In A Break From The Past, Oregon Sheriffs Change Their Approach To Gun Laws

READ ON

BY JONATHAN LEVINSON / OPB

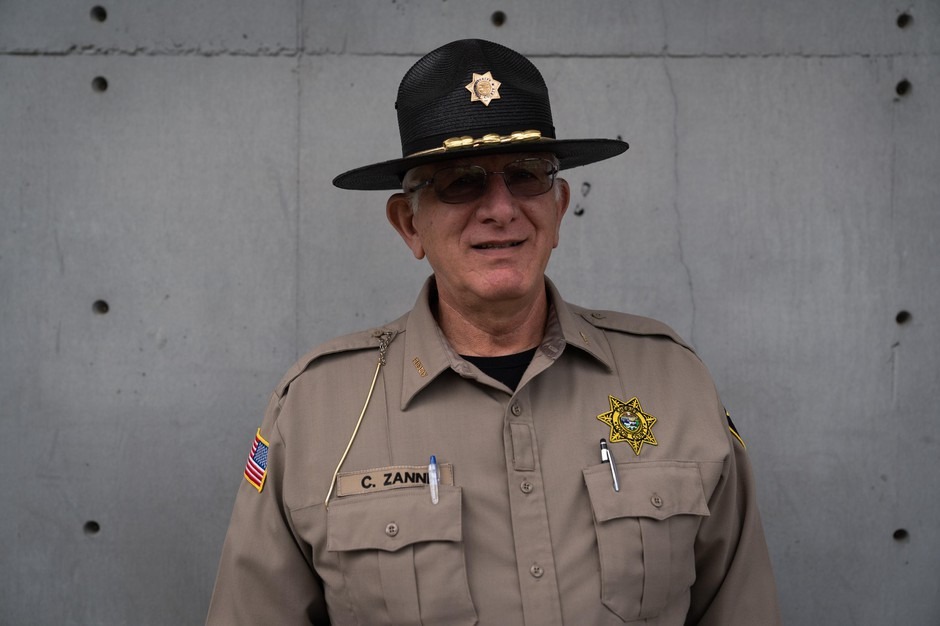

Early this past June, Coos County Sheriff Craig Zanni was in his Coquille, Oregon, office fielding an email from a sovereign citizen. The sender was claiming that the Oregon state government doesn’t have grounds to operate because it can’t provide him with a copy of the 1859 state constitution.

Sovereign citizens reject the legitimacy of the state and federal government. All of it: taxation, currency, the courts and, of course, gun laws.

Zanni says a significant number of people in his southern Oregon county, population 69,000, hold similar views. Except for the rare exception, he says they’re not dangerous.

“Most of them are reasonable people,” he said. “Like most people, I just want to live my life and be left alone, so I understand that.”

But the FBI calls them anti-government extremists.

Along with national militia organizations like the Oath Keepers and Three Percenters (whose core beliefs overlap significantly with sovereign citizens), their ideology has experienced a resurgence since President Barack Obama was first elected in 2008.

Their outsized political influence was on full display in recent years when Oregon sheriffs grabbed national headlines for refusing to enforce proposed state and federal gun laws, a concept plucked right from the militia playbook.

But as sheriffs in other states try the same thing, Oregon sheriffs say they have already realized that strategy doesn’t work.

Sheriffs Dig In

In 2013, eight Oregon sheriffs, led by Linn County Sheriff Tim Mueller, sent letters to the Obama administration saying they wouldn’t enforce new federal gun laws.

Mueller also said he wouldn’t allow federal law enforcement agencies to enforce federal laws either.

“Nor will I permit the enforcement of any unconstitutional regulations or orders by federal officers within the borders of Linn County Oregon,” Mueller wrote.

Two years later, in 2015, the Oregon legislature passed a bill requiring background checks for private gun sales. And again, Oregon sheriffs dug in.

So it was already a well-worn path when sheriffs in Washington and Colorado started making similar assertions earlier this year.

Federal Law Is Supreme

The false idea that the sheriff reigns supreme was popularized by Constitutional Sheriffs and the Peace Officers Association founder and former Arizona Sheriff Richard Mack.

“The sheriff is the most powerful law enforcement officer in the country, no one supersedes his jurisdiction,” Mack falsely claimed in an interview with the Oath Keepers militia. “The President of the United States cannot tell your sheriff what to do.”

Portland State University professor of political science Chris Shortell says that is at odds with the U.S. Constitution.

“Most notably the supremacy clause,” said Shortell, “Which lays out that when there’s a conflict between federal law and state law, federal law is supreme.”

