A Confrontation With Music: Classical Pianist Ivo Pogorelich’s First Album In 21 Years

BY TOM HUIZENGA

Controversy has seemed to follow pianist Ivo Pogorelich at every move, even from the beginning. In 1980, when the 22-year-old whiz kid from Yugoslavia failed to reach the final round of the International Chopin Competition, the revered pianist Martha Argerich, who declared him a “genius,” stormed off the jury in protest. Naturally, the dustup helped launch his career. With a brooding pout, movie star looks and a high-powered record deal, Pogorelich was an instant celebrity. He told one journalist he could get a review just by cleaning the dust off his piano.

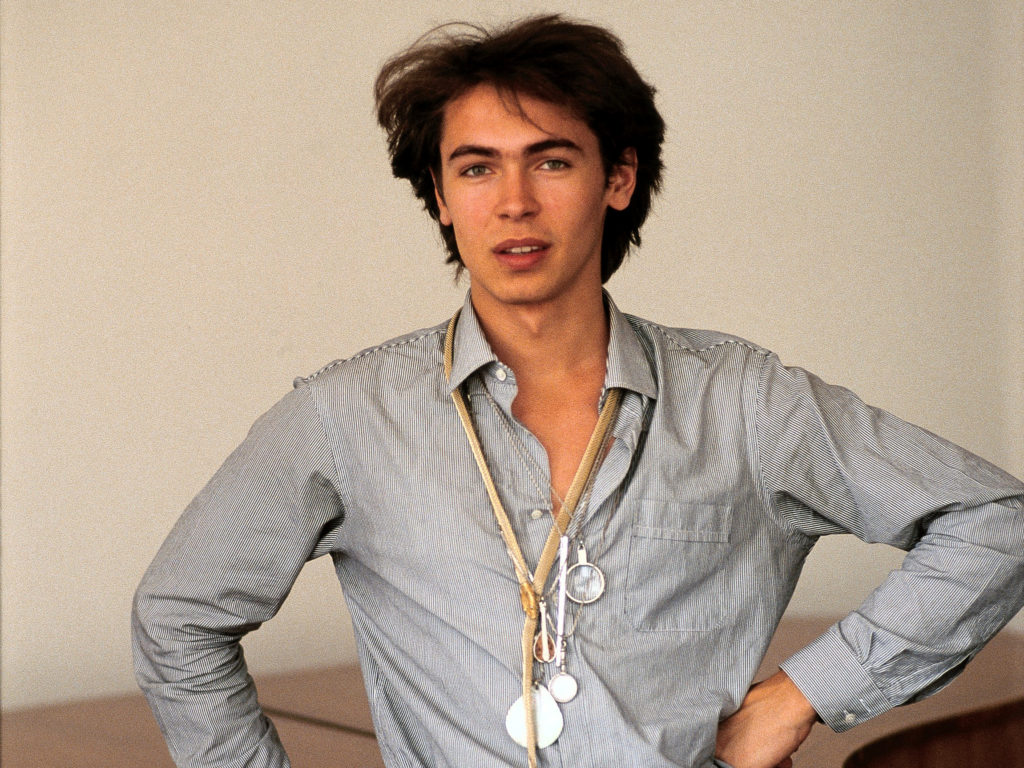

Ivo Pogorelich’s new recording of Beethoven and Rachmaninoff sonatas is the pianist’s first album in 21 years. CREDIT: Bernard Martinez/Sony Classical

But Pogorelich became polarizing. Blessed with a dazzling, seemingly effortless technique and a searching mind, the pianist routinely gave eccentric performances, pulling familiar music out of shape. In 2006, New York Times critic Anthony Tommasini closed a Pogorelich review by saying: “Here is an immense talent gone tragically astray. What went wrong?”

