This Boy Was Institutionalized At Age 12. Now He’s Moving Out — Half A Century Later

Listen

MaryAnn Brookhart remembers the day in 1964 when her parents dropped off her 12-year-old brother, Gregory Paul, at the Rainier School for the developmentally disabled in Buckley. She was 17 and had insisted on riding with them.

“They took him out of the car and sometime later they came back without him and not a word was said — ever,” Brookhart said.

From that day forward, the Rainier School would be Gregory’s home while his parents and 10 siblings lived about an hour away in Tacoma.

Initially it was traumatizing, Brookhart said. On the occasions when she would visit her brother, who was nonverbal and diagnosed with severe “mental retardation,” he seemed institutionalized and “beat up.” But over the years, Brookhart came to accept that the state-run Rainier School was where her brother belonged.

“I finally got to that place where it was the only place for him, and it was good,” Brookhart said.

By the 1970s, more than 4,000 developmentally disabled people were served in six state institutions spread across Washington, according to the Department of Social and Health Services.

Over the decades, that population fell dramatically as a national movement took hold to deinstitutionalize people with disabilities. But Gregory remained at the Rainier School. Year after year. Decade after decade.

As demand fell, institutions began to close. In the early 1990s, the state shuttered the Interlake School near Spokane. In 2011, the Frances Haddon Morgan School in Bremerton closed.

Today, most of the state’s 50,000 developmentally disabled clients live in the community. Roughly 600 of those people remain in the state’s four remaining residential habilitation centers.

Beginning in the late 1990s, after her mother died, Brookhart started visiting her brother regularly at the Rainier School from her home in University Place. Six years ago, she became his legal guardian.

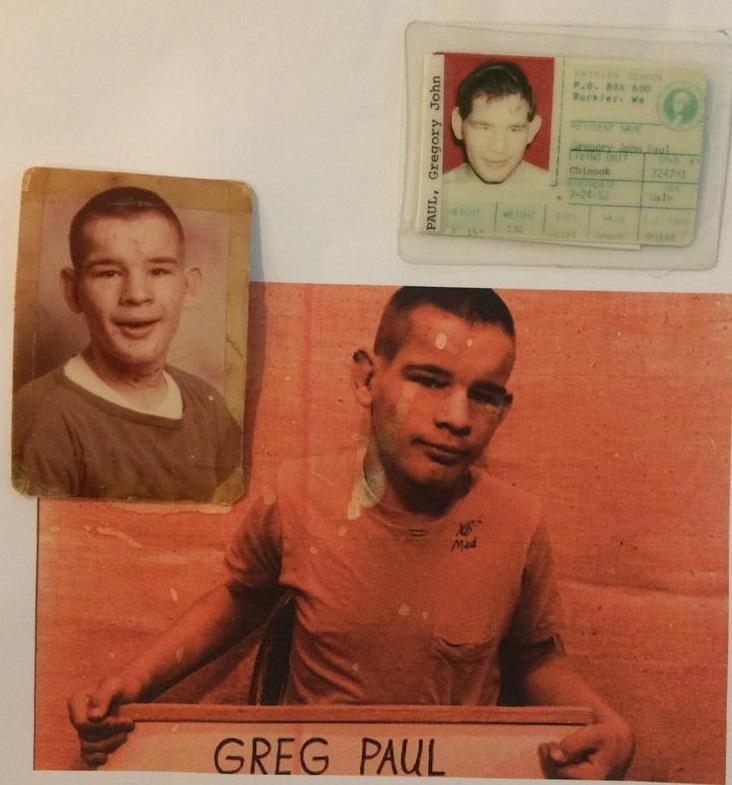

This photo montage shows Gregory Paul as a boy after he was sent to live in the Rainier School for the developmentally disabled. He moved there at age 12 and stayed 55 years. COURTESY OF MARYANN BROOKHART

And then last March, a letter arrived in the mail that would change everything.

The letter said the federal government was decertifying the unit that Gregory lived in and that he would have to relocate.

“It was absolutely so frightening,” Brookhart said.

The idea of her brother having to move after more than half a century — 55 years — at the Rainier School seemed overwhelming.

The closure of PAT A, one of three residential facilities at the Rainier School, affected 87 residents. Many of them, like Gregory, had lived there for decades. One resident had lived there 76 years.

