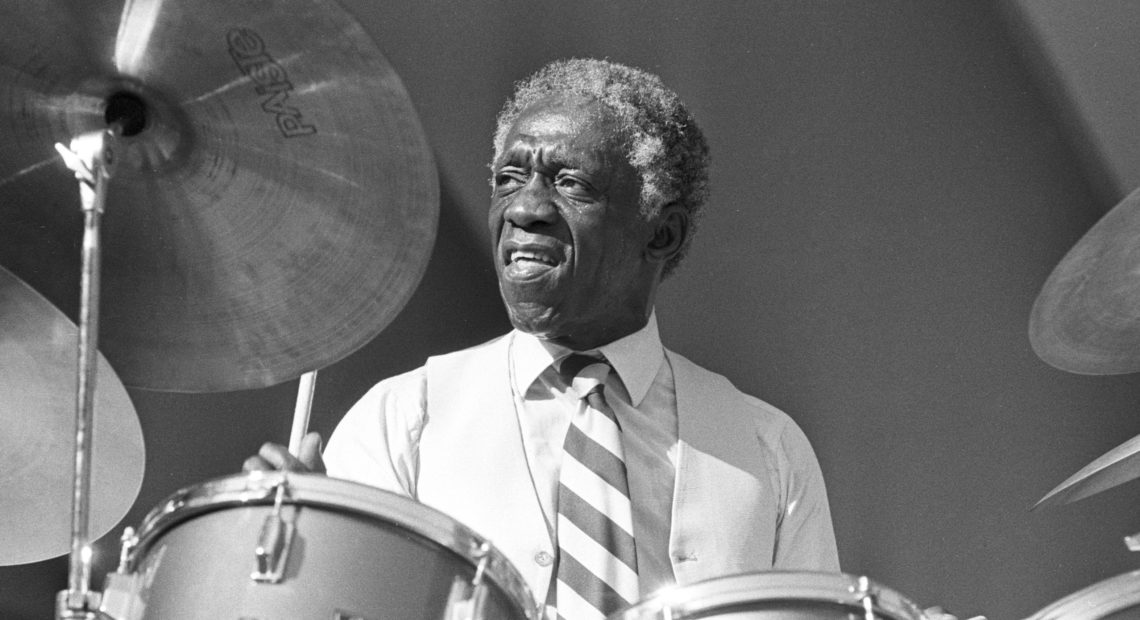

Art Blakey’s Jazz Legacy: A Rallying Cry And A Gathering Place

LISTEN

BY TOM VITALE

Art Blakey was born 100 years ago, on Oct. 11, 1919, and America’s homegrown music — jazz — might not sound quite like it does today if it weren’t for the influence of the late drummer.

“I would call Art Blakey’s music the spine of the jazz tradition post-World War II,” Giovanni Russonello, a music critic for The New York Times, says. According to Russonello, Blakey’s rhythmic groove set the pace for jazz in the second half of the 20th century. “He was playing music that was meant to pull people together, and that was why I think he became such a great mentor, such a great carrier of the tradition and passing on of the tradition. That beat was magnetic. That beat was a rallying cry [and] it was also a gathering place.”

That gathering place became his group, the Jazz Messengers, founded in 1954 with pianist Horace Silver. From the beginning, he sought out talented young musicians and encouraged them to compose for the group. It came to be called “Blakey’s University.”

Blakey himself learned from his elders. He grew up in Pittsburgh and was playing in jazz clubs as a teenager while working in steel mills during the day. In his 20s, the drummer made a name for himself with some of the biggest big bands and the early beboppers before passing on his knowledge to the next generation.

“[Young musicians need] someplace to hone their arts,” Blakey told me in 1986, between sets at the Sweet Basil jazz club in Greenwich Village. “All musicians of my time should be … nurturing the young cats. Let ’em play. Let ’em come along, because that’s the only way the art form is going to live. And [jazz] is the only art form America has.”

Wayne Shorter, who went on to become one of the most respected composers and saxophonists in jazz, was 26 years old when he joined The Jazz Messengers in 1959. Blakey’s advice to Shorter and all the “students” of Blakey’s University — future stars such as Lee Morgan, Donald Byrd, Clifford Brown and Terence Blanchard — was to “never overplay and don’t short [change] your audience,” Shorter says.

“He gave us a lot of room to grow, all the time. He wanted us to try things,” Terence Blanchard, who was only 19 years old and a trumpet student at Rutgers University when he replaced Wynton Marsalis in 1982, says. “He would tell us, ‘Don’t rest on what [you] did in the past. You guys have to create your own vision and your own sound with this group.’ ”

Blanchard went on to lead his own bands and compose music for Spike Lee’s films. In four years with Blakey’s band, Blanchard says he learned as much from the drummer off the bandstand as he did on it, with Blakey’s humility, in particular, leaving a mark.

“He said, ‘This is about music. It’s about washing away the dust of everyday life for people who have been working all day and want to get away,’ ” recalls Blanchard. To make ” ‘a moment in time where they could be divorced away from all the trials and tribulations of the day.’ That’s what he used to talk to us about — about the importance of being an artist [and] what our role is in society.”

And that role was making art that inspired, as Art Blakey said in 1986.

“You can’t just think about making money. Because you ain’t never going to see an armored car following a hearse. The only thing that follows you to the cemetery is respect. And you must earn it. So that’s where I’m at: I chose respect.”

Art Blakey died in 1990 at the age of 71. As for respect, from the musicians in his bands and from his audience: He earned it.