BOOK REVIEW: ‘When I Was White’ Centers On The Formation Of Race, Identity And Self

BY HOPE WABUKE

When one thinks of American blackness, there is the unsaid ugly truth that nearly all American blacks who have descended from the historical African diaspora in America have one (or several) rapacious white slave owners in their family tree at some point.

Here, in the early days of the United States, was the invention of racism for economic necessity. From 1619 until 1865, white male Americans chose to breed a black enslaved workforce through the state-sanctioned rape of black women to build the new nation and support their white supremacist class. Race became the single unifying identifier — determining everything about one’s life starting with this most basic division: enslaved or free.

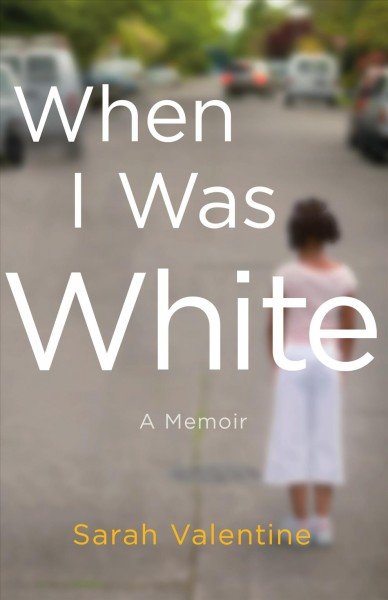

When I Was White: A Memoir, by Sarah Valentine, right.

The American law was that the “condition of the child followed that of the mother,” backed up by the “one drop rule,” the legal framework that dictated even one drop of blackness made an individual black, never white. The idea of blackness as a pollutant, a taint that would erode the purity of whiteness, was seized by politicians around the world then — and now.

Because of this legacy of sexual violence and anti-blackness, black and white mixed individuals have long been considered black in America.

To a much larger degree than many people would like to admit, race still determines a vast part of one’s life — social networks and mobility, birth and other medical care, employment opportunities and so on. Indeed, there is an entire genre of literature and film, popularized in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, composed of blacks “passing” for white to avoid this racism. Some of the most famous examples are Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel, Passing; James Weldon Johnson’s 1912 opus, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man; and the 1959 film The Imitation of Life.