As the weeks passed and the reality set in, Brookhart began to have a change of heart. She credits a counselor at the Rainier School, David Klingensmith, for patiently addressing the family’s fears for Gregory. Klingensmith also referred Brookhart to the Family Mentor Project, where she met other families whose loved ones had made the transition out of state institutions.

Over time, Brookhart’s sense of dread was replaced by hope for her brother.

Beginning in April, the state began moving five to 15 clients a month out of the unit that was closing at the Rainier School. About half went to state-operated nursing facilities at the Fircrest Residential Habilitation Center in Shoreline and Lakeland Village in Spokane.

The remaining residents were moved into group homes in the community. Gregory was a candidate for placement in one of those homes.

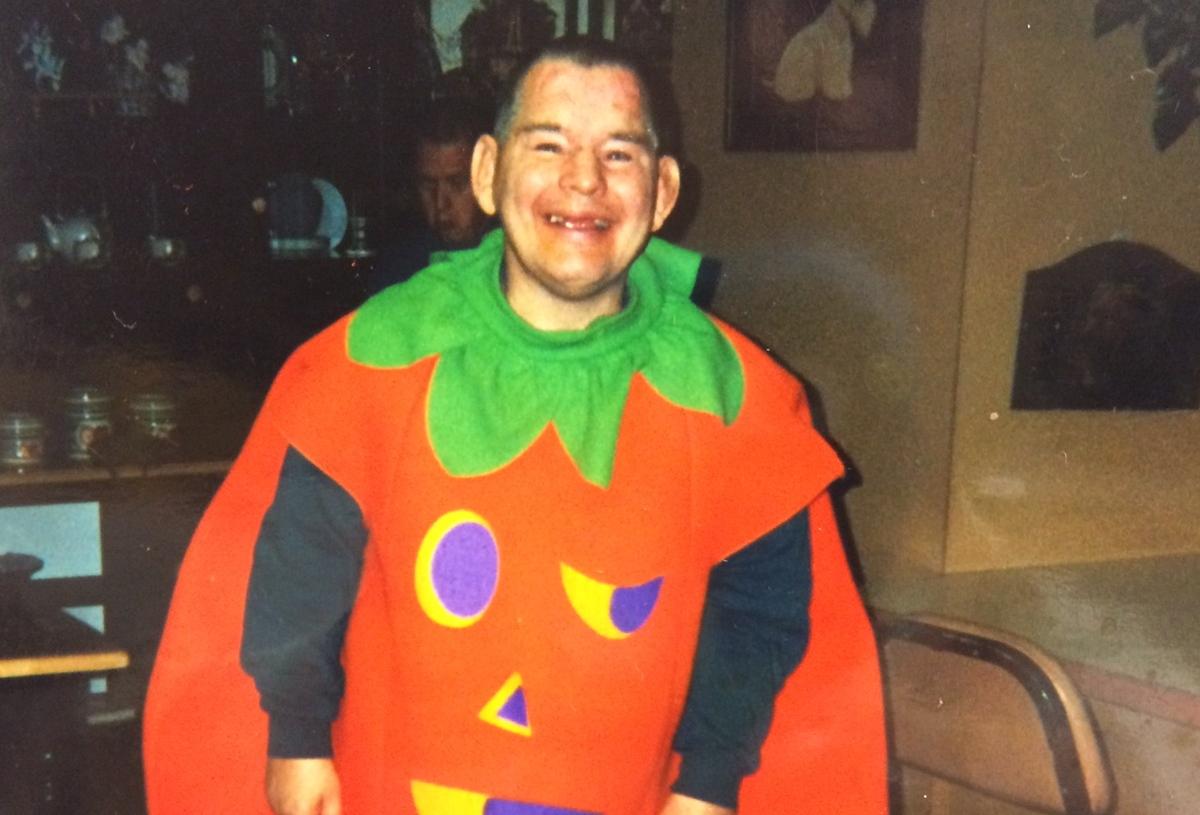

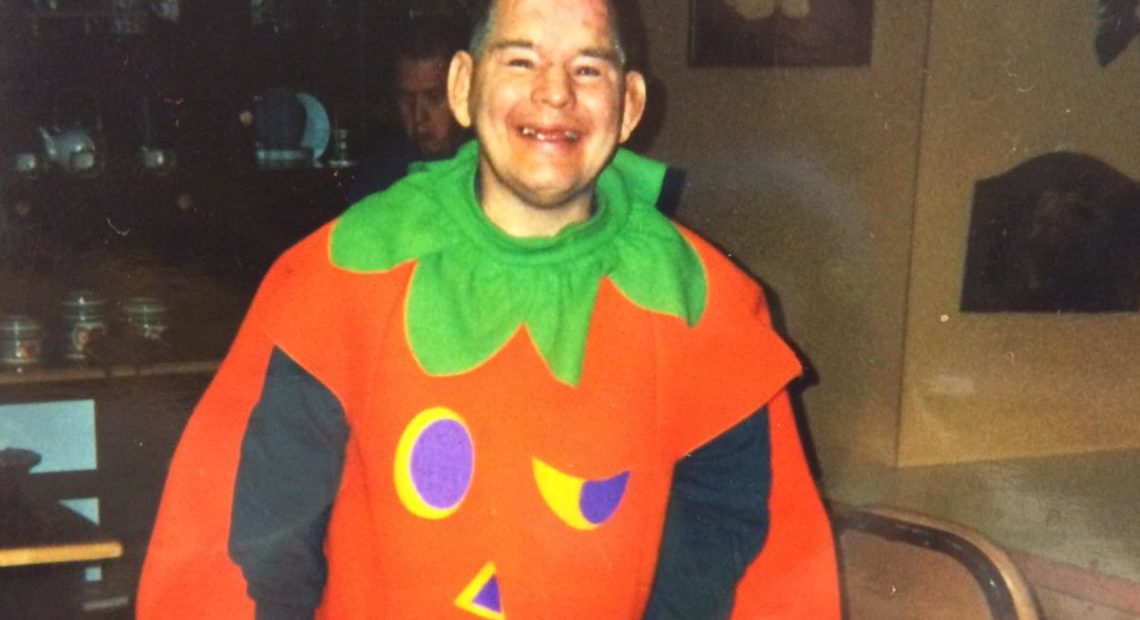

Gregory Paul is pictured with his siblings during his 65th birthday party at the Rainier School two years ago. COURTESY OF MARYANN BROOKHART

In July, the family learned where he would be going. Gregory had been assigned to a State Operated Living Alternatives home located on a golf course in Lacey, near Olympia. He would live with three other clients from the Rainier School, including his best friend. The home would be staffed around-the-clock by state employees.

After renovations were made to accommodate the special needs of the clients, Gregory and his housemates moved in earlier this month. As with any move, Brookhart said her brother had to get used to his new surroundings. But so far it’s going well — extremely well.

“I’ve been up there four times and I’m blown away how happy Greg is,” Brookhart said. “Never did I think he could make it through this huge move.”

