Washington’s Changed Presidential Primary Means New Strategy For Candidates Like Bernie Sanders

Read On

BY TOM JAMES / AP

It’s a cloudy weekend morning at a farmers’ market in a leafy suburb east of Seattle, and Bernie Sanders’ volunteers are out in force.

Along with traditional campaign materials, they have what they say might be the next best thing to the candidate himself: a life-size cardboard figure for selfies.

But when a passerby expresses interest in Sanders’ policies, the volunteers are all business: “Brochures, brochures!” says Supreet Kaur, a local organizer for the campaign, as she rushes back to the table and grabs printouts.

Washington is one of 10 states where the Democratic Party is switching to a primary-only system ahead of the 2020 election, and Sanders’ campaign is hitting the state with an early volunteer push. Sanders easily won the 2016 Washington caucus, but the state’s shift to a primary presents a challenge for his campaign: converting the passionate caucus support he enjoyed in the last election to broader turnout in 2020.

“It’s a question of depth versus breadth, said Mark Smith, a political science professor at the University of Washington. “Caucuses pick up depth of support, but primaries tend to pick up breadth.”

Claire Sandberg, national organizer for Sanders, wouldn’t provide an exact number but said in June the campaign has a larger presence in Washington than at the same point in 2016, with “hundreds” of volunteers.

Altogether, it marks an early start in the state, where few other campaigns have launched direct-to-voters efforts ahead of the March 10 primary.

“We haven’t seen much public engagement in Washington yet,” said Will Casey, a spokesman for the state Democratic Party, who added he expects other campaigns to ratchet up their local presence in fall.

At least in the Seattle area, the Sanders’ volunteers appear to already be at work. Jan Hickling, who started a Facebook group in nearby Renton and said Sanders’ 2020 campaign was her first, said that later in July her group would put on its biggest public outreach event yet: hosting a manned tent at a festival for three days.

The campaign is also fielding a web app for volunteers, essentially allowing any interested supporters to be instantly trained in how to canvass — and potentially cutting out much of the traditional early role of paid campaign field organizers.

While Sanders won Washington’s 2016 Democratic caucuses, the results from the state overall point to a broader challenge potentially facing him this year.

In 2016, along with binding caucuses, Washington featured a nonbinding primary, and the results were sharply divided: Sanders won the caucuses by 46%, but lost the popular-vote primary to Hillary Clinton, by about 4%.

The split, Smith said, highlighted the difficulty of turning passionate supporters willing to attend a weekend event into the numerical strength to beat a candidate with broad name recognition, who can persuade even less-invested supporters to cast a primary vote.

Sandberg noted the campaign effectively withdrew much of its on-the-ground presence from Washington following the state caucuses that year. But she also acknowledged engaging Washington voters differently in the earlier race.

At the time, she said, the campaign saw the efforts of Washington volunteers as best directed outside the state.

“We were asking them to sign up to host phone banks or to attend phone banks to make calls into Iowa,” Sandberg said.

Sandberg described a 180-degree turn for the campaign in the state ahead of the 2020 election.

Along with the volunteer push, a web portal the campaign is calling the “Bern App” allows volunteers to be remotely trained via a short video — potentially streamlining what has traditionally been a time-consuming task for campaign field organizers.

The app, accessed on a phone or tablet, lets volunteers look up voters they meet. After looking up a voter, canvassers can enter information about them including survey responses, and instantly sign them up for email and text alerts.

Using the app and community events, Sandberg said, the campaign is aiming to mobilize the largest possible number of voters for a sustained push in the state.

And, Sandberg said, unlike in 2016, this year that energy is focused on influencing other Washington voters, not out-of-state undecideds.

How that translates nationally is an open question, said Smith, of the University of Washington, given Sanders’ performance tended to be weaker in primaries across the board.

One example: Nebraska. Like Washington, that state also ran both a Democratic primary and caucus, and while Sanders supporters brought home the state’s caucus-bound delegates, Clinton won the popular vote.

“Sanders dominated the caucus,” said Vince Powers, who chaired the Nebraska Democratic Party from 2012 to 2016. Sanders overcame his initial name-recognition deficit there, Powers said, but Clinton still was able to get more supporters to the polls.

The same split was reflected in results nationwide, with Sanders winning in more than three-quarters of the states that held caucuses in 2016, but only about a quarter of those that held popular-vote primaries.

Still, Sandberg said she’s optimistic, in part because getting people to vote is a simpler task than getting them to a caucus, and because the campaign won’t have to struggle with name recognition this year.

“It’s work that we don’t have to do,” Sandberg said.

Copyright 2019 Associated Press

Related Stories:

Experts Call It A ‘Clown Show’ But Arizona ‘Audit’ Is A Blueprint For Future Disinformation Campaigns

At a basic level, it’s a victory for those looking to sow doubt in the 2020 election results just to have them still being litigated six months after Election Day. To be clear, Maricopa County’s election results have already been audited multiple times by companies with experience in the field, with no problems being uncovered.

Washington Voters Said ‘No’ To A Constitutional Amendment. Now There’s A $15 Billion Problem

It was a little-noticed constitutional amendment to allow for the investment of long-term care trust fund dollars in private stocks. Voters soundly defeated the measure 54 to 46 percent. Now comes the surprise cost of that under-the-radar vote: an estimated $15 billion.

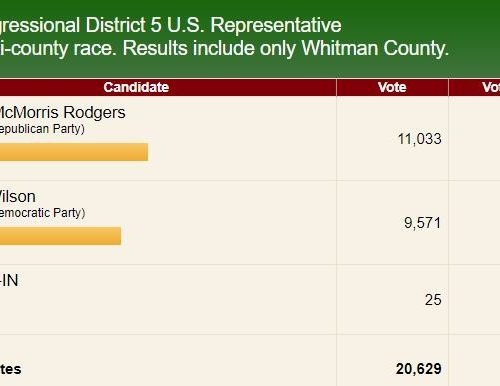

Incumbent’s Advantage: Why Whitman County Votes For Biden And Inslee, But GOP For Congress

Even in a county that generally supports Democrats for governor and president, Republican Congresswoman Cathy McMorris Rodgers won. In fact, she got more votes in Whitman County than Jay Inslee did for governor.