Booked And Buried: Jail Suicide Epidemic Doesn’t Extend To Northwest Prisons

Read On

NOTE: This is another story in an on-going series called “Booked and Buried,” reporting on deaths in Northwest jails. If you have a tip or a story idea, email us.

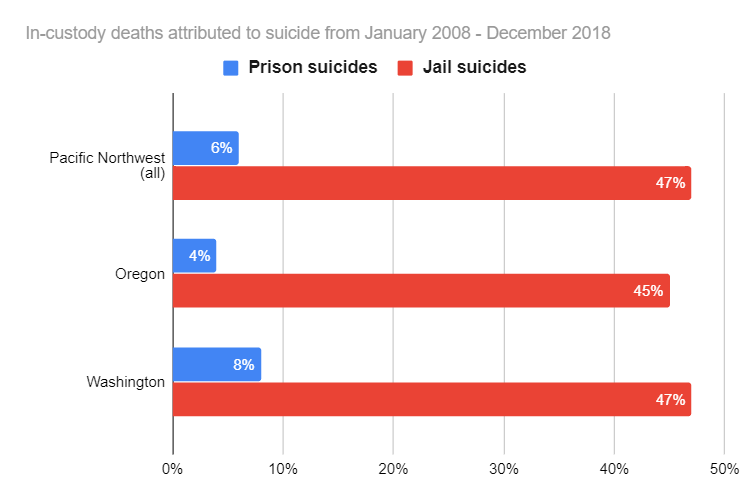

In county jails across the Pacific Northwest, suicide is the single leading cause of inmate deaths. But an analysis by OPB shows the region’s prisons aren’t plagued by the same crisis.

Between 2008 and 2018, suicide accounted for 47% of jail deaths with a known cause in Oregon and Washington, according to an investigation by OPB, KUOW and the Northwest News Network.

A new analysis shows suicides in Northwest prisons during the same time period are a fraction — just 6% — of deaths in those facilities.

The discrepancy between suicides in jails and prisons not only points to the scale of the suicide epidemic in the region’s county jails, but also the challenges local jail officials face in trying to keep people safe as they wrestle with issues like substance use disorders and mental illness. Experts say prisons also have a lower suicide rate, in part, because there’s less uncertainty about an inmate’s future compared to when a person is first arrested and jailed.

Prisons vs. jails

Unlike prisons, which primarily hold people who have been convicted of a crime, anyone can end up in jail as they await the disposition of their case. Every year, approximately 440,000 people are booked into jails in Oregon and Washington. Closer to 13,000 are sent to Northwest prisons.

“It’s a revolving door of thousands of inmates going through the local jail system. That contributes to the sheer numbers,” said Lindsay Hayes, project director for the National Center on Institutions and Alternatives. “If you have more numbers of inmates, you’re going to have the opportunity for more suicides.”

National data comparing suicide rates among people who are incarcerated are limited. The federal Bureau of Justice Statistics last compared deaths in prisons and jails several years ago, but only published national and statewide suicide data, not information about individual county jails.

In 2013, the report found 327 people died by suicide in jails nationwide, which represents 33.8% of all jails deaths for that year. The same year, 192 inmates died by suicide at prisons across the country, accounting for just 5.5% of prison deaths. Data show overall more people die in prisons than in jails, but the leading cause of death in prisons is illness.

OPB’s analysis offers the first regionwide look that compares suicides in prison and local jails.

CREDIT: OPB

In Washington state prisons, about 8% of inmates who died, or 35 people, died by suicide between 2008 and 2018. In Washington’s jails, 47% of inmates who died, or at least 85 people, died by suicide.

In Oregon’s prisons, nearly 4% of inmates who died, or 15 people, died by suicide during the same 11-year time period. In Oregon’s jails, 45% of inmates who died, or at least 37 people, died by suicide.

Instability

One of the reasons suicides are more prevalent in the jails compared to prisons is that people in jails are often closer to the crisis that got them arrested in the first place.

“It could be related to their family, it could be the crime that they may be accused of — all those things are very fresh in their mind and there’s a lot of uncertainty. So I think just from a psychological perspective, that could be a taxing thing,” said David Cloud, senior program associate at the Vera Institute of Justice, a nonprofit that focuses on the criminal justice system. “There’s a lot of just things up in the air and people feel, I would imagine, pretty powerless in that situation.”

“Most people come to jail on the worst day of their life. In prison you’ve been in jail for awhile and so to some of them, it’s another day,” said Capt. Lee Eby, commander of the Clackamas County Jail.

In Eby’s jail, like many others in the Northwest, staff are working with people in challenging situations while dealing with a lack of funding and overcrowding.