But Shortell says these sheriffs are right on one narrow point.

In the 1997 Supreme Court decision Printz v. United States, the court said the federal government can’t force state officials to enforce federal laws.

“That doesn’t mean that the existence of federal laws can’t constrain the actions of state officials,” said Shortell.

So if the federal government bans certain kinds of firearms, that law would apply to each state and all of its counties.

And while there may be some wiggle room in the state-federal relationship, that isn’t the case with the county-state relationship.

“Counties are entirely a construct of states,” explained Shortell. “States create them, states could eliminate them, states can redraw their boundaries and as such, they are treated as simply a part of the state.”

Coos Bay, Oregon (left) and Drain, Oregon (right). Rural Oregon counties have taken enormous financial hits as demand for timber has declined in the wake of the housing crisis. Cash strapped sheriffs say they don’t have the resources to enforce new gun laws. CREDIT: JONATHAN LEVINSON/OPB

A lot of this is about politics. Sheriffs have to win elections if they want to keep their jobs. And in rural counties with small populations, a politician can’t afford to ignore organized voters.

“A small group of very engaged voters can have an outsized impact,” Shortell said, “particularly in elections that are what we would call off cycle.”

Constituents were cheering them on when Oregon sheriffs said they wouldn’t enforce the 2015 background check bill. But while it played well with voters, the law doesn’t actually involve sheriffs.

In Oregon, if you want to sell a handgun to a friend, you go to a gun store, pay $35 for a background check with the state police — not the local sheriff — and you’re on your way. Unless the gun is stolen or one of you is a felon, the sheriff wouldn’t be involved.

Political Migration

In some parts of rural Oregon and the Pacific Northwest, the actual makeup of the electorate has changed too. As the militia movement gained traction in the ‘70s and ‘80s, the Pacific Northwest was an attractive destination with its vast, sparsely populated and affordable land.

“Specifically, a lot of these groups looked to … places like Eastern Oregon, Eastern Washington and Idaho because land was relatively cheap,” says Steven Beda, assistant professor of history at the University of Oregon. “So they could buy up land and build their own bunkers.”

Fast forward to the early 2000s, and families are leaving California in search of lower housing prices and cost of living. Many are again looking to rural parts of the Pacific Northwest, particularly Eastern Oregon and Idaho.

“I think what we’re seeing now … is people moving to these places because their perception of these places is they are overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly conservative,” said Beda.

Beda says if enough white conservative Californians move to rural counties because they believe it reflects their values, then it will ultimately reflect their values.

A New Approach

Last November, Democrat Kate Brown won her re-election bid for governor and Democrats won supermajorities in both houses of the Oregon Legislature. Brown and many legislators had campaigned on passing stricter gun laws, and soon after taking office they set about delivering on their promise.

While sheriffs in other states were refusing to enforce new laws this winter, a raft of new gun laws were making their way through the Oregon Legislature. But this time, Oregon’s sheriffs were quiet.

That may be because in the past few years things have changed in parts of rural Oregon.

“I think the militia thing has really dropped off,” said sheriff Zanni. “That became huge when President Obama was first elected.”

