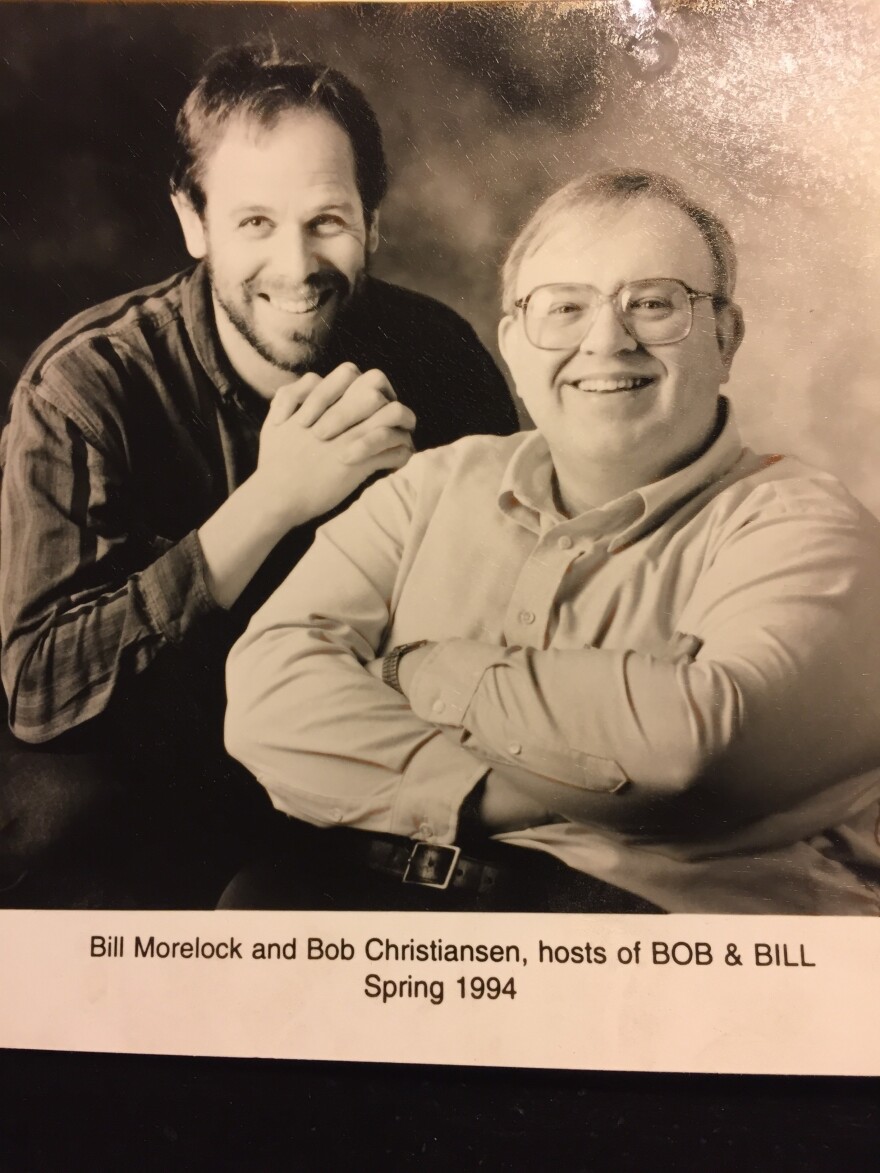

Beloved classical music host, Bob Christiansen, passed away. Many listeners may remember him as part of the duo, Bob and Bill. The syndicated show was created while at Northwest Public Radio in 1987. In 1992, the hosts moved to Minnesota Public Radio.

The following is a remembrance by Bill Morelock.

My friend and colleague Bob Christiansen died on November 11 in a care facility in Woodbury, Minnesota. He'd been diagnosed with metastatic melanoma late this summer. He was 72.

My experience with Bob is inextricably linked with Northwest Public Radio. He moved to Pullman early in 1987 from Phoenix, where his classical station had changed formats and he got the boot. I was there already, having been allowed gradually to get less bad at my job over the course of five years. In casual conversations I noticed something in his entertaining talk that did not, at that point, make it on the air. Rhetorical play, wit, almost a kind of poetry. Certainly, a raw poetic sense. I decided I must exploit, and of course learn from, this man.

