Study: Drinking Water Violations Are Higher For Communities Of Color, Including In Northwest

Read On

BY MONICA SAMAYOA / OPB

A new study on the nation’s Safe Drinking Water Act has found that low-income residents and communities of color are especially vulnerable to health-related problems because of unresolved drinking water violations.

The Natural Resources Defense Council, along with the Environmental Justice Health Alliance and Coming Clean — analyzed over 170,000 nationwide violations of the Safe Drinking Water Act that occurred from June 2016 to May 2019.

The Safe Drinking Water Act was adopted in 1974 and was supposed to ensure access to safe drinking water for all. But according to the study, the law has not been enforced equally for everyone.

In the Northwest, 16 counties were identified with the highest rate of drinking water violations and what the Centers for Disease Control considers the highest racial, ethnic, and language vulnerability.

Oregon counties on the list are Jackson, Malheur, Polk, Umatilla, Wasco, Washington and Yamhill counties. Idaho’s Cassia, Elmore, Fremont, Lincoln, Minidoka, Owyhee, Payette, and Power counties were highlighted, as was Washington’s Benton County.

The violations fall into three main categories — health-based, monitoring and reporting, and public notification.

The report says potential health effects associated with the violations include cancer, developmental effects, compromised fertility and nervous system effects.

“We are considered a green state and by having this information from this research study it’s eye-opening for many of us and many of us in positions of power to do something about it,” said Patricia Alvarado, education programs director for the Oregon nonprofit Adelante Mujeres. Its mission is to empower Latinas and the Latino community through education, enterprise and leadership training.

According to the study, the rate of drinking water violations increased in low-income and communities of color. Enforcement of safe drinking water standards was slow and inadequate for these groups, the report said.

Alvarado said it’s harder for poor and non-white people to find affordable housing. Many are afraid to speak out and report violations or complaints out of fear their landlords may retaliate.

“We have heard stories of families looking for resources and understating what does it mean to have high levels of contaminants like lead and arsenic and other contaminants and pollutants in their waters,” Alvarado said.

Alvarado said she does not want any county in Oregon to become the next Flint, Michigan.

Shawn Fleek is a spokesperson with OPAL Environmental Justice Oregon. He said the counties with the highest rate of health-based drinking water violations are predominantly rural and tribal areas.

“Infrastructure tends to be lacking in these areas due to the legacy of environmental racism, where communities of color, particularly reservations, never see equitable investment in health and safety. We must not forget that many rural Oregon communities are farming town, and many of the laborers who do that work are people of color,” said Fleek, who is Native American.

The authors of the study plan on releasing a localized interactive map, that will allow the public to learn more about the Safe Drinking Water Act violations in their region.

Copyright 2019 Oregon Public Broadcasting. To see more, visit opb.org

Related Stories:

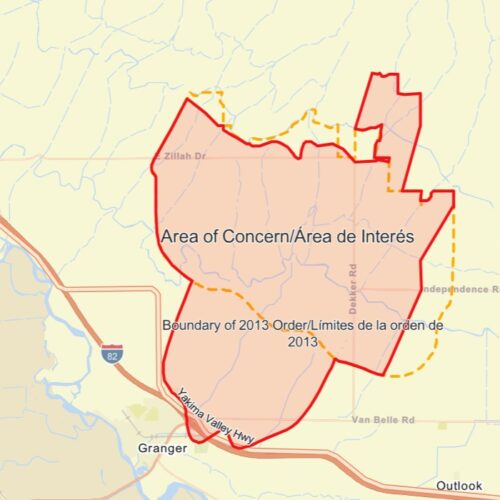

Federal judge orders Yakima County dairies to test wells, drinking water

A federal judge in Eastern Washington granted a preliminary injunction in a lawsuit that

involves over ten Yakima County dairy producers.

Elevated ‘forever chemicals’ found in Kennewick’s drinking water

The city of Kennewick has found “forever chemicals” in its drinking water. (Credit: Steve Johnson / Flickr Creative Commons) Listen (Runtime 0:53) Read The city of Kennewick has detected “forever

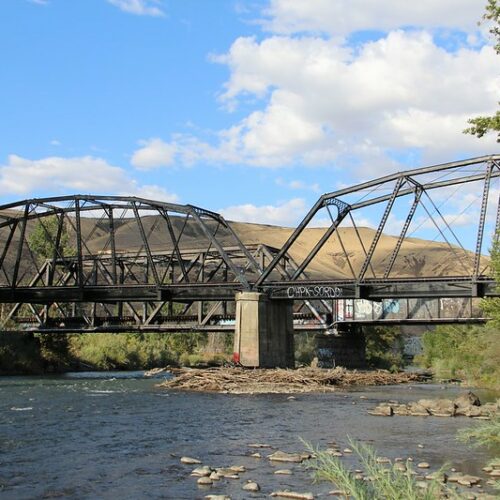

NW drinking water concerns could get worse as climate changes

The Naches River is the main source of drinking water for the City of Yakima. Credit: Cmh2315fl, Flickr Creative Commons.) Listen (Runtime 1:02) Read Thunderstorms high in the Cascades recently