Now, at age 60, the mercurial artist is releasing his first album in 21 years, a recording of piano sonatas by Beethoven (Nos. 22 and 24) and Rachmaninoff (Sonata No. 2, revised version). With such a long hiatus — and Pogorelich’s track record — the release demands a certain critical wrestling to the ground, in terms of his once-lauded genius, and of broader questions, including where performers draw the line between artistic freedom and obligation to the composer. Instead of a traditional review, I’ve called in two experts – Anne Midgette, chief classical critic at The Washington Post, and pianist Patrick Rucker, a critic for Gramophone magazine — who sat around a table with me to explore ideas far beyond the perfunctory thumbs up or down judgement. We started by recognizing our own critical baggage, then listened to the music — compared his performances to other pianists — and by the end, arrived at two clear points of view, but left plenty of questions to ponder.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Tom Huizenga: What was your first thought when you heard a new Ivo Pogorelich album was coming?

Anne Midgette: The print reviews I had read of his performances in the last couple of years were so shockingly unanimous in their sort of — well, horror is the wrong word. Pity, in just saying, “He’s lost his technique; this is not professional.” I was thinking of him as a train wreck, and wondering about the motivation behind the album.

So I approached it with a kind of voyeuristic curiosity. And with that in mind, it was not the train wreck I thought it was going to be. It was not somebody who is incapable of getting through a single phrase of the music. There’s a lot to dig into. There’s also a lot not to like if you don’t want to like it. But it’s not incompetent in the way that it sounded like it might be, according to past reviews of his 2015 London recital.

Patrick Rucker: I was thinking about what I know of his biography, and the death of his wife in 1996. It seemed to me that she, also being his teacher, was an important element in his artistic personality. I think back on the career as a whole. I was hoping for a development, a flowering or something. Could he have come into his own and become more of his own person?

I was pretty excited to hear of a new album. In the early 1990s, I was a fan of his Brahms recording, even though he played some of the music twice as slowly as what you’d consider a normal tempo, such that the architecture nearly collapsed. Going back to that album now, I can’t say I’m as much of a fan as I was.

What about Pogorelich’s choice of repertoire for this album? We’ve got a pair of arguably undervalued — maybe even unloved — Beethoven sonatas, Op. 54 and 78, along with the Rachmaninoff Second Piano Sonata in its revised version.

Midgette: It did seem to me he picked pieces that already had in them a certain tendency to wildness. Some of the stuff he does in music fits very well with the tender and explosive elements of these pieces. They’re a good place to have a tantrum, if you will.

Right. In the opening measures of opus 54, Beethoven unfolds this beautiful Haydn-esque melody and then a sudden turn towards violence, with pounding double octaves and punchy accents. Patrick, these are Beethoven sonatas you’ve played yourself.

Rucker: It’s true. Two less familiar Beethoven sonatas, certainly. The opus 78 is a gem, a masterpiece, particularly. But Beethoven and Rachmaninoff is an unusual coupling. I think you could see, say, Chopin and Rachmaninoff, or Rachmaninoff and any of his compatriots perhaps. But it’s an unusual thing. Maybe it’s to show the variety he’s capable of.

Now let’s hear some of your overall thoughts after listening to the album closely.

Midgette: Once I was past the thing of, “OK, it’s not the train wreck that those reviews led me to believe,” I can’t say that I was enraptured. But I thought, “It’s legitimate.” One of the painful things about hearing some of these interpretations in general is that the urge to put your own stamp on music that’s been played 5,000 times almost necessarily leads you to be eccentric and excessive, because everything’s been done. His feelings are all over this: It’s very loud and then it’s very poetic. He can do really, really slow, too. But I found a poignancy in the reading beyond my impulse to say, “That’s not how it goes. That’s not right.”

The other sad thing is that, almost always, these individual, quirky readings lack all lightness or humor. There’s this furrowed-brow insistence on getting your personality out there, and that’s not what the music is really about.

We often find these eccentricities in younger players who are just emerging, just coming into their own, trying to stand out from the crowd. And we chalk it up to youth and figure they will mature. But listening to Pogorelich’s album, I thought that the willful, very eccentric way he deals with tempos and dynamics has really been his path from the beginning.

