 14th Amendment,” Waddoups wrote in a 69-page judgment on Thursday.

The decision contradicts a 2015 ruling in federal court in Washington, D.C., that determined only Congress can resolve questions of citizenship within the nation’s territories. And government attorneys plan to appeal Waddoups’ decision.

Neil Weare, a lawyer for Fitisemanu, Pale Tuli and Rosavita Tuli, said his clients are eager to have the issue resolved once and for all and “be able to enjoy all the same rights as their fellow Americans.”

In the case of Fitisemanu, who has lived in Utah for more than two decades, Weare said he’s been a hardworking, taxpaying American. “Yet, based on this discriminatory federal law, he’s been denied recognition of citizenship by the federal government and as a result he’s not able to vote.”

“All he wants is to have his voice be heard, just like any other American would,” Weare added.

In his younger years, Fitisemanu dreamed of landing a government job and all of the security and wages that come with it. “And when he looked in terms of the jobs qualifications, it said, you must be a U.S. citizen. So he was not able to pursue those very attractive, well-paying jobs,” Weare explained.

It was that experience that prompted Fitisemanu, now 56, to file the lawsuit.

Government attorneys dispute the argument that citizenship decisions can be made in federal courts. Their position is that only Congress possesses that power.

“Such a novel holding would be contrary to the decisions of every court of appeals to have considered the question, inconsistent with over a century of historical practice by all three branches of the United States government, and conflict with the strong objection of the local government of American Samoa,” government attorneys wrote.

The government of American Samoa sided with U.S. attorneys, arguing that “imposition of citizenship by judicial fiat would fail to recognize American Samoa’s sovereignty and the importance of the fa’a Samoa [the Samoan way of life].” Additionally, they maintain that an “imposition of citizenship over American Samoan’s objections violates fundamental principles of self-determination.”