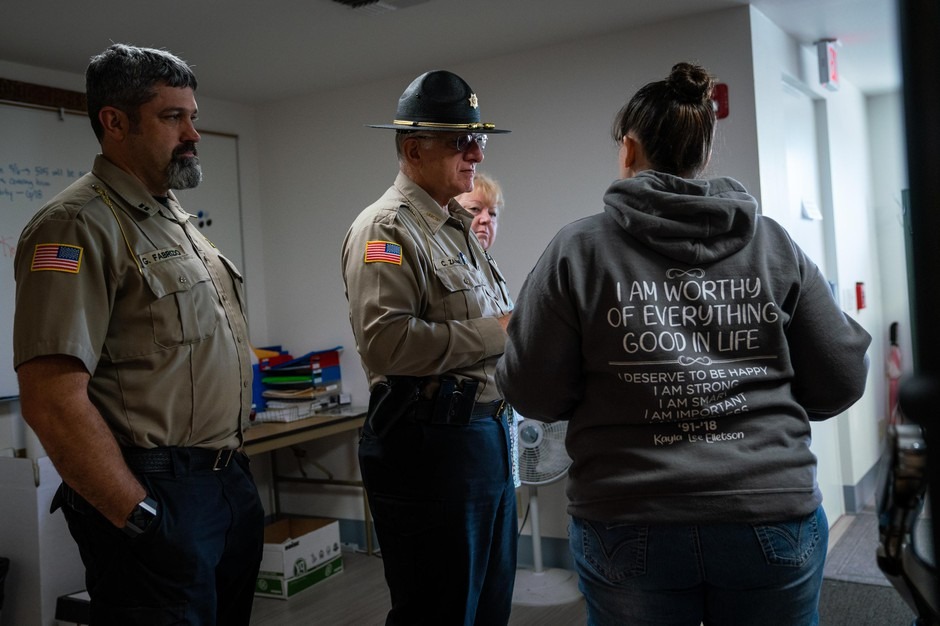

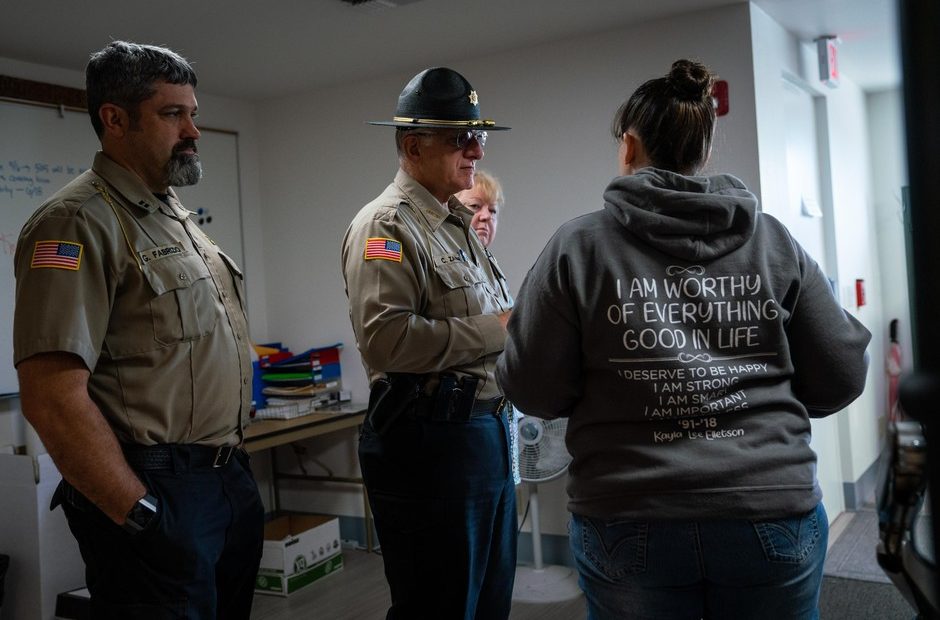

Coos County Sheriff Craig Zanni, center, speaks with Sheriff Department dispatchers on June 6, 2019, in Coquille, Ore. CREDIT: JONATHAN LEVINSON/OPB

He says his constituents are still worried about new gun laws but he’s noticed less vitriol and more patience. Gun owners spent eight years worrying that the Obama administration was coming for their guns. But no one came for their guns.

“I think over the years that it’s kind of like … the world hasn’t come to an end, so it’s not quite as big a deal,” Zanni said.

This year the Oregon State Sheriff’s Association changed how it approaches the state government as well.

“I think we have made a concerted effort to have a good relationship with all the legislators,” said executive director John Bishop. “Going in and beating heads and saying ‘You’re stupid and we’re not going to do this’ doesn’t work anymore.”

He says sheriffs have the expertise that can improve legislation. But they have to be in the room to share it.

Bishop also talks to his counterparts in other states.

“Now as far as Colorado and Washington, I think they’re just sort of a little bit behind this,” he said.

Bishop says he thinks other states will come to the same realization as well.

Guns & America is a public media reporting project on the role of guns in American life.

Copyright 2019 Oregon Public Broadcasting. To see more, visit opb.org

Related Stories:

Tacoma police chief back after weeklong investigation

After a week of administrative leave, Tacoma’s police chief is back on duty.

Tacoma City Manager Elizabeth Pauli placed Tacoma Police Chief Avery Moore on leave last week. In a statement released on Wednesday, Pauli wrote that she conducted a fact-finding investigation into personal use of a city asset. The statement did not specific what the city asset, or costs associated with it, were.

Local control, better recognition of tribal police could solve more MMIP cases

Leotis McCormack answers the phone at his office at the Nez Perce Tribal Police Department in Lapwai, Idaho. (Credit: Lauren Paterson / NWPB) Listen (Runtime 4:02) Read More than 17

Lawyer for suspect in Idaho student killings asks judge for police training records

Bryan Kohberger enters the courtroom for a hearing Tuesday, June 27, 2023, at the Latah County Courthouse in Moscow. (August Frank/The Lewiston Tribune via AP) Listen (Runtime :55) Read At