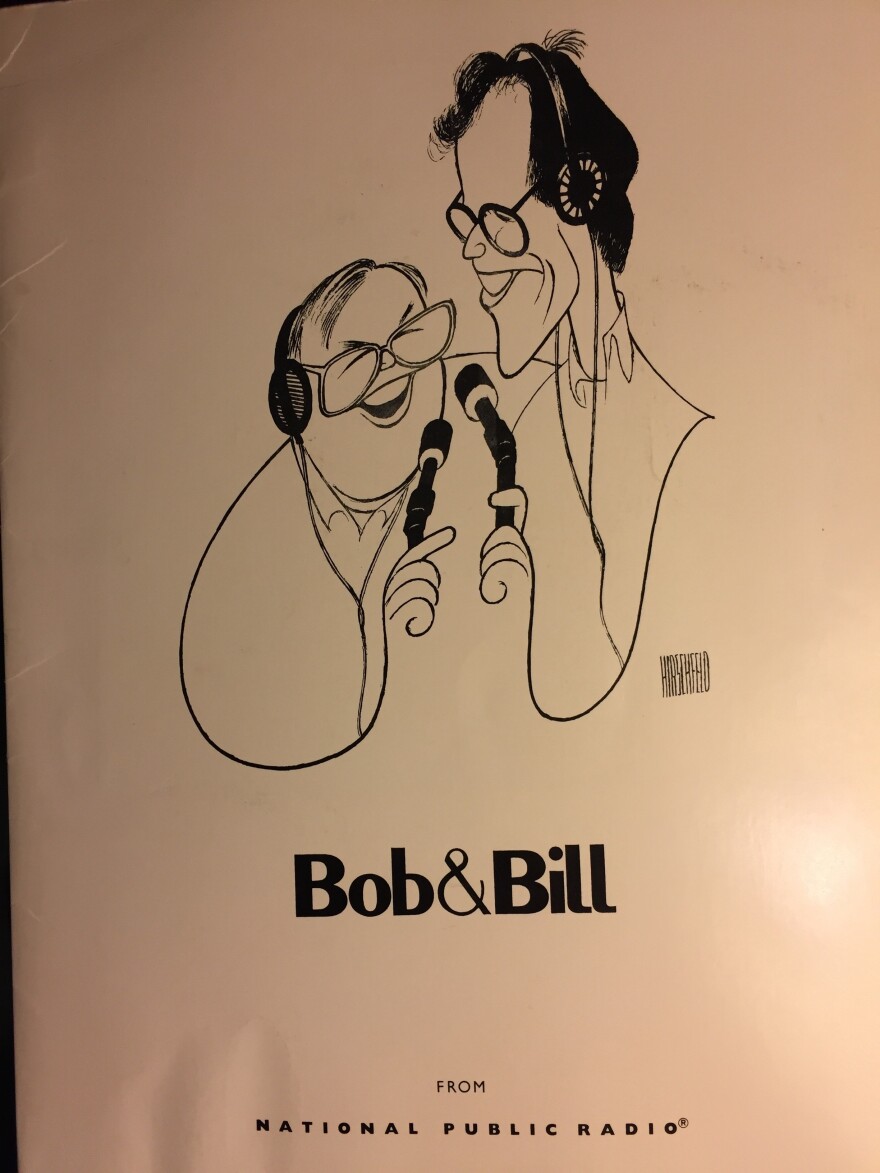

We began a collaboration a classical music radio show in 1988. It was unique, it was a conversation, a two man tag team affair through which we attempted to treat the appreciation of this music of many centuries not with sacerdotal ritual and hushed tones, but with anecdotal play drawn from a rich history, and whimsical connections to the current culture, and the way we live today. Lacking, or perhaps spurning a more dignified name, we called it Bob & Bill.

It wasn't immediately hailed as a welcome innovation. We received no happy mail for at least three months. Memorable in that gallery of pain was a letter from a woman in Palouse likening us to "two pre-adolescents out behind the barn smoking cigarettes and telling dirty jokes." Well. I might have responded that Bob had quit smoking in 1973 and that we never worked blue. But one doesn't always muster the presence of mind for the perfect bon mot when you're having hot tar poured on your head by the righteous defenders of musical piety, apple pie, and civilization itself against a couple of hapless barbarians at the gate. We just wanted to make good radio with a kind of music we felt had not much received such a treatment. Classical music broadcasting called to mind a deep baritone voice that had emerged from a coffin long enough to intone "Johann Sebastian Bach" with an impeccable diction and accent, introduce "Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart" in identical fashion, and then climb back into the coffin until the Prague Symphony was over.

There was a lack of oxygen. It was hard to breathe, much less improvise, or, Brahms forbid, laugh! We gleefully committed all these breaches of decorum.

Radio was the key, our medium, and to it we owed our allegiance. Of course, we enjoyed the music, loved the music, devoured biographies and histories to unearth the vivid fact on p. 503. That's where the good stuff is. But it was all in the service of the craft of radio.

Things got better, we got better. Grudging acknowledgements that we weren't terrible, that probably we weren't going to burn down the place, that maybe newer music, American music, stories of foibles and enmities, of Bach's bad bosses, of Bartok on his death bed heroically creating against time, of Brahms' transcending a cruel childhood--maybe these things suggested the marble busts getting some color on their cheeks; that these musical monuments were the products of human imaginations. And that as human beings, we should resolve to be proud.

In the end, we came to believe that whatever else this music is or means, it is, or can be, the richest radio format in the world. Because with its natural bridges to history, art, literature, language, popular music of all eras--even science, philosophy and theology--classical music is, for a broadcaster and listener willing to take a panoramic view, a radio format about absolutely everything.

That was our partnership, that was our education, and we treasured the years.

Bob gets the last word, the briefest of elegies at the end of this longish eulogy.

Given his talent for synthesis, for distilling down the details of an opera plot or a composer's character into a strong concentrate, I offer a single-verse assertion, in limerick form (for an impish force was strong with this one), that classical music and pure play can combine to make something memorable.

His description of young Walther von Stolzing, the hero of Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, serves equally well as an example of Bob's craft and a description of his own long song.

Farewell, my friend; it's been a privilege.

There once was a knight from Franconia,

Whose singing was pure and unphonia.

The contest was won by singing for fun,

Without all the rules and balonia.