The young phenom: Ivo Pogorelich, early in his career, when he was regularly recording albums. He’s just released his first album since 1998.

Susesch Bayat/Deutsche Grammophon

Rucker: I find the approach to these performances so eccentric. If you want to have a really original focus on a piece of music, to make it completely your own, there’s a process that goes into that — which is, you have to try like crazy to push everybody else’s ideas out of your mind, and then look at the notes and so forth. But there are so many instances, particularly in the Beethoven Sonatas, where the rhythms are even misread. It’s just so much a personal take, an eccentric take, on what’s on the page.

Quite apart from the interpretation, I found the piano playing to be very brutal — ugly sounds which I don’t think are necessarily a part of Rachmaninoff. And that’s the piece I was most focused on because I thought it had the greatest potential for personal expression for him. Also, I noticed that the life of the phrase — you can pull it just so far. It couldn’t possibly be sung.

It’s almost as if every short passage and/or phrase is under a microscope and has no relation to the phrase or passage before or after it.

Midgette: Which is, again, an ill of our time. Conductor Christoph Eschenbach does that. You’re so focused on making the music of this phrase that you end up with a pile of ashes — of just phrases piled on top of each other.

Rucker: And I’d like to return to something you said, Anne: Not only is there no humor to it, there’s no relief to it. It’s relentless in its — I can’t say urgency because it doesn’t really sound urgent to me, but relentless in its intent.

Midgette: I felt Pogorelich’s attempt to rip the skin off these things and sort of remind you of what it would sound like new, when Beethoven was first playing: the assault on the ears that it represented to people and the shock of that back then. I did think of deaf Beethoven pounding at the piano, and how people learning the music internalize the idea that Beethoven is clawing at the piano to make music. I think Pogorelich is getting at something in the pieces that is there. He wasn’t totally off the rails in the way he approached it.

In the final movement of the Rachmaninoff Sonata, especially, there are passages that rely on meticulously building tension, but in Pogorelich’s hands that tension seems to vanish.

Midgette: He’s building the tension in a different way. I don’t think he feels the tension any less — he’s kind of digging inside it. And it seems to me he’s sort of pursuing his own thoughts about it rather than worrying about the effect it’s going to make on the audience. The point of what he’s doing is exploring himself, and anybody who wants to come along with him will come with him. But maybe the biggest drawback of the interpretation is the degree to which it’s deliberately willful.

But are these willful interpretations valid?

Midgette: If you get up and play, it’s valid. Pianist Tzimon Barto said this great thing to me once: “If I go up on the steps of the Acropolis and slit my wrists and yell and scream and pour red paint around, the Acropolis is fine; they can mop up the paint and it’s not going to hurt the Acropolis. It’s just me up there making a fool of myself.” So that piece is not damaged by what Pogorelich does it to it. People may not want to listen to it; is that invalid because people don’t like it?

Pogorelich is not certainly not the first eccentric. Look at all the opera singers from the pre-World War I era who put their very individual stamp on interpretations and did whatever they wished with tempos and added extra notes. Even closer to today, there are people like Glenn Gould. Personally, I can’t bear hearing the first recording of the Goldberg Variations; it sounds like a sewing machine playing Bach. And then you’ve got wonderfully eccentric conductors like Teodor Currentzis and violinists like Patricia Kopatchinskaja.

Rucker: But Kopatchinskaja is communicating. There’s no question that she is trying to say something to the audience. With Pogorelich, I don’t get that. I feel like he’s got this jigsaw puzzle in front of him and he’s picking up each piece and staring at it. It doesn’t sound to me like finished work.

Midgette: I feel like I’m hearing him find things. It doesn’t all come together in something neat; I don’t think he wants it to. He doesn’t want to give you a big, finished, nicely put together jigsaw puzzle. Whether that’s something everybody wants to listen to is another thing.

