BOOK REVIEW: In ‘Here We Are,’ Heart-Rending Challenges Of Immigration Are Exposed

BY MARTHA ANNE TOLL

Aarti Namdev Shahani reports on Silicon Valley for NPR. She’s also the daughter of an immigrant who served time for a “felony.”

Her riveting memoir, Here We Are: American Dreams, American Nightmares, recounts a story of personal success against the backdrop of her family’s contorted, painful path to citizenship. Close-knit, they discovered the hard way that American justice is neither just nor colorblind.

In a bruising critique of colonialism, Shahani traces her story back to the 1947 Partition, Britain’s end to 300 years of Indian occupation. Britain’s exit strategy was to split one country into two: Hindus and Sikhs on the Indian side; Muslims on the Pakistani side. Current political upheaval in Kashmir confirms that the Partition was anything but clean; it sowed human calamity far into the future.

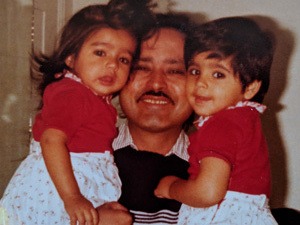

Aarti Shahani as a child with her sister and her father.

Shahani’s parents, deracinated Hindus, met at a poker party in Casablanca where everyone “had Partition in common.” They married, started a family, and encountered serious problems. Dadi, the mother of Aarti’s father Namdev, moved to Casablanca with two additional sons, one of whom was a belligerent drunk. Dadi launched a brutal attack on Aarti’s mother, whose disappointment extended beyond an abusive mother-in-law; Namdev was avoidant and retreated to drinking and smoking. Aarti’s mother attempted suicide, was rescued, and nine months later bore Aarti. Life was untenable under Dadi’s thumb (for one, she insisted Namdev sleep in her bedroom), and the Shahanis emigrated, sans grandma.

They landed in Queens in 1981, where “so many poor people from so many countries can converge, live alongside neighbors who speak different languages and pray to different gods, and yet tribal warfare does not break out,” Shahani writes. Parts of their extended family were already in Queens; others followed.

Finding an apartment was a challenge, living in it more so: America was “much harder to live in than many parts of the world.” Forty-one-year-old Namdev, with the skills to interview for a hedge fund or the foreign service, was flummoxed by cultural discomforts such as men and women mixing in public. Aarti’s mother found work sewing for a bridal shop. Despite significant obstacles, the family eked out a living, until — with the extended family’s help — Namdev and his brother Ratan opened a successful electronics store.

While his children were becoming American and Aarti blazed her way as a scholarship student through New York’s prestigious Brearley School, Namdev became one more brown-skinned victim of American justice, an unknowing two-bit player in a global drama. He and Ratan were arrested for selling watches and calculators to the Cali drug cartel.

‘Here We Are:

American Dreams, American Nightmares’ by Aarti Namdev Shahani

With a job as a secretary in a law firm, teenaged Aarti became the family lawyer. Dogged doesn’t begin to describe it. She started “chasing the skeletons in her family’s closet” and has been at it ever since.

She didn’t understand the value of a public defender, instead landing a high-end lawyer who provided inadequate representation. She investigated and inveighed, sent letters all over the city, including to the judge. Shahani later came to know the judge, whose 20/20 hindsight lends a tragic irony to the family catastrophe.

In a terrible twist of fate, Sept.11 landed in the middle of the Shahanis’ drama, with its accompanying backlash against dark-skinned immigrants. Despite the judge’s request for a sentence of community service from the prosecutor, both Uncle Ratan and Namdev were sent to Rikers. Once released, Uncle Ratan was permanently deported.

The Shahanis never gave up. Recognizing that an individual’s arrest and conviction can bring down a family, Aarti embarked on a journey of passion and zeal. She founded a nonprofit to activate families ensnared in America’s broken immigration system, concluding that racial division was “the central feature in America’s justice system.”

This story is heart-rending, but perhaps more compelling is Aarti’s struggle to understand her father. As a child, she saw him as a distant, old-world figure, out of sync with America. He was a letdown to her mother, at times more cartoonish than three-dimensional.

But as she watched him get crushed beneath the system, Aarti’s empathy was aroused. Although she burned out as an activist, she evolved as a daughter. She came to appreciate Namdev’s immigrant isolation, intensified by a conviction for acts he considered part of the normal course of business.

If you’re moved by frequent calls to deport so-called criminal or undocumented immigrants and refugees, please read Here We Are. For to “migrate to America — to cross the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans or the Sonoran Desert — is the boldest act of one’s life.” Like so many families, the Shahanis couldn’t and didn’t do everything correctly. But they worked like hell to right themselves, finally emerging from immigration limbo when President Ronald Reagan opened a pathway to a green card.

Here We Are contains multiple messages: the value of grit and hope and determination; the relentless work immigrant families undertake just to tread water; the fortitude and generosity of such families; and the gaping flaws in American justice. These messages risk going unheard, however, if readers fail to acknowledge that unless your ancestors arrived in chains or were indigenous, you, too, likely hail from immigrants who cut a few corners to survive.

Martha Anne Toll’s writing is at www.marthaannetoll.com, and she tweets at @marthaannetoll. She is the Executive Director of the Butler Family Fund.