Hot Potato! The Science Of Getting Delivery French Fries Right Is Being Honed In Washington

READ ON

Home-delivered fast food is a booming global business, but when it comes to French fries, there’s a hitch.

They often get soggy on the ride. So now, top fry-makers are racing to perfect a crispy fry that can survive a 15-minute ride with a food delivery service.

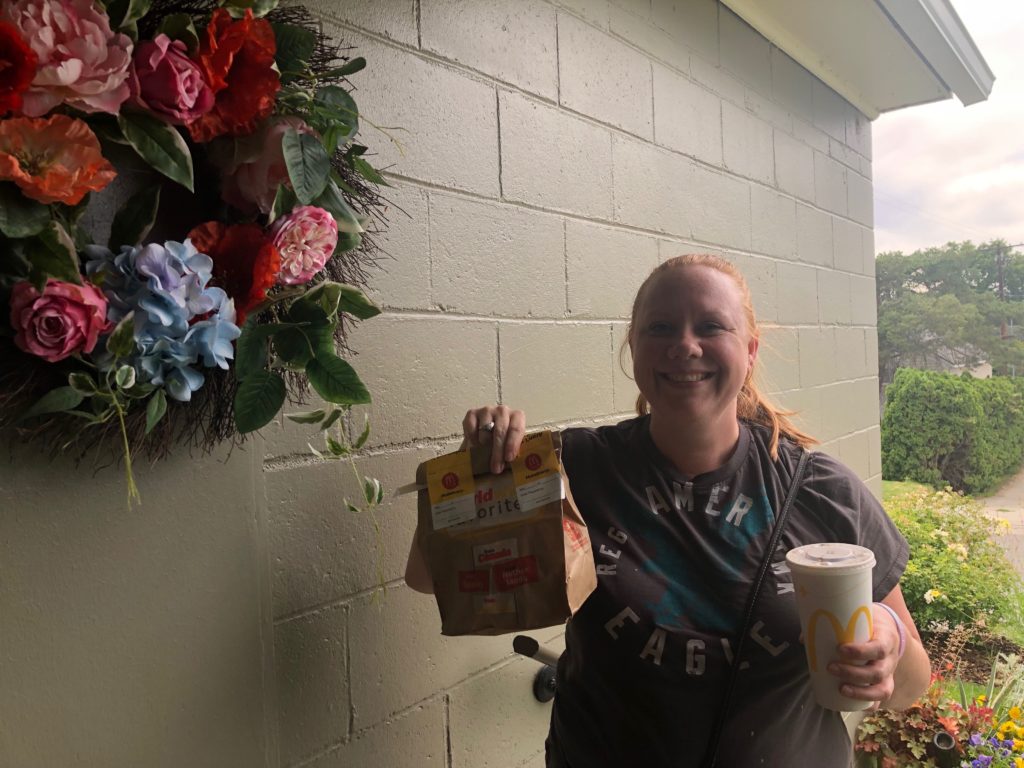

To truly get the facts on delivered French fries, I ordered some. My dog, Poa, starts barking when Uber Eats driver Crystal Begallia comes to my door. And I ask her if she stresses over delivering cold and limp fries to her customers.

“I get kind of worried,” Begallia says. “Especially if I pick up food from one of the bigger restaurants, and they are spending quite a bit of money. Hopefully it’s still hot when I get to you.”

Food delivery driver Crystal Begallia delivers McDonald’s fries and cheeseburgers to Anna King’s door for a public radio experiment. CREDIT: ANNA KING/N3

Companies right here the Northwest are frying up a crisp solution to this soggy situation.

One reason fries can lose their crunch is because they’re often delivered in closed containers.

“Because you’re sealing them in like a sauna,” says Deb Dihel, head of innovation for large potato processing firm, Lamb Weston. “And they just get soggy really quickly. So, it’s like the worst case scenario for a French fry.”

