Remembering The ‘Fast And Furious’ Music Of Composer Christopher Rouse

BY TOM HUIZENGA

Composer Christopher Rouse, who once called himself a writer of “fast and furious” music and who taught courses in the history of rock, died Saturday, Sept. 21, 2019 of complications of renal cancer at age 70.

Rouse once thought of himself as the “doom and gloom meister,” after composing a string of pieces dedicated to people who died — but not all of his music was loud, depressing, or both. In the end, he has left a body of uncompromisingly expressive works, primarily for orchestra — one of which earned him a Pulitzer Prize in 1993 — and the respect of his many students, colleagues and fans.

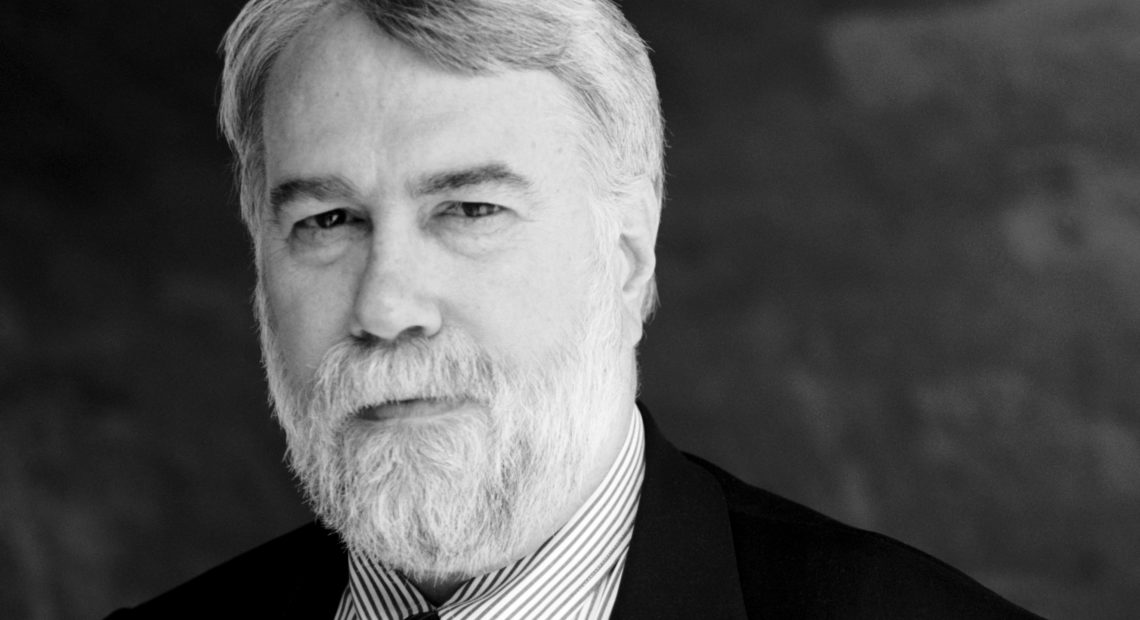

Composer Christopher Rouse, photographed in New York City in 2005. CREDIT: Jeffrey Herman/Boosey & Hawkes

“I don’t think it matters whether a piece is complex or simple, whether it’s maximalist or minimalist or tonal or atonal or whatever,” he told his publisher in a 2013 interview. “That’s not nearly as significant as whether a piece communicates something meaningful to a listener. What really matters to me the most is if people feel that connection. If they are moved, excited, if they feel consoled or angered or delighted.”

Conductor Marin Alsop and composer Nico Muhly are among the many who knew Rouse, as friends and students. They were kind enough to share some thoughts about their colleague with NPR Music.

Marin Alsop

I was able to spend time with Chris these last weeks, and he was irreverent and profound, as always. Chris had an encyclopedic knowledge of music (and many other things, too) from rock and roll and pop to many overlooked composers of the past. I loved going over to his house and chatting about all kinds of crazy music.

We reminisced recently about a recording session we had where the orchestra just couldn’t play loud enough for him. Finally, I said, “Okay, brass section. Stand up, and play right into the microphones!” Chris shouted from the booth with glee, “That’s it!” And our recording of Gorgon was born!

I first fell in love with his Trombone Concerto in the early 1990s. In memory of Leonard Bernstein, it remains one of the most difficult pieces I ever tackled. But, wow, what a payoff.

That’s how I would describe most of Chris’ music: really challenging but worth every second of the work required. I became obsessed with his music, and I think I remain the only conductor to program an all-Rouse concert. But his music is not just wild and crazy, it also grabs our hearts at the most fundamental and human core, and moves us to feel the profundity of our existence.

When I first listened to his Concerto per Corde, I admired its gnarly and mischievous qualities — and then suddenly it breaks into a Mahler-like release and I remember feeling the tears streaming down my face and thinking, “This is what music is all about!”

Chris started collecting composers’ signatures when he was a kid and amassed what I imagine is one of the largest private collections of composers’ autographs in the world. He knew how much I loved Brahms and gave me his Brahms autograph last week. Kindhearted to the end.

