Versatile, Smudgy, Suitable For Women? Exhibition Traces The History Of Pastels

LISTEN

BY SUSAN STAMBERG

Many people may think of pastels as a medium for kids in art class. But at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the “Touch of Color” exhibition celebrates the history of pastel from the Renaissance to the modern day.

These works of art are hard to exhibit — “They’re very rarely loaned from other museums or to other museums because the medium is so delicate,” explains National Gallery Director Kaywin Feldman.

An exhibition of 64 pastel works of art are now on view at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. Pastels are fragile, and therefore a challenge to display. Above, Edgar Degas’ Café-Concert, which he drew in 1876-77. CREDIT: National Gallery of Art

But artists liked working with them, in part because they were adaptable. An artist commissioned to paint an oil portrait would have to have the subject come to the studio, explains former Washington Post art critic Paul Richard. “You had to have stinky solvents around so you could clean your brushes. You had to wait ’till one little passage of the painting dried sufficiently so you could add another. Pastels are a lot easier.”

Pastels allowed artists to work quickly. And pastel sticks — a blend of colored pigment, chalk, and a binder-like gum — are easy to carry around.

But getting those powdery colors to stay in one place was the challenge. Pastels smudge. Edgar Degas — the great French pastelist (yes, it’s a noun) — fixed the colors on his ballerinas, race horses, nudes, and opera-goers with casein, a protein found in milk. Over the centuries, artists used anything (even hair spray!) to hold powdery pastel onto paper.

The sticks could produce pale colors with lots of white mixed in, or intense colors that made fabrics look rich and gorgeous. It was also perfect for depicting flawless skin, says curator Stacey Sell. “Some art historians have pointed out that some of the materials and pigments that are present in pastels were also present in human cosmetics at the time,” Sell explains.

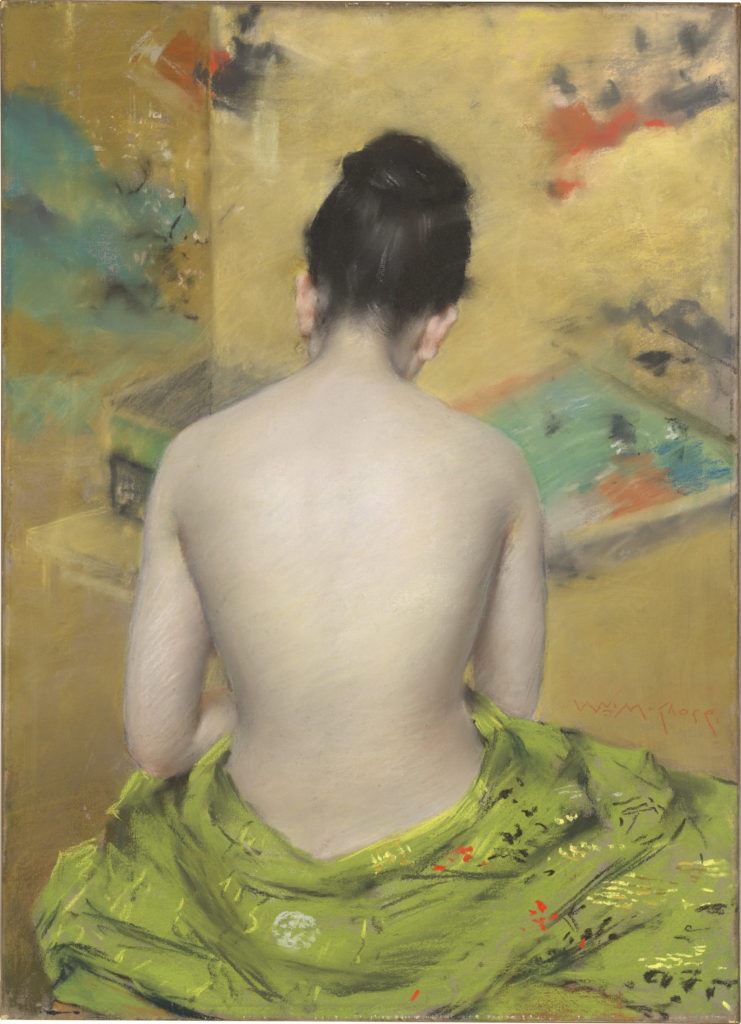

Study of Flesh Color and Gold, painted by William Merritt Chase in 1888, depicts a woman’s bare back. The skin practically glows, and it’s one of Sell’s favorites in the exhibition.

William Merritt Chase’s 1888 Study of Flesh Color and Gold, pastel on paper coated with mauve-gray grit

CREDIT: National Gallery of Art

“The mottling on this woman’s back is so beautifully subtle and it really shows off that soft, velvety texture … it’s just absolutely, seamlessly blended,” Sell says.

Chase, Degas, Manet, Matisse, and more contemporary artists like Jasper Johns were all pastel fans. Mary Cassatt and several other female artists used the chalky sticks to draw other women, often in domestic settings. Pastels were a medium once thought to be especially appropriate for women, Sell says.

“People considered it easier to learn to use than oil painting,” Sell explains. “They thought it was simpler, they considered it cleaner. There’s one theorist who said it was better for women to use because they wouldn’t soil their fair hands the way that they would with oil paint.”

Visitors may find themselves resisting the urge to reach out and touch the artworks in “The Touch of Color” exhibition. “Pastel appeals to our sense of touch in a way that no other drawing medium really does,” Sell says. “You want to reach out and touch this velvety surface — and at the same time you know that it would ruin exactly what you’re admiring.”

As French philosopher Paul Desjardins put it in 1889: “Pastel is the lightest, most fugitive of techniques — like the pollen of a lily, or the dust from a butterfly’s wing that an artist scatters and fixes on paper.”