All He Wanted Was To Be Free: Where Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Western Stars’ Came From

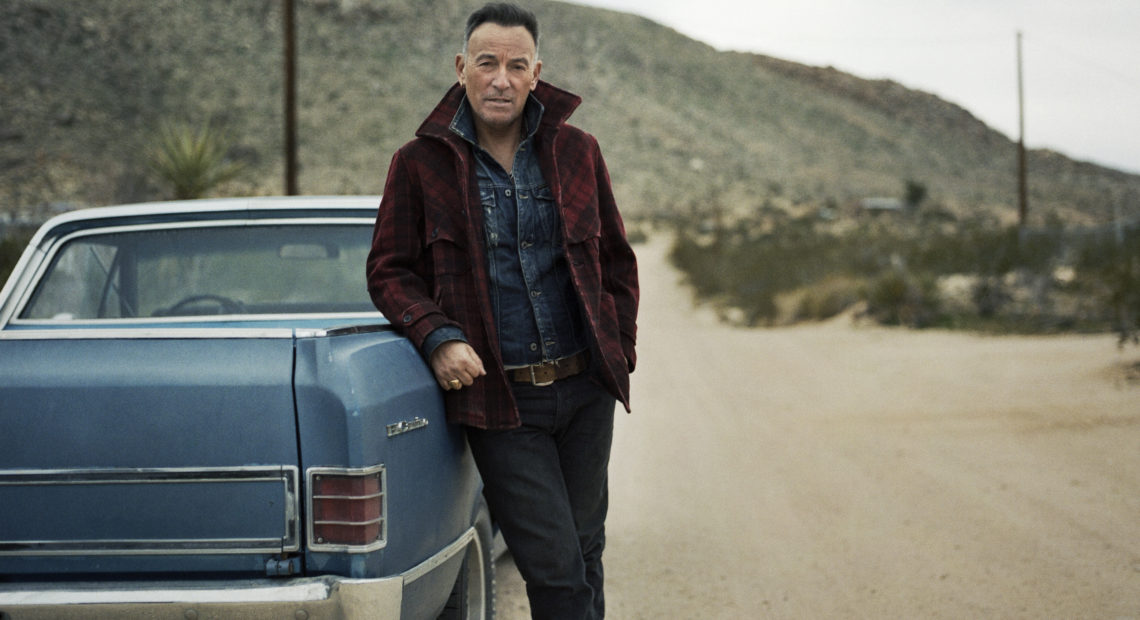

PHOTO: On Western Stars, by honoring a musical legacy he loves, Springsteen finds new life in familiar stories. Courtesy of the artist

BY ANN POWERS

In 1981, after reading the paraplegic veteran Ron Kovic’s memoir Born on the Fourth of July, Bruce Springsteen staged a concert to benefit the advocacy group Vietnam Veterans of America. For the encore, he played a song he hadn’t performed before and hasn’t since. Roger McGuinn’s “The Ballad of Easy Rider” is a slow-rolling meditation on freedom’s attractions and its costs that McGuinn wrote after Bob Dylan offered him one couplet scrawled on a napkin: “The river flows, it flows to the sea/wherever that river goes, that’s where I want to be.” The song soundtracks an idyllic early scene in Dennis Hopper’s hugely influential 1969 road movie Easy Rider, as he and his co-star Peter Fonda (playing drug-dealing hippie outlaws named Billy and Wyatt) ride their motorcycles through a magical Southwestern landscape. It plays again over the closing credits, after Billy and Wyatt have been shot dead on a Louisiana back road by a passing redneck. Springsteen’s cover, according to his biographer Dave Marsh, was a nod to veterans’ love for the song, with its undercurrents of social exile and personal loss. Reworking it in concert, the Boss also paid tribute to a type of hit he often emulated on his own albums: the big, highly produced existential rock ballad, whose rise dates from around the time Easy Rider redefined the road movie as an expression of young people’s confusion and weariness as the 1960s ended and the Nixon era began.

