‘Do Something Big’: Photographer Helps Tell Columbia River History In ‘Healing The Big River’ Book

READ ON

UPDATE: Dec. 16, 2019: This article has been updated to clarify “First Nations” as referring to groups in British Columbia and Canada, and for “tribes” to refer generally to those in the United States, since that is the more accepted terminology. Additionally, because of a transcription error in the section “On The Columbia River Treaty,” the term “First Nations” has been changed to accurately show that Peter Pochocki Marbach said “firsthand” in referring to the U.S. State Department and tribes in the United States.

Standing on top of Oregon’s Mount Hood, photographer Peter Pochocki Marbach looked down to the Columbia River, snaking its way through the gorge to the north.

He’d undergone open heart surgery eight months earlier. Hiking along the river’s edge helped him recover.

He watched as the water stretched on forever.

“I made a promise that at some point I would do something to honor the Columbia and thank the river for its role in helping me heal,” Marbach recalls. “So I said, ‘Someday I’m going to do something.’ But that someday took a long time.”

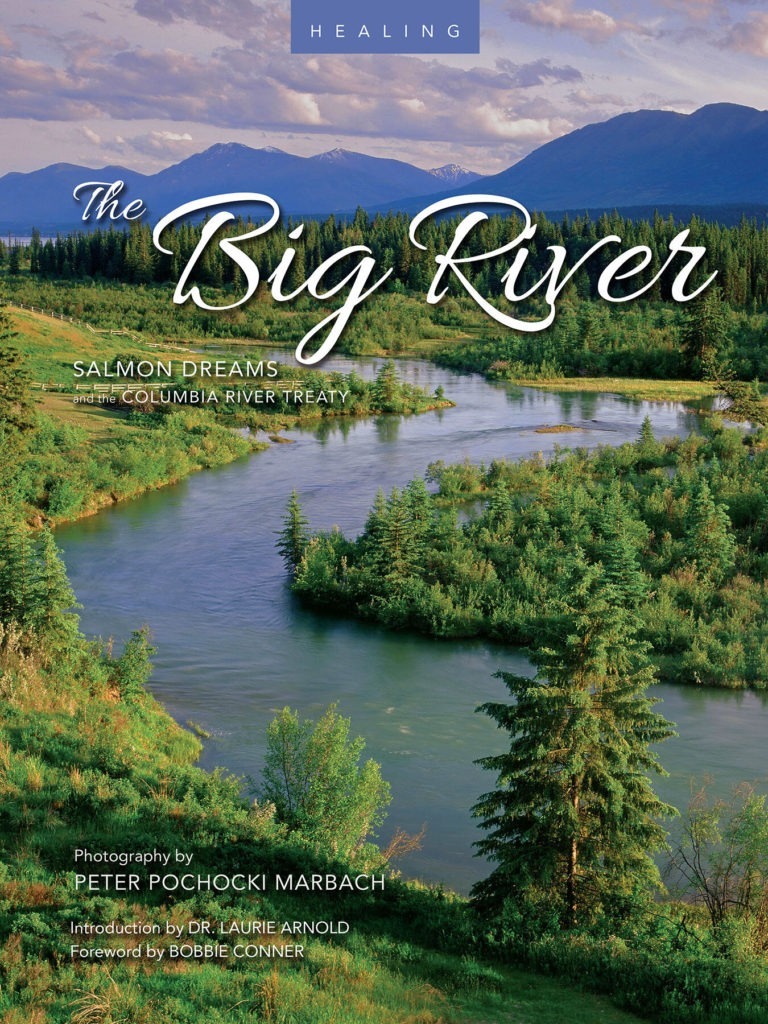

It took him more than 10 years to “do something big” and finish his book Healing The Big River: Salmon Dreams and the Columbia River Treaty. In that time, he’s traversed the Columbia, from its headwaters in British Columbia …

‘Healing the Big River’ by Peter Pochocki Marbach

“I just about passed out with joy because it’s so unbelievably beautiful. It’s like this is the scene out of out of a dream, with this river running wild and free,” he says.

… to its mouth at the Pacific Ocean.

Marbach says he wanted to use his photography to tell the story of the river, to move from purely landscape images to a more social justice-driven book. To do that, he needed help.

“I want this to be told primarily from tribal and First Nations perspectives. One by one, I started asking people, and it just worked out,” Marbach says. “It represents people from the headwaters all the way down to the ocean.”

In the book, Marbach called on 12 contributing authors to write about their hopes for the Columbia, especially in light of the ongoing negotiations of the Columbia River Treaty.

The treaty was originally signed in 1961. It coordinates hydropower and flood control between the U.S. and Canada. For both the original negotiations and these most recent meetings, tribes in the U.S. have been left out of official meetings. They’ve met with officials separately to push for the treaty to include protections for salmon.

Essays in the book detail the importance of salmon and the river and how that all ties into the treaty.

One essay by DR Michel, executive director of the Upper Columbia United Tribes, tells of recent ceremonial releases of salmon into the upper portion of the river, where salmon hadn’t swam for almost 80 years.

Michel helped release salmon at Kettle Falls in August 2019.

“For one day, my fellow tribal citizens and I were able to truly give back and carry forth our responsibilities to those salmon spirits. Through work of generations of people to bring salmon back to their historic habitats, we were able to realize a small part of the overall goal of a healthy and sustainable salmon run back to their home where they belong,” Michel writes.

