Fresh Air: New Janis Joplin Biography Reveals The Hard Work Behind The Heart

LISTEN

BY TERRY GROSS

In the 1960s, Janis Joplin was an icon of the counterculture, a female rock star at a time when rock was an all-boys’ club.

“At that point in time there weren’t too many women taking center stage,” biographer Holly George-Warren says. “Janis created this incredible image that went along with her amazing vocal ability. … [She] was very, very different than most of the women that came before.”

On stage, Joplin oozed confidence, sexuality and exuberance. It all seemed so effortless, but George-Warren describes Joplin as a bookworm who worked hard to create her “blues feelin’ mama” musical persona.

“She was a real scholar of music. … She didn’t want people to know how hard she worked,” George-Warren says. “She wanted people to think she was just this vessel, or this megaphone, or something that was just up there on stage, and the music and emotions were just coming out of her.”

George-Warren says she decided to write about Joplin after listening to tapes from the Columbia Records vault of the singer’s recording session with producer Paul Rothchild for the album Pearl. (The album was released posthumously in 1971, following Joplin’s fatal overdose in 1970.)

“Rothchild [is] known for being this very authoritarian producer, but … Janis was just coming up with idea after idea,” George-Warren says. “She was basically co-producing this record with him. And that turned my head around. … I realized that that part of her story had not been told.”

George-Warren’s new biography is Janis.

Interview highlights

On Janis Joplin as a live performer

What made Janis really different as a live performer is that she connected with her audiences by tapping into her deepest feelings. And there was this authenticity that came across. She wasn’t just standing up there singing — she was basically emptying out her guts through that amazing voice of hers, and touching her audience members like they had never been touched before. I’ve talked to people who saw her back in 1966, ’67 and they talk about it as if it was yesterday — especially women, I think, because she was able to express deep-down emotions, shame, disappointments, hurts that I think a lot of women in her audience couldn’t express themselves. And Janis was not only just singing to them; she was singing for them. And I think that kind of deep connection was very, very unique at that time.

On the sexual energy she exuded onstage

You can look to two major influences that Janis had that I think affected her sexuality and the way she expressed it onstage. One was, of course, the great Bessie Smith, whose lyrics Janis knew by heart. … She started performing Bessie Smith songs around 1963, and those kind of lyrics of sexuality, of sexual longing, sexual betrayal: Those very much informed Janis’ own songwriting and the songs that she chose to sing.

