Creedence Clearwater Revival’s ‘Green River’ At 50: An Essential Guide To Early CCR

PHOTO: The original lineup of Creedence Clearwater Revival, at London’s Heathrow Airport. L-R: Tom Fogerty, Stu Cook, Doug Clifford, John Fogerty. CREDIT: Michael Putland/Getty Images

BY TOM MOON

The official history of rock and roll in the late 1960s is usually written festival-to-festival, Fillmore lineup to Fillmore lineup. Here are the reputation-making gigs, here are the moments when youngsters became rising stars.

But there’s an alternate history, and it involves those same bands as they were presented to America on television variety shows. By 1968, rock was well established as a cultural force; even hosts antagonistic to the music were regularly showcasing it. The best-known and most coveted platform was The Ed Sullivan Show, which, after introducing The Beatles to the U.S. in 1964, became an essential stop on the promotional train to mainstream success. But there were other, less-watched shows also booking bands — the Carson Dalys of their day — which were regarded by artists and managers as necessary stepping stones.

Which explains how Creedence Clearwater Revival wound up on crooner Andy Williams’ NBC show in the summer of 1969.

The performance, taped shortly before Woodstock, opens with a troupe of smiling young people in marching band uniforms, holding tambourines and trumpets while cheerfully high-stepping around the small set, singing. The refrain: “In this world of troubled times, we all want survival / One solution seems to be… Creedence Clearwater Revival.”

A fog rolls in — and there’s John Fogerty, in a fringed brown-suede vest, clawing the opening guitar line to “Green River.”

Fogerty and the band lean into the tune, doing their best to evoke the idyllic mysteries of a place where bullfrogs call and kids play on rope swings. But the quartet is, oddly, still surrounded by the marching troupe – human props, frozen in place and lit in silhouette, trumpets aimed skyward. The only time Fogerty shows emotion is around 1:50, when there’s an unwanted surge of feedback, prompting a live reverb rejiggering. He shakes his head, smiles in that “whatever” way and then gamely plunges back into the song.

It’s not surprising that TV producers didn’t get Creedence Clearwater Revival. During its rapid ascent in 1969, even those inside rock culture didn’t really know what to make of the band. Here was a group from San Francisco that was pointedly not interested in, or aligned with, the city’s most intriguing (and best-known) export, psychedelic rock. A band that was not into drugs, that positioned itself as counter to the counterculture. A band that mythologized the American South with an exotic mixture of blues, New Orleans R&B and rockabilly, despite being a product of California. A band that had a sound built for FM radio, but songs that adhered to the tight verse/chorus requirements of AM.

The commercial rise of Creedence seems torrid, almost paranormal, in hindsight — by the end of 1969, Creedence had three top-10 albums on the Billboard 200, and four top-five singles on the Billboard Hot 100. But that pales in comparison to its artistic evolution: During an incredibly prolific 18-month stretch — approximately from the recording of Bayou Country around October 1968 to the recording of Cosmo’s Factory around May 1970 — the band developed a distinct and instantly recognizable sonic signature. It applied that soundprint to direct, tuneful, incandescent songs that enchanted pretty much everybody – hippies and new suburbanites, Vietnam protesters and war veterans.

And though those songs have been canonized as individual works, arguably the band’s most striking accomplishment is the way its music registers now – as a set of brilliant, interconnected flashes, elements in a mythology. We smile when any of Creedence’s songs leap from the radio, maybe at the beach — because they’re great songs, and also, possibly, because the sound puts us in close proximity to the mystical realm Fogerty and crew conjured like a magic trick, over and over again.

The Sound

What became the Creedence “sound” began in a junior high school in El Cerrito, California. Fogerty, drummer Doug Clifford and Stu Cook, who started on piano and switched to bass later, ran in the same circles, eventually becoming friends based on the music they liked, playing assemblies and dances as high school students. They discovered Chuck Berry and Carl Perkins and Elvis Presley together. They learned the basics of theory together. They each grew separately on their instruments – John Fogerty was obsessive about capturing riffs and phrasing tricks from Berry and Howlin’ Wolf records note for note – but learned the delicate art of being in a band by being in a band together.

It seems obvious to say it, but: When musicians play frequently together, cohesion develops. And trust. First in the Blue Velvets and then the Golliwogs, the members of Creedence learned how to take chances as a unit, and how to recover, together, when things went off course. They survived turbulent gigs and developed the intuitive sense that all great bands share. Fogerty recalled the early dynamic this way, in Hank Bordowitz’ history of CCR, Bad Moon Rising: “We were just all on the same wavelength, really.”

