Pumping Oxygen In A Lake To Try To Save Fish Facing Climate Change

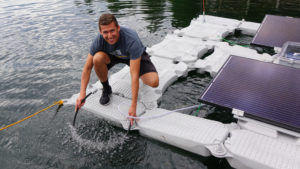

PHOTO: Mohammed Bawazeer and Ian Riley carry a battery that will power the aeration system on Upper Klamath Lake for 32 hours, even if the sun isn’t shining. CREDIT: Jes Burns/OPB

You’d never suspect it on a whisper-still morning, with the mountains and marsh reflecting off the water, but Upper Klamath Lake in southern Oregon is a tough place to be a fish.

The shortnose and Lost River suckers provide a case in point. The two species of fish, which look like a big-lipped cross between a carp and cod, used to be common in this lake. For millennia, they were an important traditional food source for the local tribes. The federal government considers them endangered species.

There’s a population of long-lived adult suckers hanging on and continuing to reproduce, but virtually none of their offspring are surviving for longer than a year.

“The juvenile sucker, they’re dying off. They’re not recruiting new adults,” says Mason Terry, a renewable energy professor at the Oregon Institute of Technology in Klamath Falls.

Poor water quality — exacerbated by the warming climate — is considered a significant cause of the sucker death. One key problem for the Upper Klamath is a low dissolved oxygen issue called hypoxia.

Fish breathe oxygen out of the water, and the oxygen levels here can drop extremely low, especially in late summer. That coincides with the time juvenile suckers appear to just vanish from the lake.

When Terry learned that low oxygen levels were one of the suspected reasons the endangered suckers aren’t surviving into adulthood, he had an idea.

“I thought, Why don’t we do what they do in fish ponds or in your aquarium? Why don’t we just try and bubble some air down in there and see what happens?” he says. “See if there’s just a little boost to affect this one factor that might be a cause of their mortality.”

Like a giant aquarium bubbler

Terry’s renewable energy students at OIT drag a floating solar panel raft — about as large as a single-car garage — out of the lake and onto the Rocky Point boat landing on the northwest side of the large, shallow lake.

This is the final assembly site for a solar-powered aeration system designed by Terry.

Ian Riley and classmate Mohammed Bawazeer walk it over to a plastic dry box that protects all the electrical components of the system from the elements.

Four 310-watt panels run two compressors that would push air — with all the oxygen it contains — down into the lake. Any power left over would go to charge the batteries, which are designed to power the compressors for 32 hours without sun.

Jennifer Berdyugin is coordinating the project, and checks that all the components are hooked up.

“All that’s left to do is turn on the pump and then make sure that it’s bubbling the water,” she says. “So, really, the telltale will be, ‘Are there bubbles or not?'”

The renewable energy students drag the solar raft back into the lake, and with the push of a button the compressor came to life. The air hose turns into an underwater sparkler as air is pushed through thousands of tiny holes.

Oregon Institute of Technology student Juan Billarreal holds the aeration hose that will add dissolved oxygen to Upper Klamath Lake. CREDIT: Jes Burns/OPB

“Bubble, bubble!” Riley calls across the noise as another student claps in celebration.

The team has assembled two rafts that are currently anchored at a site on the lake where juvenile suckers have been found to gather.

“It’s a way to provide an area for the suckers to get out of the bad water quality and at least have somewhere to hide until things get better,” says U.S. Fish and Wildlife biologist Josh Rasmussen, who works on sucker conservation in the Klamath Basin.

Aerated future

The chemistry of lakes worldwide has been altered by human development and agriculture. Ken Ashley, a lake aeration specialist at the British Columbia Institute of Technology, says the problems are only going to get worse with climate change.

“As the climate gets warmer and lakes are stratified longer, then the effects of the low oxygen are going to get magnified and there’s going to be more algal problems, and more fish kills, and more taste and odor problems,” he says. “And there’ll be more demand to do something about it.”

When the temperature of water on the surface rises, it prevents oxygen from getting to lake bottoms. Aeration can be a solution.

“It’s a growth industry, unfortunately,” he says.

One challenge at Upper Klamath Lake is that it’s really big, the largest freshwater lake in Oregon. A pinpoint or two of aeration floating in a hundred-square-mile lake won’t be the ultimate answer. But it could help conditions immediately around the rafts.

OIT’s Terry says preliminary measures show oxygen levels in the vicinity of the rafts have improved. The Klamath Tribes are monitoring the systems. And next year, Terry will use the information they collect to tweak and launch two more solar aeration systems.

But the success of this project won’t ultimately be known until the next fish counts reveal whether any Upper Klamath Lake suckers survive past their first birthday.

9(MDAyOTk4OTc0MDEyNzcxNDIzMTZjM2E3Zg004))