In Central Washington, Forest Equipment Chews Through Fuel To Reduce Threat Of ‘The Next Paradise’

Listen

The trees are really dense along a stretch of bumpy, narrow road outside Cle Elum, Washington. After years of keeping fire off the landscape, the forest has grown close together.

That means there’s more fuel when a wildfire does burn through this area.

“The density of this, it’s just a wall. It’s a giant wall,” said Kyle Smith, forest manager for The Nature Conservancy of Washington.

Spinning Rod Of Metal Teeth

Forest managers are using a tool to help bring this area back to how it was 100 years ago. The tool is about the size of a tractor, with a spinning rod of metal teeth.

“If you can imagine like mowing lawn and with a sweet riding lawn mower but out in the forest, it’s something like that,” said Connor Craig, who owns Wildfire Fuel Protection. The bumper of his company rig – parked nearby – reads, “Thin it or watch it burn.”

Craig isn’t just hacking down these trees. Forest managers have a plan.

“That kind of outlines the end result. Usually we’re seeing between 200 and 350 trees per acre,” Craig said.

Land managers are using a masticator to help thin a dense forest outside Cle Elum, Washington. The masticator chews up the forest fuels with spinning metal teeth. It takes out whole trees at a time. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt/NWPB

Right now, there are between 800 and 1,000 trees per acre. They’re keeping a pattern of fire resistant trees, like ponderosa pine, Douglas fir and Western larch, sometimes called tamarack. They hope to get rid of many more grand firs, which can grow densely in shady areas.

“We’re not trying to grow trees for Weyerhaeuser here. We’re trying to restore the forest, so we want it to be more of a mosaic landscape, where we have maybe a few trees that are six feet apart and then we have a 30 foot gap,” Craig said, gesturing to an already thinned hillside behind him.

Stopping Fire

As the masticatorower gets to work chewing up the forest fuels, it’s spinning metal teeth take out whole trees at a time. It shreds branches and mulches leaves. What’s left half an hour later looks a lot like how this forest appeared a century ago.

The newly created space between trees should stop a big fire from jumping across the tops of trees (known as crowning in firefighting lingo). It should slow the fire and provide enough of a buffer to give firefighters a place to catch it before burning down to the homes below.

Connecting different projects – like these large-scale fuels management ones – with efforts by homeowners down below helps make the landscape more resilient. It’s part of a larger effort to help central Washington avoid the fate of towns like Paradise, California, which was devastated by the Camp Fire in 2018.

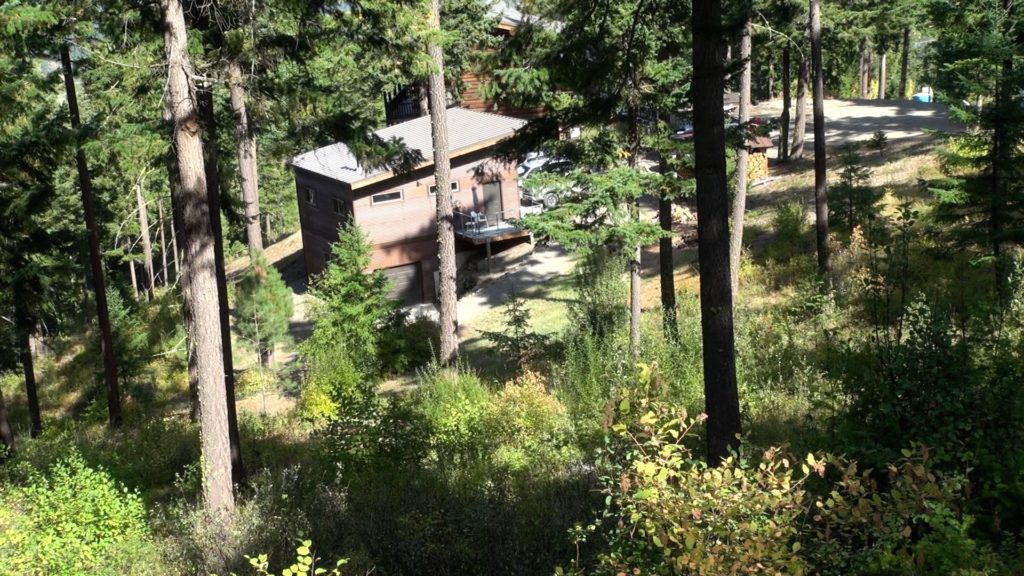

A thinned patch of forest outside of Cle Elum, Washington, has gaps and spaces between clumps of trees. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt/NWPB

“I think people look at California and think, ‘Oh good. That’s not us,’” said Reese Lolley. “It could be us.”