That’s audible, from the very beginning. Drop in on “Suzie Q” or anything from the self-titled debut album and what first captivates is the groove: How relaxed it is, how much space there is within it, how the recurring guitar phrase stings in slightly different ways as the song unfolds. These players are not merely copying the Dale Hawkins version — using its outline as a general guide, they go off into a rhythmic pocket that is thicker and nastier, and also more streamlined. Heavy and light at the same time, it slithers and slinks in ways that get people moving before they’re even aware they’re dancing. Where other rockers chased the showboating blaze of electric blues, this band preferred a subversive emphasis on rhythmic basics, trusting that the elemental, nothing-fancy pulse would create a kind of hypnotic intensity.

And if for some reason that didn’t work, the heat shimmers and surreal waves of tremolo coming from John Fogerty’s guitar would probably take care of it. Fogerty and his rhythm guitarist brother, Tom, found ways to gently underscore a song’s vibe without adding more information. Like so many of the bluesmen they idolized, Creedence used tense single notes and hovering chordal drones, along with echoey reverb and other textures, to establish atmospheres that elude capture on the sheet music. The sounds are elaborate, sometimes epic. But they caught them on the cheap: Each of the first three records were made for less than $2,000.

The Songs

(Don’t see the playlists? Click through to listen on Spotify or on Apple Music.)

Fogerty seized on the atmospheric vibe of those first singles and used it to guide his songwriting – it became the DNA of CCR. “We stepped into the next dimension with ‘Suzie Q,’ ” he recalled to Michael Goldberg in a 1997 article. “It was obviously another place from where we had been for ten years.”

What followed was an unusual creative blossoming. Fogerty wrote image-rich songs in bunches – the three (!) albums released in 1969 contain not only the band’s most enduring single, “Proud Mary,” but “Born on the Bayou,” “Bad Moon Rising,” “Lodi,” “Fortunate Son” and “Down on the Corner.”

All of these, and the lesser-known album cuts besides, are streamlined and plainspoken, miles from the marathon guitar meanderings of acid-rock. Fogerty prized concision as a writer and as a guitarist — even when his band did “go long,” as on the 11-minute cover of “Heard It Through the Grapevine,” his solos begin with melodically memorable declarations, not torrents of shredding. Similarly, his compositions focus on crisp verses and big takeaway refrains. This forthright style sometimes contrasts powerfully with the arty cutting-edge, contemporaneous writing of The Beatles, Bob Dylan and others, who were opening up the architecture of pop through unusual chord progressions, torrents of lyrics, elaborate instrumental interludes and other, sometimes radical, alterations.

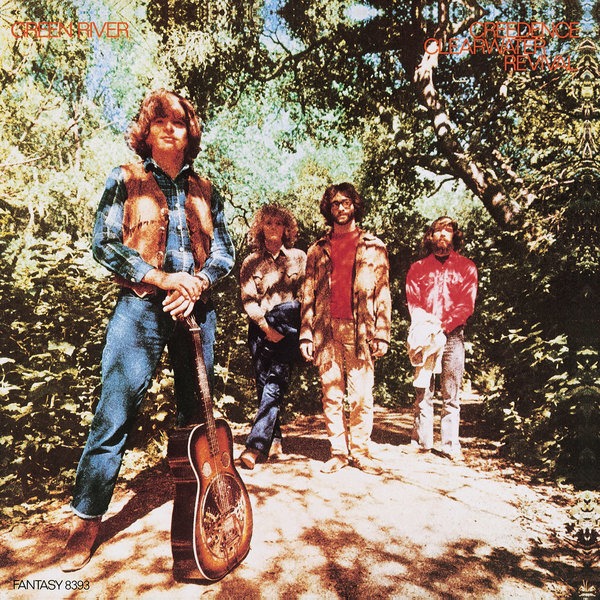

Creedence Clearwater Revival’s Green River was a landmark release for the band, but just one of three albums the group put out in 1969 alone. Courtesy of the artist

Fogerty stuck to bare-bones, barrel-strength basics, appropriating familiar templates from American folk and blues – the 12-bar blues form, the gospel jubilee, the one-chord drones, the Bo Diddley beat. He outfitted them with melodies that seemed almost eternal (see the hymnlike “Long As I Can See the Light”), or as joyous as children’s playground rhymes (“Down on the Corner”).

