The U.S. Once Had A Ban On Assault Weapons — Why Did It Expire?

BY RON ELVING

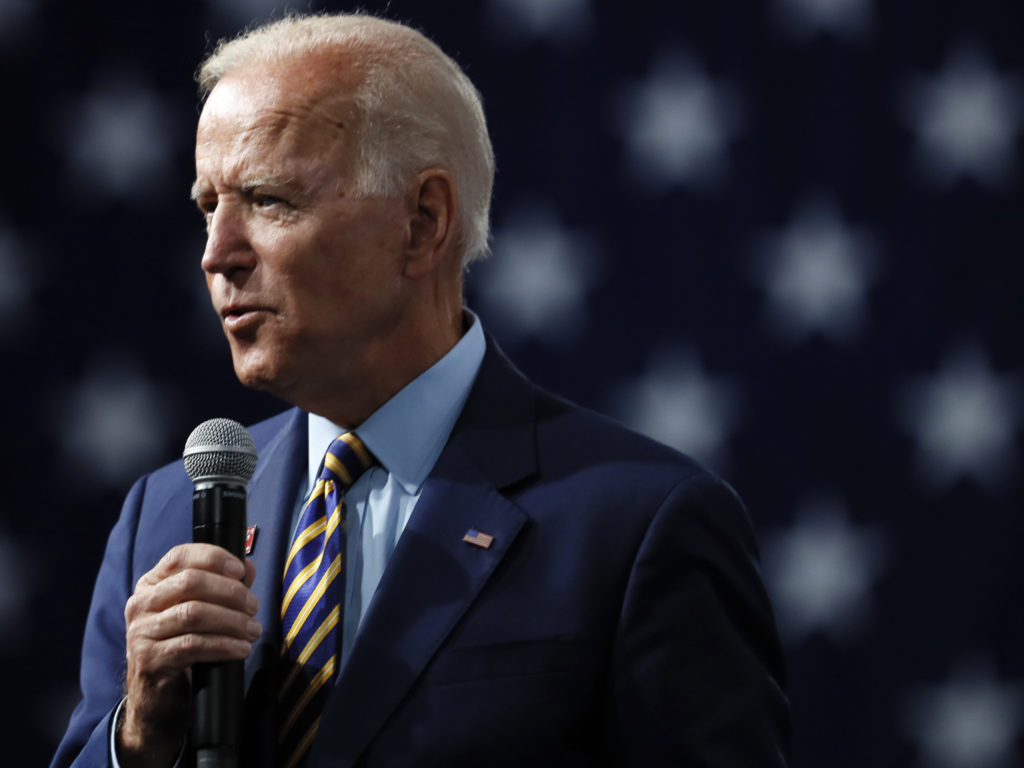

On the presidential campaign trail in Iowa and on the op-ed page of The New York Times, former Vice President Joe Biden has made the case for going back to a nationwide ban on assault weapons and making it “even stronger.”

Some have reacted with quizzical expressions: “Back?” “Stronger?”

Yes. Twenty five years ago, when Biden was chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Congress passed the Public Safety and Recreational Firearms Use Protection Act — commonly called the assault weapons ban.

It prohibited the manufacture or sale for civilian use of certain semi-automatic weapons that could be converted to fire automatically. The act also banned magazines that could accommodate 10 rounds or more.

A visitor peruses H&K rifles at the SHOT Show in Las Vegas. Such weapons were once restricted under a 1994 ban that expired with changing politics in the United States. CREDIT: John Locher/AP

“Assault weapons — military-style firearms designed to fire rapidly — are a threat to our national security, and we should treat them as such,” Biden wrote in his weekend op-ed. “Anyone who pretends there’s nothing we can do is lying — and holding that view should be disqualifying for anyone seeking to lead our country.”

The earlier ban was enacted as a subsection of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, an election-year package meant to show that Democrats were “tough on crime.”

Times were different then. More Americans said they worried about violent crime and the threat associated with criminals armed with powerful weapons.

So among other things, Biden and Democrats got behind stricter sentencing guidelines and expanding the category of federal crimes punishable with the death penalty.

At the time, Biden defended the legislation against charges of weakness by saying: “We do everything but hang people for jaywalking in this bill.”

Eagerness to tackle crime rates made at least some Democrats in 1994 also willing to address the role of guns – particularly those perceived as more dangerous and which had been turned on innocent citizens.

In his Times op-ed, Biden salutes the senator often credited as the architect of the 1994 ban, Dianne Feinstein of California. Then, in just her second year as a senator, Feinstein took over as chief sponsor of a bill originally offered by Ohio Democrat Howard Metzenbaum in 1989 after a mass shooting on a schoolyard in Stockton, Calif.

That shooting took the lives of five children and injured 28 others and a teacher.

Feinstein’s resolve to carry this legislation forward was bolstered when eight more people were killed and six injured in another California horror, this time at a law firm in San Francisco.