In an interview, Michel said this new treaty needs to include protections for salmon, especially in the face of climate change, which is expected to continue to warm waters and impact river flows.

Alfred Joseph, Chief of Akisq’nuk First Nation in British Columbia, a contributing author to “Healing The Big River.” Joseph tells of when his grandfather waited on salmon to arrive upstream. None did. Later they learned that Grand Coulee Dam had been built. “We are still waiting,” he said. CREDIT: Peter Pochocki Marbach

“Those processes have provided us opportunities to step back and take a different look at the system and how we can all better use those waters and those resources,” Michel said.

He said it doesn’t have to be an “either – or” situation.

“We can have fish passage and good, clean functioning ecosystems. We can provide power, and we can protect those folks who continue to build in the floodplain,” Michel says.

To Michel, things have changed since the treaty was originally negotiated, and the treaty should change with them.

Peter Marbach straddles the headwaters of the Columbia River near Canal Flats. CREDIT: Peter Pochocki Marbach

“I think it’s important to listen to folks and try to understand where they’re issues are and where coming from,” Michel says. “To work with them to see if we can come to some understandings and mutual benefits. We’re all going to have to give a little bit in this process.”

But he believes negotiations need to look beyond wallets and financial considerations to the resources we’re using.

“What we do today has huge impacts on our future generations’ ability to continue to utilize this river and other resources as we have,” Michel says.

For his part, photographer Peter Pochocki Marbach hopes his book will help further those conversations.

Like at an upcoming town hall. U.S. Rep. Dan Newhouse, whose district includes much of central Washington along the river, will host discussions from 5:30 to 7 p.m., Monday, Dec. 16 at the U.S. Federal Building in Richland. Newhouse had previously asked for a venue for people in the Mid-Columbia to offer input on modernizing the treaty.

Peter Pochocki Marbach Interview Highlights

Answers have been edited for length and clarity

On Starting ‘Healing The Big River’

When I made my first pilgrimage some 13 years ago up to the (Columbia River) headwaters, I just about passed out with joy because it’s so unbelievably beautiful. It’s like this is the scene out of out of a dream, with this river running wild and free for some 200-kilometer stretch between two mountain ranges, maybe 20 yards across running forever and this undulating series of curves.

So you just start from that angle of, ‘Oh, my God. This is so beautiful. I have to share this with people.’ But then I started meeting First Nations people along the way and started hearing their stories. And I was like, ‘Wow.’ I just had no idea about the impact of the Grand Coulee Dam. Some 80 years later, people up there still waiting for the fish to come back some day.

The Purcell Mountains reflect in calm water near Spillimacheen, British Columbia. CREDIT: Peter Pochocki Marbach

So it just really sort of tugged at my combination of my heart strings and my desire to do more with my photography on a more sort of social justice, environmental importance phase of my life, as opposed to just being in a pure landscape photographer.

On The Columbia River Treaty

The big thing that jumped out to me was that I thought it was unbelievable that during the first (Columbia River) treaty that the tribes were not invited to participate. There was no involvement for them, and no consideration for the impacts upstream or to make any mitigation efforts to to fix things. And I just thought, ‘Well, that was just terrible. That was just completely wrong.’

Fast forward to the (modernization of the) treaty, which is underway as we speak. In the United States side, our State Department has not invited complete representation for (tribes) firsthand sitting at the negotiating table. I have been made aware that the State Department has had some sidebar meetings with individual tribes. But in terms of being an official negotiator at the negotiating table, I just think that’s so morally reprehensible to not have them officially there.

At least the Canadian side, the B.C. government has granted observer status to three First Nations, which is great. I would hope that the United States would at least follow suit at that level.

On Including Salmon Protection In The Treaty

The treaty is not just good for tribes – it’s good for everybody. And if you reintroduce the salmon and end up into the Lake Roosevelt and up into Canada, I mean, everyone’s gonna benefit.

The salmon are just existing out of sight, out of mind. And the tribes have been waiting for a really long time to get this fixed. There’s a lot of hope. There’s a lot of optimism that things are going to eventually work out. But who knows how long this will take?

It’s like a lot of things in life. It just takes political will. And getting over bureaucratic inertia, it’s going to take time. But you’ve got to start somewhere.

On His Photographs In The Book

The imagery that I selected for the book – out of the bazillion photos that I got to edit down to whatever are in there, a hundred – are largely there to just give us sort of a sort of a greatest hits highlights of the geography and topography of the river. They were really selected to go more with the stories and essays.

Related Stories:

Canadian leaders hope trade negotiations won’t derail Columbia River Treaty

A view of the Columbia River in British Columbia. The Columbia River Treaty is on “pause” while the Trump administration considers its policy options. However, recent comments by President Donald

Feds update Columbia River Treaty flood risk management

Grand Coulee Dam in eastern Washington. Changes to the Columbia River Treaty could mean more flood risk management is controlled at the dam. (Credit: Shutterbug Fotos / Flickr Creative Commons)

Preliminary agreement reached for a modernized Columbia River Treaty

The Columbia River west of the Gorge as it heads toward Portland and out to the Pacific Ocean. (Credit: Amelia Templeton / OPB) WATCH Listen (Runtime 1:01) Read After more