In ‘Stolen,’ Five Boys Are Caught In A Reverse Underground Railroad Toward Slavery

BY ILANA MASAD

In the second episode of 1619, journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones’ New York Times-produced podcast, she interviews sociologist Matthew Desmond about the ways in which the institution of slavery in the United States both drove and was driven by economic concerns.

“[M]any of our depictions of the cotton plantation are bucolic and small,” Desmond says at one point. “[Y]ou might see a handful of enslaved workers in the fields, and an overseer on a horse, and then the owner in a big house. That’s not how it was. It was incredibly complex… [C]omplex hierarchies with mid-level managers… Complicated workforce supervision techniques were developed… Professional manuals and credentials were developed… But behind all the sophistication, behind all this capitalistic rationality, was violence.”

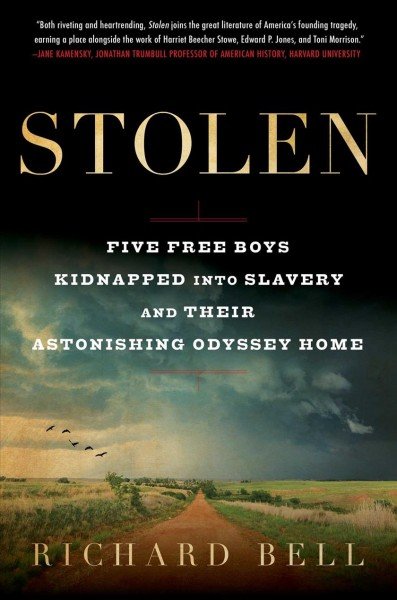

‘Stolen: Five Free Boys Kidnapped into Slavery and Their Astonishing Odyssey Home’ by Richard Bell

Indeed, slavery wasn’t an institution driven solely by cruelty — although it was unendingly cruel and surely some of its enforcers relished its violent backbone — but by money. The sophistication Desmond speaks of was made possible, of course, by the law, which until the Thirteenth Amendment, allowed for the trade in human beings. The legal aspects of the institution, as well as the mental gymnastics surrounding what was illegal under the same laws, create a deeply unnerving undercurrent throughout early American history scholar Richard Bell’s new book, Stolen: Five Free Boys Kidnapped into Slavery and Their Astonishing Odyssey Home.

Meticulously researched — the footnotes take up about a sixth of the book, and are worth looking at — Bell’s narrative follows the kidnapping of five black boys from Philadelphia in August 1825. Four of the children had been raised free: Enos Tilghman, 10; Alex Manlove, 8; Joe Johnson, 14 or 15; and Cornelius Sinclair, 10. The fifth boy, Sam Scomp, also 15, was a new arrival in Philadelphia, having recently run away from one of the last slaveholding plantations in New Jersey, where many of his family members remained. While the four other boys knew to be wary of white men taking too much of an interest in them, they and Sam all trusted the brown man calling himself John Smith who offered them easy work for more pay than they’d normally get for it. But the mixed-race John Purnell, which was the man’s real name, was employed by an expansive interstate kidnapping crew run by Joseph Johnson. And as soon as the boys arrived on the ship that supposedly held fruit for them to unload, they were ambushed, chained, and locked in the hold.

This kidnapping was not an outstanding or rare occurrence. Even as the Underground Railroad ferried enslaved people running north towards freedom, Bell writes that “[o]n the Reverse Underground Railroad, free black people vanished from northern cities like Philadelphia and were made to trudge southward and westward to be sold into plantation slavery.” We hear less about this horrendous practice than we do about its inverse, but it was rampant, and the “volume of traffic on the two railroads was roughly the same.”

After 1808, when the importation of foreign-born humans was outlawed in the United States, the domestic slave trade — which was still legal — saw a boom, and like any business legitimate in the eyes of the law, it had its black market, which was where the snatching of children away from hearth, home, and freedom came in.

The great, outrageous irony of Bell’s book is just how the children, made to march south along with two women, managed to return home. Southern plantation owners relied on the legality of the slave trade in order to make their money; in order to retain this shiny legitimacy, they claimed to want no part in the illegal trade in kidnapped people, although there was clearly a market for cheaper options in the purchasing of human bodies for their wombs and labor.

Yet in order to retain their law-abiding status, several prominent southerners played integral roles in securing these kidnapped children’s freedom. One of them, Mississippi’s attorney general Richard Stockton, wrote that while slavery was legal in the state, no one held “in greater abhorrence” the illegal trafficking in stolen people. “This calculated antipathy for child snatchers,” Bell writes, “had the great benefit of deflecting the attention of anti-slavery activists in the North away from the far larger legal slave trade between the Upper South and the Cotton Kingdom.”

Stolen is a remarkable narrative, in part, because of how Bell manages to clearly relate the complex politics of the time without ever legitimizing the choices made by those who bought and sold human lives. It’s also wonderful for the ways in which Bell infuses each stage of the children’s harrowing ordeal with empathy, focusing in on what they might have been feeling, drawing either from the precious little that remains of their own voices or from contemporary accounts of similarly traumatic kidnappings.

In telling as full a story as he can, Bell gives voice to the broader implications of this episode while not losing sight of all that is specific and singular about Tilghman, Manlove, Johnson, Sinclair, and Scomp’s experiences.

Ilana Masad is an Israeli American fiction writer, critic and founder/host of the podcast The Other Stories. Her debut novel, All My Mother’s Lovers, is forthcoming from Dutton in 2020.