It’s possible to trace the path taken by Springsteen’s new, highly orchestrated solo album, Western Stars, all the way back to his decision to cover “The Ballad of Easy Rider” thirty years ago. McGuinn’s rendition in the film is relatively spare, but his band The Byrds released a version featuring a string section, added by producer Terry Melcher, to up its odds of becoming a Top 40 hit in the style of popular crooners like Glen Campbell. In Springsteen’s take (findable on YouTube) Danny Federici’s trickling piano lines fill in for the strings, echoing their presence in a ghostly but convincing way. Now, all this time later, Springsteen has found his way to those strings.

Springsteen’s embrace of what became known around 1966 as “orchestral pop” has struck many who’ve heard Western Stars as a major turn, one perhaps inspired by his recent time spent on Broadway, the home of show tunes. But Western Stars is not the Boss’s West Side Story. Instead, it connects to a different sensibility altogether, one closer to Easy Rider and other cinematic landmarks of the imploding 1960s cultural revolution. More pointedly, Western Stars connects to a certain stream of pop balladry that emerged in tandem with Hollywood’s turn toward hippie antiheroes – songs that ask a question similar to the one haphazardly posed by Easy Rider: Who gets hurt when people, especially men, try to be free? “All he wanted was to be free, and that’s the way it turned out to be,” McGuinn sings in “Easy Rider,” contemplating the crash on the highway where Wyatt and Billy lay.

Writing in 1975, the film theorist Thomas Elsaesser coined the term “the pathos of failure” to describe the feeling movies like Easy Rider captured — the poignancy of modern masculinity’s fatalistic drift. In Fonda’s Wyatt, an American flag patch affixed to his motorcycle jacket, he saw a new kind of antihero. Leather-clad and slim, this “unmotivated hero” wanders the landscape not looking for anything in particular, but not really escaping either, just spinning wheels. His psychic exhaustion has no room for the driven energy earlier road-bound heroes possessed, whether they were the Wild West’s cowboys or the nervous escapees of film noir. Those characters usually met gruesome ends but still believed in themselves, or in trying, at least. The unmotivated hero has no hope, and no feeling that it matters whether he does or not. This attitude resonated at the turn of the 1970s, as a would-be cultural revolution gave way to the square realities of mainstream life: Nixonian politics, suburban sprawl, what Elsaesser called “stunned moments of inconsequentiality.” On Western Stars, in songs that aren’t particularly attached to a historical moment, Springsteen pursues a similar mood of anomie.

Masculine damage is one of Springsteen’s great topics, and it’s not at all surprising that he revisits it throughout Western Stars. Over the decades he has written hundreds of humbly nihilistic lines like the one that opens the album’s symphonic yet still somehow modest-feeling title track: “I wake up in the morning, just glad my boots are on.” Continuing his long line of unreliable narrators, the voices in these songs mostly belong to older inhabitants of unstable professions – the movie industry, songwriting, shift and contract work – who pine for more stable lives with the women upon whom they rely, but are convinced they can’t return to them. These characters are more seasoned versions of the petty street criminals of Springsteen’s early and mid-period work, kin to the broken soldiers and immigrant drug runners of his 1980s and 1990s albums, and also to the “I” he inhabited on his more autobiographical solo albums, expressing various states of mental unrest.

Springsteen often uses the ballad form to tell the stories of these unstable characters, and he’s challenged himself to keep the music fresh. On 1982’s Nebraska he recorded at home, by himself, producing a sound that some considered “folk” but which was closer to the work of edgy singer-songwriters like Townes Van Zandt. 1995’s The Ghost of Tom Joad conscientiously connected to folk traditions. More recently, he’s worked with pop-savvy studio men like Brendan O’Brien and Ron Aniello, who’s also behind Western Stars, dipping more than a toe in the classic pop sound he’s now fully embraced. Two of his best songs from this century, “The Wrestler” and “Girls in Their Summer Clothes,” could have easily appeared on Western Stars, with their stories of alluring ramblers who are starting to fade into the cultural background, set within sumptuous arrangements. This album feels like an extension of that work. His characters here voice a hard-won maturity, though most remain unfulfilled. Sometimes, as on the sanguine early single “Hello Sunshine,” they even are able to compromise their dreams and settle for a kind of happiness. They represent the imagined afterlives of the unmotivated heroes of Easy Rider, trying to figure out what their unexpectedly longer lives mean.