Reese Lolley is the director of forest restoration and fire for The Nature Conservancy in Washington. He has similar forest mastication projects planned for the other side of Interstate 90, leading into the small towns of Roslyn and Ronald.

It’s all about upping the “pace and scale” of forest restoration, Reese said. The Nature Conservancy recently identified 2.7 million acres of eastern Washington forests that need to be thinned mechanically or through prescribed fire. Washington’s Department of Natural Resources plans to thin around 1.25 million acres through a 20-year plan to improve forest health.

“It’s important that we look at how we’re treating a stand as well as how we’re connecting it in the larger landscape,” Lolley said, looking out at Cle Elum in the distance.

He said that’s especially important as climate change is predicted to increase Northwest fire risks and the length and severity of fire season.

Down the hillside, the state land managers are working with property owners to ensure their land is also more fire resilient. It’s important to connect the two landscapes, said Jason Emsley, with the state Department of Natural Resources. After all, fire doesn’t know property boundaries.

“The scale and the amount of work that needs to be done to the landscape is just so massive right now that we’re behind the ball, “Emsley said. “So we’re trying to ramp up to get back ahead of the problem eventually.”

Here in the upper Kittitas Valley, they’re thinning parts of the forest along the only gravel road in and out of this neighborhood. That should create breaks for firefighters to station themselves and help slow fires. They’re also helping property owners make sure they’re homes are prepared for when a fire strikes in this highly hazardous area.

“If just one person does work it doesn’t necessarily accomplish the task. And so all of us working together is what it’s going to take for our communities to become more fire adapted going forward.” Emsley said.

Worries About Her Property

Being fire adapted is the goal of this work along Buffalo Springs Road where six people own property and two live here full-time.

Patty O’Hearn lives here most of the year. Her 22-acre property could be the cover of a firewise magazine: metal roofs on her cabin and shed, thinned trees, mowed grasses, gravel walkways lining her home.

Patty O’Hearn’s house is prepped for when a fire burns through her hillside. It has metal roofs on her cabin and shed, thinned trees, mowed grass and gravel walkways lining her home. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt/NWPB

From the expansive view on her back porch, she saw both the 2012 Taylor Bridge and 2017 Jolly Mountain wildfires work their way toward towns and neighborhoods in the valley.

She worries about her property; it’s not a question of “if” but rather “when” a fire will burn through her hillside. O’Hearn said she’s doing what she can to help protect her land and neighbors, even if there’s more work to be done. O’Hearn has a few projects in mind.

“In particular keeping the brush under control. I’m on a steep slope, so there’s a little bit more concern for me if there were a crown fire,” she said.

Work like this is all happening now across Central Washington to help prepare the forest, homes and towns for the next fire, said The Nature Conservancy’s Reese Lolley.

“What we haven’t recognized is as much as in communities is that every individual has a role in the sense of preparing for fire before, during and after,” Lolley said.

Courtney Flatt covers environmental and natural resource issues for Northwest Public Broadcasting. She is based in Washington’s Tri-Cities. On Twitter: @courtneyflatt

Related Stories:

Federal government allocates over $6 billion to wildfire technology and management

Lawmakers are allocating over $6 billion this fiscal year to support the Department of the Interior and the United States Forest Service in wildfire response.

It’s an increase of 14% from the last year’s funding, and will support wildfire suppression, operations and a new research hub to aid fire management. This fiscal year, the forest service will see an increase of $576 million in available funding for wildfire response.

Rally Outside Board Of Natural Resources Meeting Demands Board To Address Call To Action

Hundreds gathered outside the Board of Natural Resources meeting in Olympia this week to demand the board make further commitments to forest conservation.

“Prepare For Higher Than Average Fire Season,” Says Washington Forest Protection Association

Paula Swedeen, a forest policy specialist for the Washington Environmental Council, walks through forest land adjacent to Mount Rainier National Park. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren) Listen Reporter Lauren Paterson tells