A Yield Curve Inversion Just Happened. It’s Done So Before The Last 7 U.S. Recessions

The floor of the New York Stock Exchange. An economic indicator known as the “yield curve inversion” hit the three-month mark, which has preceded the past 7 U.S. recessions.

CREDIT: Richard Drew/AP

BY BOBBY ALLYN & MICHEL MARTIN

Signs are pointing to a coming U.S. recession, according to an economic indicator that has preceded every recession over the past five decades.

It is known among economists and Wall Street traders as a “yield curve inversion,” and it refers to when long-term interest rates are paying out less than short-term rates.

That curve has been flattening out and sloping down for more than a year, raising worries among some analysts that investors’ long-term view of the market is not positive and that an economic downturn is looming.

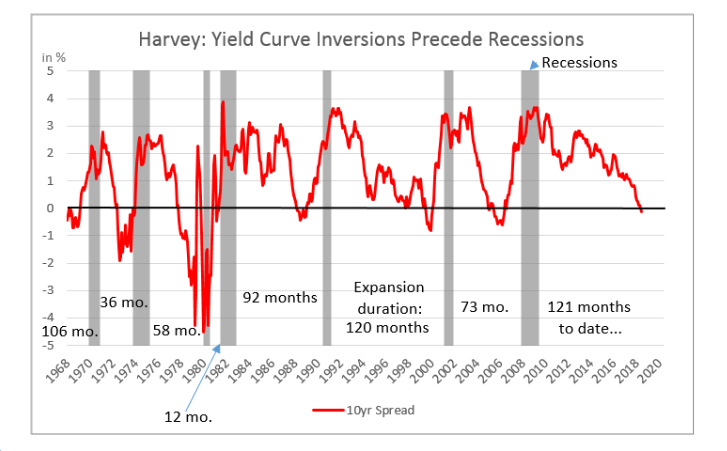

But on Sunday, an inauspicious milestone was achieved: The yield curve remained inverted for three months, or an entire quarter, which has for half a century been a clear signal that the economy is heading for recession in the next nine to 18 months, according to Campbell Harvey, a Duke University finance professor who spoke to NPR on Sunday. His research in the mid-1980s first linked yield curve inversions to recessions.

“That has been associated with predicting a recession for the last seven recessions,” Harvey said. “From the 1960s, this indicator has been reliable in terms of foretelling a recession, and also importantly, it has not given any false signals yet.”

Still, many economic forecasters do not see a recession on the horizon.

For instance, Randal Quarles, the Federal Reserve’s vice chairman for banking supervision, has said that the gap between short- and long-term interest rates does not mean the U.S. is moving toward a recession.

In a 1986 dissertation, economist Campbell Harvey identified an economic indicator that would precede the next seven recessions. That indicator, known as “a yield curve inversion,” now forecasts a coming U.S. recession. Courtesy of Campbell Harvey

And then there is a sea of bright economic news setting the backdrop for the yield curve inversion hitting its three-month mark: unemployment is at a near historic low, the stock market is going strong. The S&P 500 is up 17% for the year. And while some economists say the pace of growth may be slowing, the consensus view is that a dramatic economic plunge is not on the horizon.

But Harvey says no single economic predictor has the impressively prescient track record of the yield curve inversion.

“Yes, the economy looks good right now,” Harvey said. “But the yield curve is about the future,” he said. “It captures the expectations of the broad market in terms of what might happen in the future.”

Might a whole quarter of an inverted yield curve become a self-fulfilling prophecy?

“Perhaps,” Harvey said.

Consumers could see the data point as a red flag and pull back on spending, or corporations may view the sloping yield curve and decide not to make investments or hire new employees.

“I look at it more in terms of risk management. This is an important piece of information. It helps people plan,” Harvey said. “It enhances the possibility that we have a soft landing, not a hard landing, like a global financial crisis.”

If the idea of an inverted yield curve remains hard to grasp, Harvey says think of it this way: a yield curve is the difference between a short term cash instrument, like a three-month government bill, compared to a long-term one, such as a 30-year government bond. When the short-term ones are paying out more than the longer-term ones, something is wrong. And economists call it an inverted yield curve.

Or, Harvey said, think of a certificate of deposit at a bank, better known as a CD.

“If you lock your money up for five years, you expect to get a higher rate than, say, locking it up for six months,” he said.

“But in certain rare situations, things get backwards and it turns out the long-term interest rate is lower than the short-term rate, and that’s called an inverted yield curve. That’s exactly the situation we got now, and it is a harbinger of bad news.”