All-Black Army Battalion Members Get Their Due 75 Years After Wartime Mission Over Northwest

Listen

It’s a story that seemingly has it all: a classified mission, dashing young men in uniform, leaps out of flying airplanes, stray bombs, plus some wildfires and a side of racial prejudice. The little-known slice of Pacific Northwest history featuring an all-black Army battalion is less likely to be overlooked now that the state of Oregon and people in Pendleton have put up a historical marker.

Eastern Washington University sociologist Bob Bartlett had a big hand in reviving regional interest in the veterans of Operation Firefly, which he only heard about five years ago.

“I see this picture of these paratroopers, these all-black paratroopers, boarding a plane. I said, ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa,'” Bartlett recalled in an interview. “It says 1945. I’m thinking, ‘I don’t know…’ I read the story. Immediately I was drawn in. Wait a minute. How did I not know this story?”

Bartlett has been hooked ever since on the history of the Triple Nickles. That’s the nickname of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion — the nation’s first black paratroopers. The U.S. military was segregated back then. Bartlett’s own father and uncle served in other segregated Army units in World War II , which seeded his interest in military history.

Bartlett said the Triple Nickles thought they were destined for Japan when they stopped at Pendleton Army Airfield in the spring of 1945. But no, they were about to be converted into smokejumpers for Operation Firefly. Professional smokejumping started in 1939 in Washington’s Methow Valley.

“They had two missions: to find Japanese balloon bombs and to dismantle or destroy them AND to fight forest fires,” Bartlett said. “At the time, the military thought those two things were connected.”

In the final years of WWII, Japan launched thousands of bomb-carrying hydrogen balloons to drift across the Pacific on the jet stream. Most probably fell harmlessly into the ocean, but hundreds reached North America.

“They dropped all over including Spokane and Boise, and Mexico and Alaska,” Bartlett explained. “As far away as Michigan and Iowa.”

The partial success of the enemy’s incendiary balloon barrage was kept hush-hush on the homefront to prevent panic.

Bartlett said he is motivated to make sure the soldiers’ story doesn’t get lost to the winds of time. That’s how his path crossed with the Oregon agency in charge of historical markers. The Oregon Travel Information Council wants to “fill in gaps” in whose history is recognized, says heritage manager Annie von Domitz.

Eastern Washington University senior lecturer Bob Bartlett, kneeling lower right, poses alongside other history buffs beside the new historical marker for the Triple Nickles in Pendleton on Aug. 30.

CREDIT: TOM BANSE / N3

It took several years of planning and fundraising before a diverse crowd could gather in the late summer heat for a dedication on Pendleton’s Main Street. Bartlett, who hails from Spokane, got the honor of cutting the ribbon for Oregon’s newest historical marker.

“Are the scissors sharp?” he asked as he hefted the oversized ceremonial shears. A sizeable audience of onlookers and history buffs let out a big cheer when three vigorous snips severed the red ribbon.

The interpretive panel succinctly describes Operation Firefly, the Triple Nickles and the Japanese balloon bomb barrage. The marker also is forthright in acknowledging the discrimination that 300 or so black soldiers experienced in Pendleton during that era.

Reached by phone in Florida, 96-year-old former Sgt. J.J. Corbett said the reception the elite troops got varied from friendly to racist.

“We met people who said they had never seen colored folks,” Corbett recalled.

Corbett distinctly remembers being taken aback by the signs on some business doors.

“During that time, we saw signs (that said), ‘No dogs and Indians are allowed,'” he said.

The African-American soldiers learned the prohibition applied to them, too.

“The reception was cold. We could not eat in any one of the restaurants,” retired Lt. Col. Bradley Biggs said in a 1990 oral history recording preserved at Howard University. “We found it difficult to buy a drink or a meal. Only two bars would serve us anything… Hotels in town would not serve us.”

The townspeople, he said, “were living in the Northwest but with a southern attitude.”

Once on the ground, the 555th parachute infantry wielded shovels and other standard firefighting equipment in cooperation with the U.S. Forest Service. CREDIT: NATIONAL ARCHIVES VIA EWU

Very few members of the Triple Nickles are still alive today, and none of them could make it to the late August dedication.