Nico Muhly

I first encountered Chris’ music when I was a teenager at Tanglewood. I was friends with percussionists and his pieces Ku-Ka Ilimoku and Ogoun Badagris, for percussion ensemble, were exercises in visceral teamwork, energy and power.

At first, that was the music of his I liked the best: the giant, terrifying and muscular orchestra music like Gorgon, or the skittering, dangerous force of the fast movement of the Trombone Concerto. In person and as a teacher, though, he was soft-spoken, wry, and tried to tease out of me, at least, a sense of lyricism and emotional engagement which was at the actual heart of his output. I felt vulgar, in a way, having obsessed over his fast, fortissimo music with outrageous percussion setups; the impossible and wrenching emotional journeys in pieces like Iscariot and the unapologetic slow beauty of the First Symphony are at the heart of his craft.

I remember having a strange conversation with him about Stravinsky which I think about all the time. I was saying that I found the aria “Gently Little Boat” from The Rake’s Progress unspeakably moving. He made a bearded moue of thinly veiled irritation and said that it had always left him a little bit cold – distant from the possibility of emotional engagement with the characters, the scene, and indeed, the composer.

I realized that what he was trying to impart (and a lesson which I deeply needed to learn) was that music needs to be a visceral and human reaction to tragedy and love and violence and redemption and panic and calm and humor and machine and heart, and that the composer mustn’t shy away from any of that through fussy evasive maneuvers and stylistic whitewashing.

I’d find it hard to choose any one piece by Rouse which moves me the most, but I’ve been going through the catalogue and reminding myself of the breadth of his output, all guided by this sense of personal engagement and technical mastery. All of his scores bear, under their final bars, the Latin inscription “Deo Gratias” – Thanks be to God – and I’d like to think that his legacy will be as an artist whose body of work was a kind of sacred music, wherein each piece contains a little world of struggle and gratitude.

Rouse had an insatiable appetite for music, not just classical music. At the University of Michigan, and then at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, Rouse taught a class on the history of rock music. His 1988 composition Bonham, for eight percussionists, was inspired by the late drummer for Led Zeppelin, John Bonham.

Rouse listened to early rock and roll as a kid – Little Richard and Elvis Presley. But at age six, when his mother brought him a recording of Beethoven‘s Fifth Symphony, everything changed.

“I remember I just sat down and listened to it. It was like the heavens opened up to me,” he recalled. That’s when Rouse knew he wanted to be a composer. He got turned on to more challenging sounds after convincing his mother to buy him an album that contained Prokofiev‘s Scythian Suite. “I’ll never forget, she went literally running into the kitchen and closed the door,” he said. “And that was really the beginning of my love for modern music.”

Rouse was born in Baltimore, Md., on Feb. 15, 1949. His mother was a secretary who belonged to a music appreciation club and his father worked for a postal machine company. He graduated from Cornell University and Oberlin Conservatory, studying with George Crumb and Karel Husa.

He became an orchestral composer almost by chance when, just out of grad school, working at the University of Michigan, he was given three weeks to write a five-minute piece for the school’s orchestra. The symphony orchestra has been his principal means of expression as a composer ever since.

“I became, I would honestly say, typecast as an orchestra composer, but that’s fine with me,” Rouse said. “I love writing for the orchestra. I would think I would rather write for the orchestra than anything else.”

Throughout his life Rouse said he was concerned with the human condition – and often that meant death. Musicians in the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, with whom he was closely associated in the 1980s, began calling him “Mr. Sunshine” as a joke. Rouse wrote a string of pieces inspired by the loss of friends and family. “That really had a profound effect on me and then I felt I needed to respond to it in some ways,” he said. Rouse dedicated his Pulitzer-winning Trombone Concerto to the memory of Leonard Bernstein; his Cello Concerto was written after the death of composer William Schuman; Rouse wrote his Flute Concerto after learning of the horrific death of a two-year-old boy from England who was tortured and murdered; he followed with orchestral works dedicated to the memory of composer Stephen Albert (Second Symphony) and his mother (Envoi).

Rouse later used coded language in his compositions to spell out people’s names. In 2016, he told NPR how he did it in his Third Symphony, a musical portrait of his second wife. “I have a system that I use that equates letters of the alphabet with musical pitches,” Rouse said. “And so, if I wish to spell out names or places or events or whatnot, I just take the letters of the words and convert them into musical notes.”

At several points during the symphony, Rouse’s code spells out “Natasha,” her name, over and over again. The variations on the code make up “a kind of physical portrait of her,” Rouse says. “It’s a way of setting myself kind of an artificial challenge and then seeing if I can fulfill it successfully, if I can make music out of it,” he said.

But in the end, what Rouse wanted to communicate was the emotional and expressive content in his music. “Sometimes one can write music that is just intended to be visceral, intended to be invigorating. If a listener picks up on that and feels that there is that bond established between me and them, that is what matters most.”

Rouse’s Symphony No. 6 will receive its world premiere by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Louis Langrée, on Oct. 18.