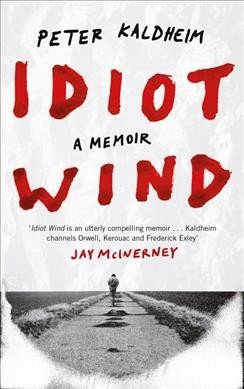

BOOK REVIEW: ‘Idiot Wind’ Tells A Personal Tale Of Journeying From Addiction To Recovery

BY MARTHA ANNE TOLL

I’m not sure I would have argued for another memoir in which a white man’s life implodes from alcohol and cocaine addiction. But now comes Idiot Wind by Peter Kaldheim, its title from the Bob Dylan song, with something to offer.

It’s January 1987 in Greenwich Village and a wicked blizzard is blowing through town. Kaldheim is down and out, having hit rock bottom at age 37. He’s burned through two wives, the second of whom died two years earlier from an aneurysm. Kaldheim is plagued with nightmares, drowning in shame that he didn’t attend her funeral. He’s on the run from his coke dealer, who doesn’t suffer swindlers gladly. Catching the last bus out of New York, he finds himself headed for Richmond.

Kaldheim channels his inner Jack Kerouac to guide him, and conjures additional substance-abusing, macho, white writers. Frederick Exley, Jay McInerney, Ernest Hemingway, Henry Miller, and others make appearances. Perhaps as a consequence, Kaldheim’s language can feel dated. A lover 10 years his senior is a “cougar,” and a fellow Rikers inmate who’s Italian is jarringly, “the guido.” Negotiating to drive a man’s car, Kaldheim admits he’s lost his driver’s license and is afraid he’s “queered the deal.” Ouch.

Idiot Wind

A Memoir by Peter Kaldheim

Fortunately, Idiot Wind picks up steam on the road, with some train hopping thrown in. Vietnam hangs like a shadow on the highways; multiple drivers suffer from service in the war. The generosity of both these drivers and other travelers pushes Kaldheim toward recovery.

In Richmond, the mentor of a friend floats Kaldheim the cash “that saved” his life. In a flea-bag motel, Kaldheim finds a sympathetic ear in a “fellow junkie.” He’s in from the cold and relatively safe. The universe provides advice on changing his life: Start “with empathy, with loyalty, with charity.”

Kaldheim plans to go west, but not before he thumbs his way to Florida. He gets there in short hops, his first ride from a rotund, civil war re-enactor who dreams of dying of gut-shot on every Confederate battlefield. He feels sorry for the kid driving him to Fayetteville, North Carolina, who’s facing jail time for violating probation on trumped up charges from a car accident. He deeply appreciates the tips he receives — suggestions on truck stops — as well as coffee and food, and occasional spending money.

Between rides, Kaldheim fills in his backstory: his childhood in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn; his severe father who worked “precision-grinding components for navy helicopters.” His two brothers, who also struggled with impulse control and substance abuse. As a kid, Kaldheim couldn’t help noticing that his friends’ “mothers weren’t wearing their bathrobes at four in the afternoon, or doing household chores with one hand while clutching a can of beer in the other.” He recalls his mother with fondness and tips his hat to her priest brother who inspired him to write.

When the promise of a job in San Francisco falls through, Kaldheim heads for Portland, Oregon. After being chastised for taking a second helping at dinner from an Idaho couple who can ill afford it, Kaldheim realizes that poverty has turned him “feral, like a stray cat who never knows when the meal is coming.”

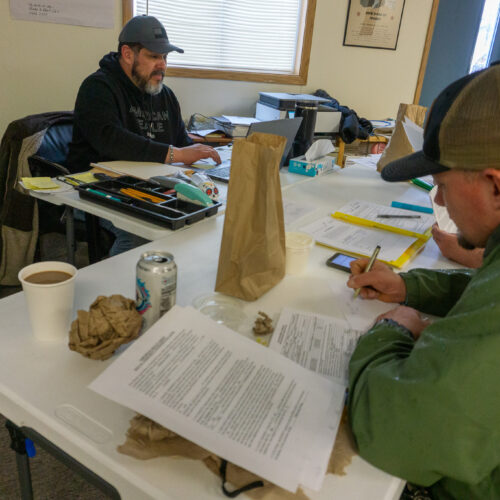

In Portland, Kaldheim befriends John, who gives him the homeless man’s guide to the city, including the “Stab Lab” where he sells his blood for cash. Kaldheim details Portland’s rich array of social services, which take on a moral dimension in today’s climate. These services are accessible, generous, and life-saving. Kaldheim is rescued with Food Stamps and other benefits — including housing — and an employment opportunity that enables him to jumpstart his life. He heads to Yellowstone for the summer, and in two short years becomes head chef at a park facility.

Reflecting America’s long romance with the road, Kaldheim looks longingly through the rearview mirror, nostalgic and proud, but also mourning his losses: his inability to renew a relationship with his estranged parents; and decades of separation from his brothers. He’s traveled a long distance — and not just geographically. From Catholic boarding school, to holding three jobs in order to graduate summa cum laude from Dartmouth, to torching a promising publishing career, to reconstructing his life on the cusp of middle age, Kaldheim wears the scars of a lifetime.

An afterword skims the years between his arrival at Yellowstone and the present, briefly covering Kaldheim’s cooking career, his third marriage — not without serious road bumps — and his eventual reconnection with his brothers.

Finally, there’s his editor friend Gerry [presumably Gerald Howard to whom the book is dedicated, along with Suzanne Williams] whose decades-long campaign to persuade Kaldheim to render his road notes into a memoir culminated in this book.

“Once the bridge is burnt, every addict becomes an island, no matter what John Donne says,” Kaldheim opines at his nadir. Even if we weren’t in need of another road-trippy-addiction memoir, Idiot Wind recounts Kaldheim’s very human efforts to swim to shore with compassion and gratitude.

Martha Anne Toll is the Executive Director of the Butler Family Fund; her writing is at www.marthaannetoll.com, and she tweets at @marthaannetoll.