Washington Reduces Number Of Foster Youth Out Of State, But In-State Beds Still Lacking

LISTEN

A year ago, Washington state had 82 hard-to-place foster youths, mostly teenagers, living in facilities in states as far away as South Carolina, prompting calls to bring them home.

As of Aug. 1, that number had been reduced by more than half to 38, according to the Department of Children Youth and Families.

“I’d say that’s pretty significant progress,” Ross Hunter, the department’s secretary, said in an interview Tuesday.

Last year, Hunter set a goal of bringing all out-of-state youth back to Washington within 18 months.

But meeting that April 2020 deadline may prove difficult because of the complexity of the needs of the remaining youth and a persistent lack of available in-state beds.

“It’s a slow burn,” Hunter said.

DCYF took over the state’s foster care system from the Department of Social and Health Services on July 1 last year. Washington typically has about 9,000 youths in foster care; out-of-state youth have accounted for approximately 1 percent of them.

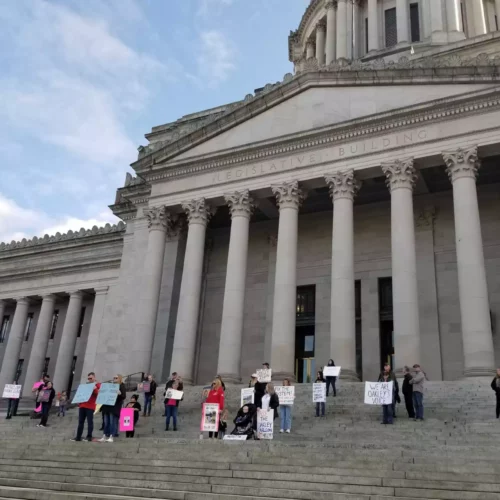

The push to bring the foster youth back to Washington gained urgency in October 2018, when Disability Rights Washington (DRW) issued a scathing report titled “Let Us Come Home.” The report focused on conditions at Clarinda Academy in Clarinda, Iowa, and concluded that Washington youth placed there “suffered additional emotional and psychological harm.”

In response, DCYF announced it was halting new placements at Clarinda Academy and would work to move the youth at the facility into permanent settings. No Washington youth remain at the facility, according to DCYF.

This spring, DCYF also removed youth from Red Rock Canyon School in St. George, Utah, following a large fight at the facility in April and reports of staff-on-youth assaults. In July, the school announced it would close its doors.

Both Red Rock and Clarinda Academy are operated by Alabama-based Sequel Youth and Family Services, a for-profit company whose majority owner is Altamont Capital Partners, a Silicon Valley-based private equity firm.

The State of Oregon also placed youth at Red Rock Canyon School and Clarinda Academy. In recent months, Oregon lawmakers have put pressure on state child welfare officials to bring foster youth back home.

As of this week, Oregon had 44 youths in 13 different out-of-state facilities, according to the Oregon Department of Human Services. That’s down from 84 in February. Three youths remain at Red Rock Canyon School as it prepares to shut down.

Foster youth who are sent out of state generally have a history of trauma and require therapeutic care that exceeds what a traditional foster home can provide.

In Washington, the state lacks an adequate number of therapeutic beds to care for the youth in-state. In fact, the number of group home beds has declined over the years after provider rates were frozen during the Great Recession. In addition, turnover among direct-care staff in group homes hovers near 60 percent, according to a study commissioned by DCYF.

In response to the crisis, the Legislature this year approved a nearly 45 percent increase in the reimbursement rate for providers of Behavioral Rehabilitation Services (BRS). The new, higher rates, which kick in Oct. 1, are designed to allow group homes to operate at 80 percent capacity while still breaking even.

But even as the rates are set to increase, the bar is being raised for congregate care facilities. Under the federal Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA), states that want to leverage federal foster care dollars must ensure group homes are accredited and provide a higher level of therapeutic care.

In addition, these facilities also must meet performance metrics as part of their contracts, such as reducing average stays by 10 percent and providing six months of aftercare support.

According to DCYF, the higher BRS rates will allow group home operators to keep up with Washington’s rising minimum wage. But the agency says the rates may not be sufficient to cover the cost of all of the new federal requirements.

Under the new rate structure, group homes that meet the federal requirements will be paid approximately $12,800 per month, per youth.

Even as the state works to bring back youth and shore up the BRS system, another challenge persists: the number of foster youths who spend the night in hotel rooms or in DCYF offices because there is nowhere else to place them.

As of Aug. 1, DCYF had recorded 1,035 foster youth hotel stays, up from 824 in all of 2017.

“It’s dangerous for staff and it’s not therapeutic,” Hunter said.

Washington currently has approximately 300 group home beds. Hunter said ideally he’d like to have 200 more, but said it may take six months to a year to start bringing new beds online.

Only about 5 percent of Washington foster youth are in group homes, or what is known as congregate care. The national average is 10 percent.

Lauren Dake of Oregon Public Broadcasting contributed to this story.

Related Stories:

Rape, beatings and racial slurs: None of it was enough to shut down this Idaho youth facility

Employees at Cornerstone Cottage alerted state officials to the dangers, only to be fired themselves Cornerstone Cottage opened in 2016 in Post Falls, Idaho, a booming bedroom community 25 miles

WA bill meant to safeguard foster children appears to have died in committee

A bill inspired by the case of missing child Oakley Carlson is stalled in the Washington Legislature. But supporters hope it can still be revived.

Foster Families Needed – May Is Foster Care Awareness Month

Foster Families Needed – May Is Foster Care Awareness Month