Now, does it represent the composer’s intentions? We have so many directives about how we’re supposed to play music. Look at the historically informed performance movement: One reason people are drawn to it is that there’s more freedom — freedom to improvise and move within a wider spectrum and still be within the rules of how it’s played. With the 19th-century repertoire, the rules are very codified.

And then there’s the idea that you’re not supposed to color outside the lines. In classical music we have these pieces written down and accepted as masterworks. Musicians are taught to play them within these strictures, and if you venture outside of them there’s going to be a problem. Of course, there’s nothing like that in jazz, where there’s so much more reliance upon improvisation and individuality.

In the slow movement of Pogorelich’s Rachmaninoff, at one point I feel like we’ve just walked into a piano bar because the tempo is so relaxed. It takes on a kind of improvisatory feel, like, “Where is he going to go next?” But I don’t exactly hate it.

Rucker: Maybe it’s worth pointing out that we’re so far removed from Beethoven, but with Rachmaninoff, we know what he sounded like. We have recordings — not of this particular sonata — but we have an idea of what his ethos was as a performer and as a composer.

I remember a teacher of mine once said, “The beauty of Bach is that you can play it at any tempo.” Well, no, you can’t. It’s a dance, or it’s an aria, or it’s one of these things that are recognizable from the depth of your understanding of the style. So does that matter? Are we redefining it for ourselves for a new age, which of course every age must? What’s our obligation to the original?

Midgette: You say we know what Rachmaninoff sounded like. But in jazz, if you know what Louis Armstrong sounds like and you want to play a Louis Armstrong song, the whole point is you take it over and make it your own rather than slavishly emulate. In classical music, the emphasis is all on slavishly emulating. And then we get very cookie-cutter performances and we wonder why audiences aren’t coming.

And that’s what a lot of people complain about today: There’s a certain sameness to not only, say, violinists, but to orchestras as well. We’re looking for individuality. So the question is, where are those lines between individuality, eccentricity and artistic failure? Patrick, I sense this album may be closer to an artistic failure in your mind.

Rucker: You know, in a way it is. If we want to use this music as a springboard, why don’t you call it a “Fantasy on the Second Sonata of Rachmaninoff?” I ask this sincerely, not sarcastically. I think there’s a question of authorship and a question of curatorial responsibility. I also believe that you can hew the line down to the tiniest detail of what we have in the score and still have a vibrant and vital interpretation that will have people standing on their seats.

Midgette: Oh, there’s no question that’s possible. But the question is, when presented with something different, does one rule it out on the grounds of not playing by the rules? Last spring, I heard a mashup of the Verdi Requiem with Shakespeare’s King Lear, with Lear played by a woman and the Requiem performed by eight voices. It was very honorable and fascinating. Now, it wasn’t Lear because it was a one-woman monodrama; it wasn’t by any of his rules and it wasn’t the play. But I think in theater we have no problem understanding that it was Shakespeare. So to say it’s inauthentic because Pogorelich is taking tempos slower — this is the kind of thing that makes people who are outside the classical field say, “Oh for God’s sake!” If somebody new comes to it, whether or not they like it, it is a thing. It’s a reading of Rachmaninoff, an eccentric reading of Rachmaninoff.

What value does the album have if it is presented to someone who has never before heard any of this music?

Midgette: I was wondering that as I was listening. It’s quite close to home, too, because I have a 7-year-old and he likes contemporary music. He doesn’t like my stuff at all and makes snap judgments about things.

One of the things people respond to — and people think is part of classical music, which drives me kind of crazy — is the “itness” of it all. And by that I mean the idea that classical music expresses only grand thoughts and grand feelings and needs performances writ large in capital letters. In a sense, Pogorelich’s interpretations push that to a certain height. But I think that’s something that new audiences who don’t know much about classical music are also primed to want. And they’re certainly going to find it in this recording.

Rucker: As far as the vitality of the expression we talked about in violinist Patricia Kopachinskaja: I’m there, I’m buying it. I don’t care if she plays barefoot. Somehow she has internalized the message in a broad range of repertoire. She’s internalized it that so it can just come out and speak. Pogorelich doesn’t sound that way to me. It doesn’t sound to me like he’s internalized it. It sounds like he’s not owned it, and he doesn’t really love it.