The Columbia County Jail is pictured Saturday, March 30, 2019, in St. Helens, Ore. In 2016, two Columbia County inmates attempted suicide on the same day. Deputies revived one, but 44-year-old Jason Shaw later died at a Portland hospital. He had hanged himself using a bed sheet. CREDIT: Bradley Parks/OPB.

“Jails become the de facto emergency rooms, mental hospitals, treatment facilities, they are kind of the catchall of everything that society doesn’t have a resource for,” Eby said. “That’s not the intent and purpose of jails.”

Cloud said on top of trauma, many people who enter jails are experiencing withdrawal from drugs or alcohol, which isn’t typically a factor for people entering prisons. He said most jails do a poor job of addressing people’s medical needs around withdrawal.

On top of grappling with substance abuse withdrawal, jail inmates are almost entirely pretrial. Anxiety about how an open criminal court case will proceed can further elevate a person’s risk of suicide.

By comparison, most people who enter prison have resolved their initial court cases and have a better understanding of their future.

“People may regain a little stability in that process,” Cloud said.

While Cloud said “prisons are no place I would wish on my worst enemy,” he added that they are comparatively more stable than jails, where inmates have little to do other than “contemplate the chaos in their lives.”

Changing population

Suicides in jails have been a known issue since at least the 1980s. And experts say they are preventable.

“I used to hear the complaint of, ‘We can’t prevent suicides because they’re not preventable,’” Hayes said. “Now, the complaint of the sheriff is, ‘I run the largest mental health system in the county.’”

Hayes said that complaint has merit, as community resources for mental health have declined. Across the country, he said, many state-run mental hospitals have closed. Those that remain open are difficult to get into.

But Hayes added that the lack of mental health services shouldn’t be an excuse to let inmates languish.

“You can’t continue to complain about it, you have to do something about it,” he said. “You have to staff your jail to accommodate this changing population that’s coming into your jail. That’s where the issue is now.”

n Washington, inmates with mental illness languishing in local jails prompted a federal lawsuit, which resulted in the state needing to speed up admissions at the state’s two remaining psychiatric hospitals. The current state budget includes $74 million to fund diversion and outpatient treatment for inmates who are too mentally ill to stand trial.

This year, a similar lawsuit occurred in Oregon for inmates who were awaiting admission to the Oregon State Hospital. To get out from under the lawsuit, the Legislature passed Senate Bill 24, which made it more difficult to send people charged with misdemeanors to the state hospital for treatment while they awaited trial.

Hayes said sheriffs need to advocate for more resources to properly address inmates’ mental and behavioral health issues.

He said they can’t wait for someone with a mental illness to die by suicide and then argue the inmate shouldn’t have been in their jail in the first place. Since most sheriffs understand they’re the largest mental health provider in many communities, Hayes argues they need to act like it.

“That’s when you separate the proactive sheriffs from the reactive sheriffs,” he said. “I don’t have sympathy for those who sit on the problem and don’t advocate for a solution.”

While jails need to improve suicide prevention, others say more needs to be done in the health care and public health sectors to treat mental illness and prevent people from getting to the place where law enforcement gets involved.

“We need to be thinking way more critically, beyond the point that a person is going to hit jail,” the Vera Institute’s Cloud said. “The fact that we rely on the criminal justice system to put people in jail until we figure out what to do with them is really the problematic part.”

During the course of the next year, OPB, KUOW and the Northwest News Network are teaming up to report on the epidemic of deaths at Northwest jails in our ongoing series “Booked and Buried.” If you have a tip or a story idea, email us.

Copyright 2019 Oregon Public Broadcasting. To see more, visit opb.org

Related Stories:

Federal funding cuts, freezes hit Palouse nonprofits

Palouse area nonprofits focused on helping with emergency food and the arts have had their funding frozen or cut.

Why affordable housing providers say they’re facing an ‘existential’ crisis

Affordable housing providers across the Northwest have been contending with rising insurance premiums — and, in some cases, getting kicked off their plans altogether.

Pacific Northwest author’s new novel captures atmosphere of the region

On a gray, early spring morning, I drove to Steilacoom, Washington, to catch the ferry to Anderson Island. I boarded alongside the line of other cars and after parking, stepped out onto the deck of the boat. The ferry pushed off from the dock and rocked a little in the Puget Sound before steadying.

I took this journey to the real Anderson Island to see from the water what inspired Northwest author Kirsten Sundberg Lunstrum’s new novel, “Elita,” which was published earlier this year. Sundberg Lunstrum was inspired while sailing around the Puget Sound to write a mystery novel on an island.

Sundberg Lunstrum read excerpts of the book at a gathering at Tacoma’s Grit City Books.