“It was the 1993 mass shooting at 101 California Street,” she later said. “That was the tipping point for me. That’s what really motivated me to push for a ban on assault weapons.”

But to secure the votes for passage, the ban’s sponsors agreed to allow those who already had these guns to keep them. Biden now says he would initiate a buyback program instead, although it isn’t clear how that might work or how effective it might be.

Sponsors also accepted a “sunset provision” by which the 1994 ban would automatically expire after 10 years unless renewed by a vote of Congress. Even so, the ban only got 52 votes in the Senate on its way to inclusion in the overall crime bill, which was signed into law by President Bill Clinton.

The world turns

By the time those 10 years had passed, however, the political climate had changed.

Republicans by then had held the House throughout the period and the Senate for all but 18 months. The GOP had just increased its numbers in both chambers in the midterm elections of 2002, a political season dominated by anxiety after the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

On top of all that, the president in 2004 was George W. Bush, another Republican who was opposed to renewing the ban.

Feinstein and others made numerous efforts to restore the ban that year and over the next several years. When Barack Obama was elected president in 2008 he made renewing the ban part of his agenda. Efforts were mounted again after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in December 2012, but none bore fruit.

Former Vice President Joe Biden says if he’s elected, he’d support a new ban on assault weapons, along with a buyback program.

CREDIT: Charlie Neibergall/AP

The attempt to reinstate the ban after Sandy Hook attracted 12 fewer votes in the Senate than Feinstein had mustered in an attempt to renew the ban in 2004.

Legacy

Biden has come to rue much about the 1994 legislation.

It led to a surge in prison populations that has since been reviled as “mass incarceration” that proved disproportionately injurious to African Americans. Biden has been upbraided for it by his rivals since this year’s Democratic presidential contest began.

But in 1994, the most immediate consequence of the crime bill was a backlash against the assault weapons ban among gun advocates.

The midterm elections that fall were already difficult for the Democrats, who had to defend the new North American Free Trade Agreement, some higher taxes and a scandal in the House banking system.

Adding in the blowback over the assault weapons ban — particularly intense in the rural South and West — turned the midterm into a debacle for Democrats. They lost control of both the Senate and House, the latter for the first time in 40 years.

Among those defeated that fall was 42-year veteran Jack Brooks, a Texas Democrat who had been chairman of the House Judiciary Committee when the crime bill passed.

Brooks had tried to have the assault weapons ban removed from the bill and was himself a longtime member of the National Rifle Association. But it was not enough to save him in rural Texas that fall.

The sense that gun control cost Democrats votes intensified after the presidential election of 2000. That year’s Democratic nominee, Vice President Al Gore of Tennessee, could not carry his home state or other swing states won by the Clinton-Gore ticket in the 1990s.

Gore surely paid a price for his stances on coal and other issues as well, but much of the blame for his narrow Electoral College loss fell on voters’ response to his positions on guns.

In 2004, when the Republican Congress refused to renew the assault weapons ban, the Democrats’ presidential nominee was Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry, who sought to style himself as a hunter and gun owner but nonetheless supported the ban and its renewal.

The Electoral College that year looked a lot like 2000, and Kerry could have won had he carried Ohio. But in that state, as elsewhere, a poor showing in rural counties doomed the Democratic nominee.

What effect did the ban have?

Today we can look back at the 10 years of the ban and at 15 years since its expiration.

Critics of the ban have argued that it violated Second Amendment rights while accomplishing little, and evidence suggests it did not do much to reduce the incidence of gun violence overall.

What it did, its defenders reply, was reduce the number of people killed in mass shootings.

Both sides of the debate claim vindication in subsequent research. Comparing the various studies is difficult because they use different definitions of “assault weapon” and mass shooting.

One thing is clear: Assault weapons like those once restricted by the ban were used in the most memorable events that have defined the current era of random massacre, including at Sandy Hook in 2012, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., in 2018 — and this month in Texas and Ohio.

They are the emblem of the nation’s soul sickness over these tragedies.

So today Democratic candidates stand by the assault weapons ban, despite its political costs in the past and potential costs in the future.

President Trump now calls for having “strong background checks” for gun purchases but does not call for new restrictions on assault weapons.

“There’s no political appetite for it,” he says.

But many surveys show the opposite.

A survey done this month by Morning Consult and Politico found 7 in 10 voters, including 54% of Republicans, supported “a ban on assault-style weapons.” Even higher percentages supported a ban on high-capacity magazines and a purchase age of at least 21 for any gun. The survey, done Aug. 5-7, included 1,960 interviews and had a margin of error of two percentage points.

Given that similar percents supported a ban after the shootings of the early 1990s and after the Sandy Hook and Parkland tragedies, there would seem to be a long-term pattern.

Whether that can be translated into legislative action by the current political establishment is — as always — another question.