“I wished I could be out there,” Corbett said in an interview from his home in Bartow, Florida, ahead of the event. “I regret that I didn’t go back to Pendleton ever.”

Corbett said it took him a long while to realize his battalion had done things that were worth recognizing.

Pendletonian Brooke Armstrong, executive director of Pendleton Underground tours, contributed to placement of the historical marker. She said that while her city is different now, the discrimination that happened in the past “needs to be addressed.”

“I love how things are turning around,” Armstrong told public radio. “Maybe not everywhere in the world, but if we can make some impact on it, I’m all for it.”

Event organizer Kristin Dollarhide of Travel Pendleton said the marker dedication showed “it’s never too late” to make amends, even almost 75 years later.

The Triple Nickles — that spelling, by the way, derives from old English — weren’t stationed in the Pacific Northwest all that long. The battalion arrived in Pendleton in May 1945. They immediately received a crash course in smokejumping from Forest Service firefighters. Military assault parachuting and smokejumping use different procedures and gear.

The summer of 1945 was a dry one in the American West. Members of the Triple Nickles were called out to 36 wildfires spanning from Northern Washington state to Idaho to California, author Tanya Stone writes in her book “Courage Has No Color.”

Bartlett said it is difficult to judge if any of the wildfires the paratroopers fought were ignited by Japanese incendiary balloon bombs. The last of the balloon bombs launched from Japan would have crossed the ocean shortly before the Triple Nickles arrived in Pendleton, but the soldiers told historians they encountered and disarmed unexploded balloon bombs a few times in the Northwest woods.

A Japanese balloon bomb caused the only civilian WWII casualties in the contiguous U.S. During a Sunday school outing near rural Bly, Oregon, five children and a pastor’s wife died after they discovered a Japanese balloon lying on the ground and it exploded. This happened on May 5, 1945. At the time, the cause of death was censored to prevent the Japanese military from learning whether the balloon barrage was working.

The Triple Nickles were redeployed back to the Eastern Seaboard in October 1945. The trailblazing battalion would be folded into the 82nd Airborne Division a couple of years later, in an early example of racial integration of the U.S. military.

There is one other historical marker to remember the Triple Nickles in Oregon. It was erected in 2017 in the opposite corner of the state at the Siskiyou Smokejumper Base Museum in Cave Junction. That is close to the forested ridge where the first smokejumper to die while parachuting on a fire met his untimely end. PFC Malvin Brown was a member of the Triple Nickles who perished in August 1945.

Related Stories:

Federal funding cuts, freezes hit Palouse nonprofits

Palouse area nonprofits focused on helping with emergency food and the arts have had their funding frozen or cut.

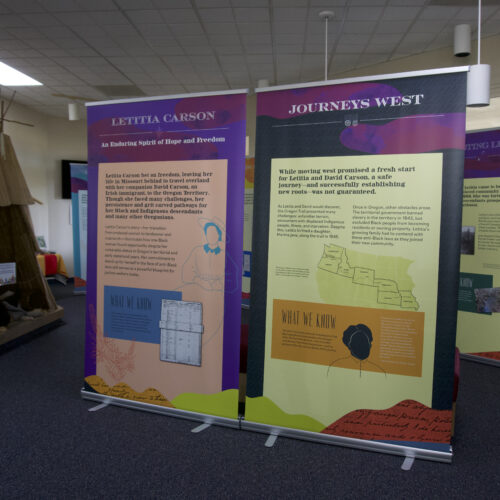

Whitman Mission hosts exhibit about Black female pioneer

A preview of the Letitia Carson exhibit at the Whitman Mission. (Credit: Susan Shain / NWPB) Listen (Runtime 1:09) Read Letitia Carson was a pioneer in more ways than one.

New Washington State University spring wheat variety named for Black family with deep roots in Washington

A field of WSU’s new variety, Bush wheat, growing near Lynden, Washington. (Credit: Washington State University) Listen (Runtime 1:05) Read Editor’s Note: Northwest Public Broadcasting acknowledges that all of what’s