Yakama And Lummi Nation Leaders Call For Removal Of 3 Lower Columbia River Dams

Read On

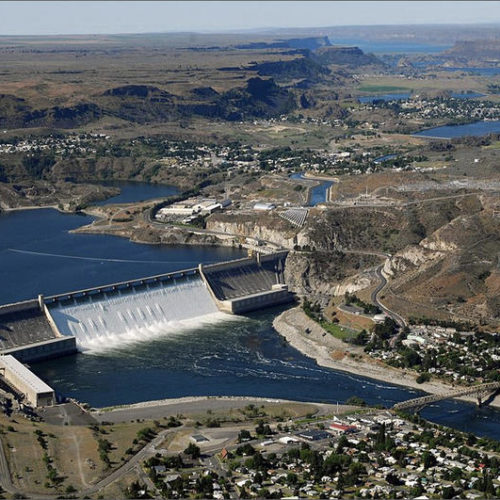

The Yakama Nation is calling for the removal of three lower Columbia River dams — Bonneville, The Dalles and John Day — in an effort to save salmon and preserve First Nations’ culture.

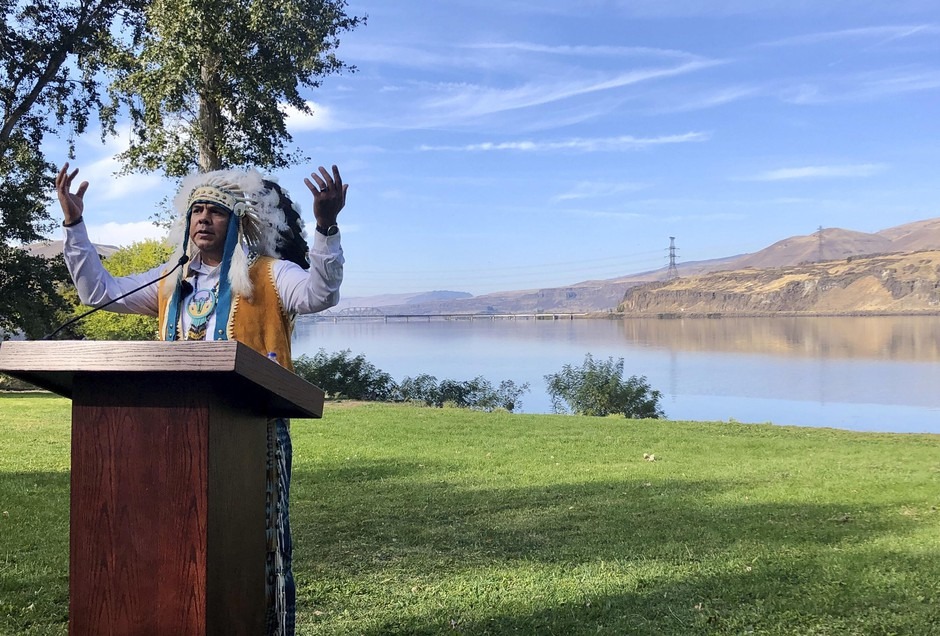

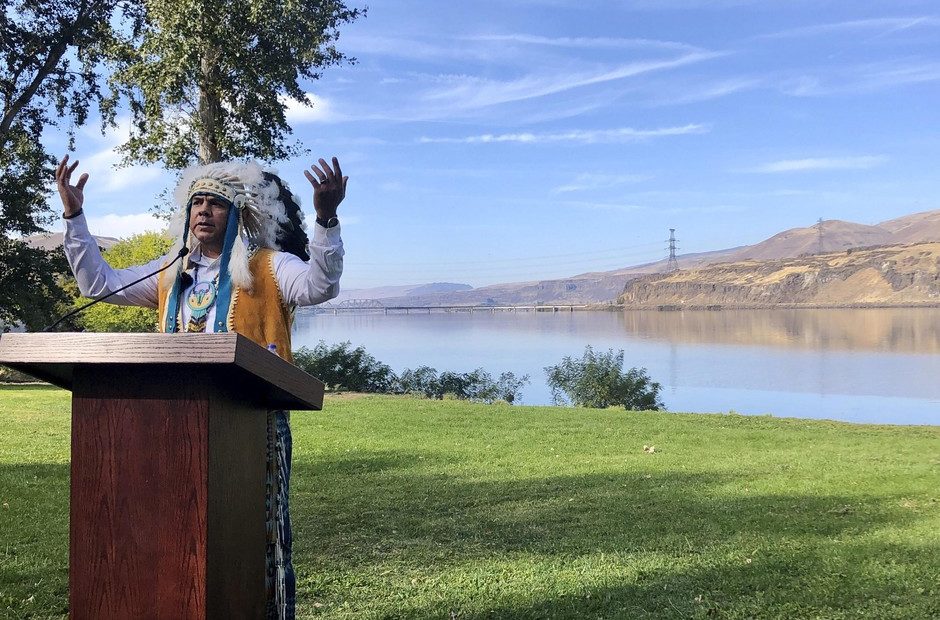

Standing on the banks of the Columbia River Monday, near the remnants of Celilo Falls, Yakama Nation Chairman JoDe Goudy traced the history of decrees, congressional acts and court cases that led to the damming of the river.