These types of songs can be tricky to write. Their cadences pretty much demand simple, honest lyrics; fancy metaphors and flowery images don’t really work. A student of the declarative style of Hank Williams, Fogerty mirrored the discipline of his music with terse lyrics. His characters talked the way people talk, and he placed them in situations that were usually relatable: In “Lodi,” a woeful tale of bad luck on the road, he pauses his story just long enough to acknowledge its universality, with the line, “I guess you know the tune.”

Crucially, Creedence avoided love songs — on purpose. Fogerty once explained that decision this way: “I heard love songs that didn’t really have much meaning. By the time I was 18, I made a conscious effort to steer away from that kind of songwriting.” He wrote instead about income inequality and entitlement (“Fortunate Son”), bad omens rising out of the swamp at night (“Born on the Bayou”), misfortune (“Lodi”), the relief of returning home from a tour (“Lookin’ Out My Back Door”), nostalgia for the giddy joy of early rock (“Up Around the Bend”), the frantic pace of modern life (the surprisingly prophetic “Commotion”). There are a few relationship songs on the records, however; one of the most memorable, on Green River, is “Wrote a Song for Everyone,” in which he marvels at how a songwriter can communicate profound ideas to the world while struggling to have an ordinary conversation with his partner.

Legacy

The story of Creedence Clearwater Revival – a word-salad name inspired by a friend of Tom’s named Credence and a line from a beer ad, combined with the band’s ersatz mission statement – has its share of typical classic-rock plot points. There have been multiple lawsuits, including one where Fogerty was accused of plagiarizing himself. The band members have squabbled for decades, acrimony that spilled over into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony in 1993. They’ve also been lionized by successive generations of artists who drew inspiration from the band – including Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty and Kings of Leon.

At least some key historical details are getting long overdue clarity. Creedence was one of the headliners at Woodstock ’69, but it declined to appear in Michael Wadleigh’s myth-making concert film, and a only a few audio tracks from the performance have been released. The circumstances of the show are partly to blame: The band had been scheduled to go on at 10 p.m., but the Grateful Dead’s set went hours long, and as a result Creedence began after midnight on Sunday, August 17, after many festivalgoers had returned to their tents.

The members of Creedence Clearwater Revival during a street performance and photo shoot in Oakland, Calif. for the band’s Willy and the Poor Boys album, also released in 1969.

CREDIT: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Fogerty has maintained, over the years, that those conditions affected the band’s performance. At the time, he said no to the filmmakers who wanted to use “Bad Moon Rising” because, as he recently told Billboard, “I just didn’t feel it was our best work.” His position on the release of audio from the Woodstock performance has shifted, he explained to Billboard: “Maybe around the late ’80s I began to think that, historically, it is what it is. It doesn’t matter if it’s well done or not well done, it became more a fact of history.” As a result, today (August 2) Concord is releasing the complete Creedence performance from Woodstock. It joins expanded anniversary editions of Bayou Country, Green River and Willy and the Poor Boys that each contain spirited live versions of some tracks.

Listening to those 1969 releases in chronological order, you can’t escape this band’s uncanny, warp-speed development – it’s one of the most dramatic evolutionary bursts in the history of popular music. The individual songs are plenty impressive, even the ones that have been burned into memory through overexposure. But it’s the totality of the output – and its interrelated and multi-dimensional sound-world – that emerges as a freakishly rare achievement.

Lots of acts managed a long string of hits. Very few were able to thread that string into a coherent and sustained evocation the way Creedence Clearwater Revival did. The songs offered scenes of placid rural life far from the purview of most pop – peering into shadowy swamps and bayous populated with all manner of creatures, characters with deep flaws and big hearts. Fogerty told Musician magazine’s Paul Zollo in 1997 that his breakthrough in that regard came late at night, during a period when he was struggling with insomnia.

“I was probably delirious from lack of sleep. I remember that I thought it would be cool if these songs cross-referenced each other. Once I was doing that, I realized that I was kind of working on a mythical place.”

Out of that place came a series of deceptively simple songs that stand alongside the works of Mark Twain and William Faulkner – musical-literary inventions that conjure the idyllic waters and mists and wildness of a remote America, and in the process, reveal clues about the whole country’s soul.