It’s hard to know what it means for an artist to chase an idea and document it in an album. We can’t get inside Pogorelich’s head, but you’d think he must have had some broad idea about what he wanted to say with these pieces — even if it was just, “I need to play them my way, and play them very differently.”

Midgette: Patrick, what you said — it was such a beautiful way you put it — about you don’t hear that he really loves it, that resonates with me. I think of hearing Evgeny Kissin play, and the way Kissin’s mind works as an artist. He is dazzling and amazing; I don’t always get that he loves what he plays. But as a criterion, while there is no question that Kopachinskaja has it, and that that’s a wonderful thing, it does manifest differently for different people, especially for somebody who’s been through this whole prodigy thing.

I want to read a recent quote that’s right in line with what we’ve been talking about. In the Swiss paper Neue Zürcher Zeitung, the pianist Igor Levit was asked: “So, you are opposed to the widespread ideal according to which the interpreter is primarily the servant of the musical text?” And Levit answers: “I do not feel like a servant, not even a master of anyone. For me the question is not what would we be without the composers, but what would the composers be without us? The interpretation is my personal response to the information provided to me by the score.”

Midgette: That’s a really healthy way to look at it, because this state of servitude to the composer’s wishes is fine if you really feel it, but it’s become a template for the classical field — a field that needs more creativity and is really hungry for it.

Rucker: I think your diagnosis of the field is 100% right. We really need some fresh thought. I also have a quote I wanted to read, from the New Yorker critic Hilton Als, who recently wrote: “What you look for is just how committed players are to connecting with the audience through their craft, the skills that allow them to exhibit and illuminate the awfulness and the lushness of what it means to be a person in the world.”

And I guess that’s what I’m looking for. I’m not looking for the “correctness” of it. But I would like also to feel that if musicians are saying, “Here’s Beethoven,” “Here’s Chopin,” that somehow those characters are recognizable and not just a suit of clothing the musician puts on for their own pleasure. I want their motivation to be my pleasure.

Midgette: Although I did feel in this album that you’re hearing somebody who’s been through a lot, as far as “the awfulness” of being in the world.

You can hear the struggle?

Midgette: That’s part of the “itness” of it all that I roll my eyes at. But yes, I think you can hear a kind of confrontation with the music. He’s not taking any easy answers and he’s not accepting it at face value. I thought a lot about why I respond to this more warmly than a concert I heard last year by Fazil Say, who had some of the same characteristics in terms of sort of assaulting and redoing, and I find Pogorelich a lot more simpatico. Because Say was just loud, and Pogorelich does have poetry, even if he’s stretching it like taffy.

Where does this all leave Pogorelich? It’s been 21 years since his last album. Is there some of that “genius” — as Martha Argerich said of him in 1980 — left in his playing? Maybe flawed genius?

Rucker: I would love to hear more curiosity. I would love a deeper look in his music-making than I think he is willing to give us at this point, at age 60.

Midgette: Genius is a word that gets so thrown around in this field. Is he a serious piano player? Yes. Is he going to scale the heights and become a world phenom the way he was and be booked by every orchestra? No.

As a critic we’re supposed to come up with thumbs up or thumbs down. I think the fact that we’re sitting around the table discussing the album means that if you care about piano playing and you know anything about Pogorelich, you’ll probably want to hear it. Is it a huge success, is it something you want to listen to again and again? I’m not sure. And I’m not sure where it leads him. I would hope he’d make a couple more albums before we write him off or hail his return based on this.

Rucker: Well, Anne is the wave of the future and I’m the old fuddy-duddy! [Everyone laughs]

Midgette: But it’s actually really good to have the two perspectives. I think we had two clear points of view, and people will agree with one or the other.

Ivo Pogorelich’s new album of sonatas by Beethoven and Rachmaninoff is out Aug. 23 on Sony Classical.