Lamb Weston is based in Eagle, Idaho — that state famous for its potatoes — but has major processing plants and an innovation center in Washington’s Tri-Cities area.

Dihel first saw what happened to delivery fries in China five years ago. And she noticed restaurants there were putting hot fries into large clamshell containers with burgers for delivery runs.

“I was like no, no, no! Don’t do that!” she says. “At least leave it open, like at least let the steam vent and not make the product soggy.”

Dihel says that once out of the oil, most fries can only stay crisp for 12 minutes max. So when she came home she set about trying to fix the problem. One solution: Changing how fries are made.

Deb Dihel is the head of innovation for Lamb Weston. She looks over some freshly fried Crispy on Delivery fries that she helped develop over the past several years. CREDIT: ANNA KING/N3

To show off several years of work, she opens a bag of frozen fries, right from the factory. She puts them in a wire basket and lowers them into hot bubbly oil in Lamb Weston’s Richland test kitchen. They’ve been dipped in a special starchy batter. Most fries are dipped before they make it to you, but this is a new formulation. When the fries come out they have a lot of crunch.

They were still crunchy 30 minutes later, even at room temperature.

Fast Food’s Evolution

The other part of keeping fries crunchy on a ride is packaging.

Lamb Weston developed a special container perforated with holes that’s supposed to let enough steam escape without the fries getting cold. It’s a design that big restaurant customers can copy — and so can other packaging brands for themselves.

Innovating to meet the needs of busy consumers has always been part of fast food’s evolution, says Adam Chandler. He wrote the new book: Drive-Thru Dreams: A Journey Through the heart of America’s Fast-Food Kingdom. He’s not surprised that big potato is working to slay the soggy.

“Fast food really doesn’t seem to be the kind of food you’d like to eat when it’s older than five minutes,” Chandler says, adding that home delivery is “how people are eating now, so the market is going to respond to that problem.”

He says the fast food industry and fry factories have always worked to adapt over time to what Americans and the world wants.

Blair Richardson is CEO of Potatoes USA, based in Denver. CREDIT: ANNA KING/N3

“For instance McDonalds famously used to make their fries with beef tallow,” Chandler says. “While delicious, that was incredibly unhealthy.”

Now, he says, in response, most companies only fry in all-veggie oils due to U.S. consumers’ health concerns.

Reimagining Potatoes

At a popular fast food restaurant in Kennewick, Wash., I met Blair Richardson for lunch. Deft waitresses carry in baskets of burgers and fries on round trays. Richardson is the CEO of Potatoes USA, a trade organization based in Denver. Of course, he orders fries. Richardson says because delivery is such a fast-growing segment of the total market, fry makers and restaurants are trying to figure this out.

“We are reimagining how we can bring potatoes to consumers today, and we never stop doing that,” Richardson says. “If an industry stops doing that then they’re going to become irrelevant very quickly.”

Not far away, 24-hours a day, rivers of freshly-cut fries flow over conveyor belts inside Lamb Weston’s massive factory. Ideas are flowing at Lamb Weston, too. Deb Diher envisions something bold for the fries of tomorrow coming in the not-too-distant future: being loaded into self-driving cars with onboard air-fryer — and robots to do the frying.

Related Stories:

Frank Tiegs: A Northwest ag titan known by just his first name across the Northwest and nation has died at 66

At the top of a hill, a tractor with a 17-foot wide planter plugs seed potatoes into the sandy ground at the Ice Harbor Hilltop Farm east of Burbank. (Credit:

A glut of potatoes means big spud dump across the Northwest

Potatoes, fresh from the field, bump onto a belt before being transferred to a storage shed outside of Boardman, Oregon. (Credit: Anna King / NWPB) Listen (Runtime 1:10) Read About

Fries of the future could use less pesticides, water and be more resilient to climate change

Ken Luke, a manager with McCain Foods, shows off some of the old standby potato varieties, along with some of the new, like the fresh “King Russet,” at a recent