“The false religious doctrine of Christian discovery was used by the United States to perpetuate crimes of genocide and forced displacement against Native Peoples,” Goudy said. “The Columbia River dams were built on this false legal foundation, and decimated the Yakama Nation’s fisheries, traditional foods and cultural sites.”

This Indigenous Peoples’ Day, Goudy looked to the river behind him, now a lake, he said.

“We are calling on that action to happen, because when you go back, and you understand the truth, with regard to what has materialized – this lake behind us all – once one of the greatest, one of the mightiest big rivers in the world,” Goudy said.

Celilo Falls once served as an integral fishing location for Northwest tribes, and was reputed to be one of the most productive fisheries in the world. The falls were submerged when The Dalles Dam was built in 1957. The final dam on the Columbia River, John Day Dam, was completed in 1972.

“Our way of life, of the Natives, is fading. What we can collectively do to sustain our way of life from now to as far as we can see into the future because if we do not, then we will cease to be,” Goudy said.

Goudy said First Nations never agreed to damming the river. He called on congressional leaders and others to remove the dams, and now have a “chance to do what’s right.”

Lummi Nation Chairman Jay Julius said the fate of salmon today is a “horrifying reality.”

“A stand was taken again today. As our elders took yesterday. As our ancestors took yesterday,” Julius said.

Although calls to remove the four lower Snake River dams have been ongoing, this is the first big push to remove these mainstream Columbia River dams.

The dams are managed by the Bonneville Power Administration. They provide power and river access to inland ports.

In a statement, Northwest RiverPartners, a group that advocates for ports and businesses, said the dams provide critical carbon-free power.

“We have great respect for the Yakama and Lummi nations and for Indigenous Peoples’ Day, but we believe that the lower Columbia River dams are a critical carbon free resource in our fight against the climate crisis that threatens the health and well-being of the entire Northwest,” the emailed statement said.

Conservation groups called the proposal “bold and courageous,” especially as it comes to restoring threatened and endangered salmon and endangered orcas that rely on those same fish.

“Our decades-long effort to recover endangered salmon is not working. The stagnant reservoirs behind the dams create dangerously hot water, and climate change is pushing the river over the edge. Year after year, the river gets hotter. The system is broken, but we can fix it,” said Brett VandenHeuvel, with Columbia Riverkeeper, in a statement.

At the event, people shared childhood memories of a time before Celilo Falls was submerged.

“They say that you could walk across the water and walk across the fish. This whole Columbia River has been covered. I remember when John Day Dam was made. I remember being out in that river fishing, and I remember an island, where we once made arrowheads, that were covered up,” said Karen Jim Whitford, a Yakama elder

Klickitat tribal elder Wilbur Slockish, Jr., pointed to recent dam removals in the Northwest and how quickly fish have returned to those rivers.

“Take a look at Condit Dam, how the river is rebuilding it. Take a look at Lower Elwha, what the fish are doing there, and maybe we’ll get those spawning beds back up below John Day (Dam),” Slockish said. “All the dams need to go.”

First Nation leaders said the dams need to be removed as soon as possible to save salmon.

“Will we be the generation that forgot those that are coming behind us – those that remain unborn? Will we be the generation that forgot to speak for the resources that cannot speak in a manner that we can understand,” Goudy said.

UPDATE, 10/15/19, 10:50 AM: This article has been updated to include the names of the dams at the top of the article.

Copyright 2019 Northwest Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

Tribes Team With Northwest Researchers To Show Viability Of Salmon Above Upper Columbia Dams

The Upper Columbia United Tribes are working together to prove salmon can be reintroduced – and can survive – in the waters above Grand Coulee.

Report Lays Out Bleak Picture For Northwest Salmon ‘Teetering On The Brink Of Extinction’

Washington’s salmon are “teetering on the brink of extinction,” according to a new report. It says the state must change how it’s responding to climate change and the growing number of people in Washington.

Federal Decision To Keep Snake River Dams In Place Is Now Official. Controversy Far From Over

After four years of study, the Record of Decision makes the federal agencies’ preferred option official. Managers and dam supporters say it will benefit salmon, reliable hydropower and the economy. Wild salmon advocates, tribal representatives and renewable energy advocates say this decision will hurt salmon and the orcas that depend on them for food.