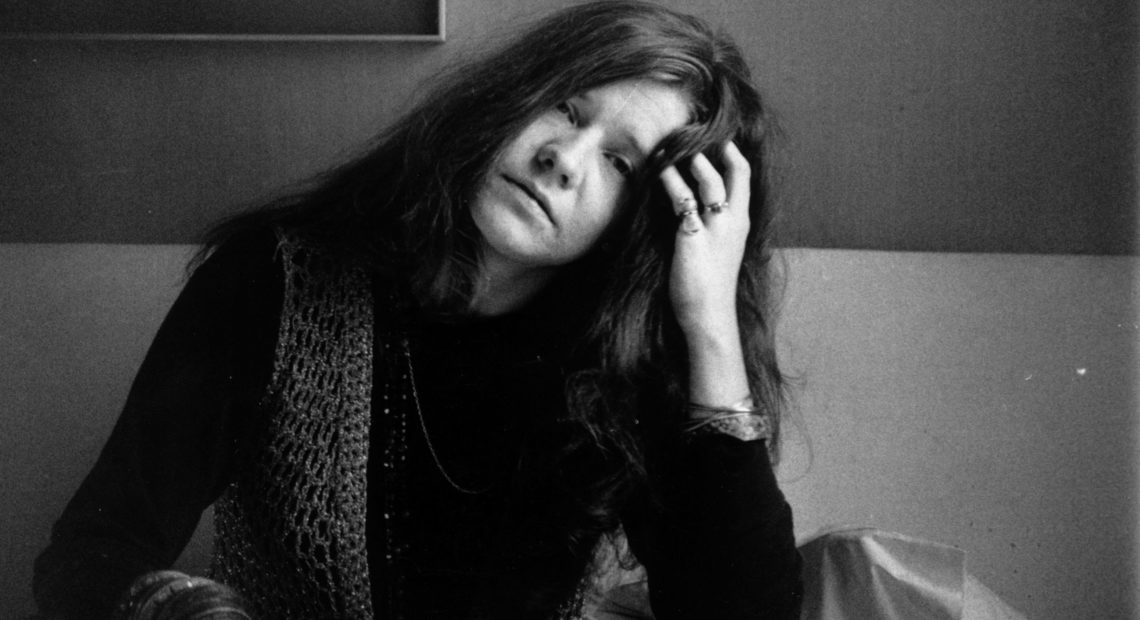

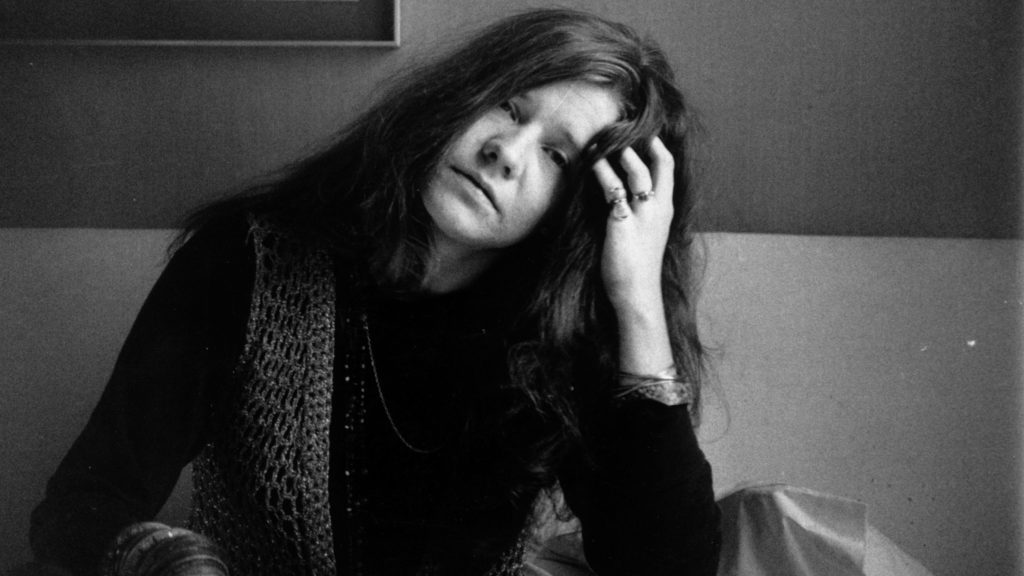

Biographer Holly George-Warren describes rock star Janis Joplin (shown here in 1969) as an introspective person who didn’t always like her own thoughts. CREDIT: Evening Standard/Getty Images

The other major influence was Otis Redding. She was a huge Otis fan until the day she died, and she got to see him perform live three nights in a row at the Fillmore back in 1966, and it transformed her. He was a very sexual performer and he was able to emit this heat on stage that Janis herself was able to do through her own way of manifesting these feelings that she had while singing these songs. Janis … compared singing on stage to having an orgasm. She blew some journalists’ minds when she used that expression, but it was a very sexual experience for her.

On the black artists that influenced her sound

Janis took her own vocals for granted until she discovered Lead Belly. She just thought: Oh, anybody can sing soprano. She sang in the church choir and the glee club. But when she heard Lead Belly’s voice, she wanted to experiment with roughing up her sound and making it more raw and she was a mimic. She discovered Odetta, who had kind of the round tones, and she started trying to sing like Odetta on her records. But she was mostly inspired by Lead Belly, until she discovered, of course, Bessie Smith, and then that was all she wrote.

On the sexism she faced in the music industry

Once she was a public figure, the press would, of course, be amazed by her vocals, and critics would be talking about what a great singer she was. But they were often singling out her body parts and talking about her physical appearance in a way that, of course, male singers, rock singers, were really not getting that kind of attention from the press.

Also, she really had to bust down barriers to be able to have control, to do what she wanted to do, because she loved being in Big Brother and the Holding Company, for example — the band with whom she catapulted to fame — but she was such a restless spirit as far as a musician goes. She wanted to keep exploring different sounds, different kinds of music, and when she did that, it was really awful in that the boys’ club of music critics just kind of raked over the coals for dropping her band and going off on her own, and they tried to say she was selling out and going showbiz.

On how Joplin’s experience with the “kozmic blues” connected with her alcohol use

She was an introspective person deep down, and she didn’t like her thoughts. She was a fatalist. She had learned this kind of existential, dark philosophy from her father, who called it the “Saturday night swindle,” which was basically the idea that no matter how hard you work, how much you try to achieve your goals, you’re never really going to be happy. There’s always going to be a let-down. There’s always going to be disappointments — which was [a] pretty dark attitude when you think about that whole ’50s positivism etc., post-World War II America. Janis called this idea the “kozmic blues,” and it really did dog her.

I think between that philosophy and all the pressures of leading a band, being in the spotlight, being a star, having to always live up to her image night after night on stage and, of course, in the recording studio, she wanted something that was going to numb those kind of feelings of anxiety and fear. … She started drinking when she was a teenager. So early on, she realized that if something can kind of take you away from yourself, take you out of your head, it could be a good thing.

On Joplin’s addiction to heroin

Janis started turning to heroin as a way to just kind of numb herself from all the pressures and the fear of what it was like being a solo artist at that point [in] time in her career. Again, she was still very much a focal point of media. There was articles about her all the time and she had developed this whole hard-drinking blues mama image that she had. So this was a secret vice of hers that she picked up. Unfortunately, heroin was pretty prevalent. No one really realized at the time, and so she gradually got addicted to heroin in 1969. …

She tried to kick heroin a few times. She finally did almost for good in 1970, right about the time she had put together a new band which became called Full Tilt Boogie Band. And she got off heroin for a while actually by going to Brazil for Carnival, and I mean — it’s so hard to believe that she was a massive rock star, but she was hitchhiking around in Brazil for a while, totally cleaned up, really loved the feeling of being clean and back to her old self again.

Sadly, she relapsed when she got back to California, and then finally she quit in the spring of 1970 and she stayed off of it for about four or five months, until tragically she relapsed again while recording Pearl in Los Angeles, got a very strong dose. … It was much more pure than she had ever used before, and her tolerance was down. She was by herself, overdosed and died on Oct. 4, 1970. … A lot of musicians were using that drug and people didn’t realize it. But when Janis overdosed on heroin, I think it was a wake-up call — but soon sadly forgotten.

Lauren Krenzel and Seth Kelley produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Patrick Jarenwattananon adapted it for the Web.

9(MDAyOTk4OTc0MDEyNzcxNDIzMTZjM2E3Zg004))