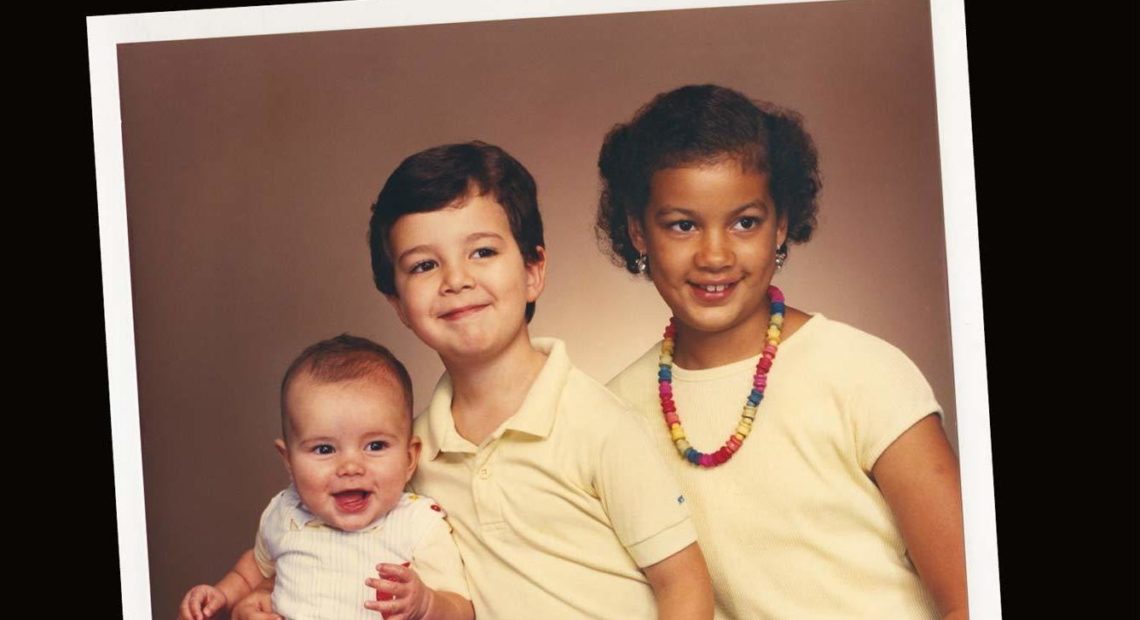

Sarah Valentine, the author of the memoir When I Was White, did not choose to pass for white; her mother made the choice for her. So Valentine was raised as white by white parents in white middle-class communities — only to discover as a young woman that her biological father was actually black. As Valentine endeavors to explore what her new identity means to her, she searches for ways to connect to her blackness. For Valentine, learning that she is black is to reject whiteness; she cannot comprehend how the privileges of whiteness can be held hand in hand with the racism the black body is subject to.

When I Was White

A Memoir by Sarah Valentine

Valentine has good reason to feel this way; her space of “passing” for white puts her in situations where, because they assume she is one of their own, she hears the racist things white people say when there are no black people around — starting with her own family. Valentine’s pain when her mother refuses to let her attend a school dance because her date is black, dismisses black people as lazy welfare spongers who live in the ghetto or bans Valentine from watching TV shows with black people is palpable.

Because of her white mother’s ongoing racism throughout her childhood, Valentine’s first understanding of blackness is as other — as negative, dangerous and wrong. “I got the message that black was undesirable,” Valentine writes.

At the center of When I Was White is this immensely complicated relationship between Valentine and her mother. As Valentine seeks to learn more about her biological father, her mother will only say: “Your father was a black man who raped me in college.” Valentine tries to reckon with this, seeking more information from her mother — and in the aftermath of her mother’s ever changing narrative of Valentine’s conception and constant refusals to answer Valentine’s questions, she seeks answers from her mother’s college friends as well. Valentine, torn between respecting her mother’s trauma and wanting to connect with her biological father, struggles to come to terms with the many layers of the situation, navigating the line between the importance of believing women’s accounts of rape and the awareness of the history of white women’s false rape accusations against black men as an excuse for lynching and other racial violence throughout American history.

Valentine is at her best when we see her sift through this history, creating well-crafted scenes that resonate with depth and emotional weight in a commitment to get to the truth — even if it paints her in a negative light. She reveals that everyone suspected she had black heritage — friends, teachers, even she herself — but to prevent jeopardizing her family dynamic, no one spoke of it. Scared, the young Valentine had also remained silent.

“I worried that acknowledging I was black and had a different father than the one I grew up with could shatter the unity of the family my parents had worked so hard to create,” Valentine writes. Indeed, after taking a DNA test and finding out they are not biologically related, the man Valentine knew as her father moved out of the home he shared with Valentine’s mother and into an apartment of his own 300 miles away.

Black and white biraciality in this country has long been understood as a type of blackness, and the presence of biracial individuals within blackness has added to the power of the black cultural block. Without biracial being considered black, for example, America would not yet have had its first black president.

But why, then, is biracial not also a type of white? If you look past the racist origins of the “one drop rule,” what happens to our thinking of racial duality?

One wonders: Why is this mutually exclusive? Why must Valentine choose either black or white? One wonders, too: If the author was Latina and black or Asian and black, would discovering her blackness mean losing her Latinx or Asian identity? We are beyond black and white, beyond the “one drop rule,” in American society. So, should our understanding of multiracial identity evolve too? Can it evolve?

Or is the history and continued presence of white supremacy in our culture so virulent that whiteness cannot be held in the same conversation as other multiracial identities?

These and other questions are tackled in When I Was White. But in a larger sense, Valentine’s memoir documents an experience any black individual in the U.S. has had: From birth you have seen yourself as a normal human being, worthy of just as much respect and personhood as anyone in America. But then, upon that first pivotal experience with racism, you realize that in this society, because of your skin, you are seen as other; because of your skin you are seen as less than and treated accordingly — and always with the threat of violence against your body ready to rise.

As the United States continues to become more brown and black and less white — resulting in a xenophobic backlash against brown and black Americans and a nostalgia by some for white European immigrants — the ideas in When I Was White become even more necessary. Here, quite simply, is a masterful explication on the formation of self and identity — of learning to trust yourself instead of the lies other people, no matter how close, tell you about who you are.

Hope Wabuke is a Ugandan-American poet, essayist and writer. She is a contributing editor for The Root and has written for The Guardian, The Sun, Creative Nonfiction Magazine, The Daily Beast and Salon, among others.