One sign of his happiness: Brookhart said when she used to visit her brother at the Rainier School he’d use hand signals to let her know he wanted to go for a ride in the car. But now he doesn’t ask anymore. Instead, he wants to explore his new neighborhood in his wheelchair.

“It’s a miracle,” Brookhart said.

There’s also something else Brookhart has noticed. The neighbors have been warm and welcoming to Gregory and his housemates. It wasn’t always that way.

“Sixty years ago, neighbors didn’t want anything to do with my brother,” Brookhart said. “It’s beyond wonderful.”

According to the state, 69 clients have been moved so far from PAT A at the Rainier School. Eighteen clients remain. The deadline to have them all out is September 30.

Gregory turns 67 next week. For the first time since he was 12, he will celebrate his birthday in his own home.

Related Stories:

‘The Situation Is Dangerous.’ Parents Sound Alarm Over Troubled In-Home Care Provider

Mysterious bruises. An unreported burn. Two vulnerable clients left alone overnight. These are just some of the complaints that families are leveling against Aacres WA — a troubled residential care provider that gets tens of millions of dollars a year from the state to care for people with developmental disabilities. Now state officials say they’re investigating.

Will The Passes Get Plowed? Impact Of Vaccine Mandate Firings On State Services Not Yet Clear

Roughly nine in 10 employees of the state of Washington are now vaccinated against COVID-19. Gov. Jay Inslee considers that a huge success and a win for public health. But his vaccine mandate has also led to the departure of hundreds of state employees. Now there are questions about the implications for some state services.

Washington Mother And Advocate For Developmental Disability Services: ‘Move To Oregon’

Currently, nearly 14,000 people who meet the Washington state’s criteria as developmentally disabled are not receiving services. They’re on what’s known as the no-paid services caseload.