To find inspiration for stories like these, Springsteen looked not to the movies of his young adulthood, which usually ended in fiery explosions or shootouts or sudden cuts to black, but to the songs that brought the unmotivated hero’s voice to the radio in the same cultural moment. Early reviews of Western Stars note the sources: the songbooks of rock and soul-inspired 1960s and 1970s hitmakers like Jimmy Webb, Harry Nilsson and the team of Burt Bacharach and Hal David. Their songs don’t sound like they belong to outsiders: awash in violins and woodwinds, they claim none of the raucousness of rock and roll. But they express loss, and the state of being lost, as effectively as Easy Rider did in its more unhinged and violent way. “Everybody’s Talkin’,” written by Fred Neil and covered by Harry Nilsson in a version that became the theme for another key film of 1969, Midnight Cowboy, is a prime example. Neil’s original version was spare, but Nilsson’s adds strings, and they almost constitute a drone, creating an undertow that propels the guitar and lightly brushed drum and Nilsson’s slippery vocals down the river toward oblivion. “Everybody’s talkin’ at me,” he complains. “I can’t hear a word they’re sayin’, only the echoes of my mind.” The song is an expression of paranoia as much as it is a declaration of independence; it’s about pushing off, but never landing.

How did songs like this, so obviously about trouble and defeat, find a home at the heart of mainstream pop? Making losers beautiful, they poetically reinforced the anxieties many people were feeling about the costs of freedom. Vietnam was coming to its ugly end, and the kids who’d hoped to change the world were starting to feel the damage their more reckless moments had wrought. A beautiful arrangement could hold the dark emotions of those times in a comforting embrace. This paradoxical combination is still what resonates about these songs. It’s what brings the tears when we listen to the best songs by Jimmy Webb, like the soldier’s anguished self-elegy “Galveston” or the workingman’s crisis of faith “Wichita Lineman.” The pathos of this music resides in its blend of musical sophistication and lyrical rawness. This is what Springsteen finds on Western Stars. Maybe it felt like a chance to take a path he’d avoided as a young rocker more intrigued by soul music and then punk; maybe he also recognized an echo that resonates today — a comforting musical palette that offered room to ruminate at a historical juncture, like our own, imbued with anxiety. “Make it easy on me just for a little while,” Nilsson sings in “Don’t Forget Me,” another song that Springsteen might have spun while writing these. He’s begging a lover he’s probably wronged to put up with his pathetic ways, or at least his memory, for a little while; but he’s also defining what his song does for the listener, creating a velvet cushion upon which to rest while pondering rough realities.

It’s easy to make a playlist full of tracks like this from the 1960s and 1970, any of which might have been inspiration for Springsteen as he crafted Western Stars. (I’ve done so; the link is below.) Start with “Early Morning Rain,” written and recorded in 1966 by Gordon Lightfoot, one of the key figures in the mainstream folk revival, which embraced new sonic approaches – including string-kissed, Beatles-inspired arrangements – to render the sounds and stories of traditional music more accessible. The key line in Lightfoot’s song — “You can’t jump a jet plane like you can a freight train” – brings folk into the aerospace age, replacing the Woody Guthrie-era image of the wandering hobo with a less romantic one, of a traveler stranded by his own limitations within the cold confines of city life. Here, the drifter becomes modern. Folk rock offered many memorable takes on this figure over the years: the more sanguine one in Tom Rush’s “No Regrets”; the beautifully bitter “Good Time Charlie’s Got the Blues,” by Danny O’Keefe; the drugged-out version in John Phillips’s “Holland Tunnel”; Jackson Browne’s road dog considering his lot in “The Load Out.” This is the easy rider who makes it long enough to feel washed up. He shows up a few times on Western Stars: He’s the songwriter who didn’t make it in “Somewhere North of Nashville,” and the stunt man who’s feeling the pain of his injuries in “Drive Fast.”

Country music is another prime conduit for exquisitely rendered existential angst. In tandem with the blues, it developed as music’s repository of fully adult stories: It’s where divorce, parenting, aging and other complex topics are tackled, and where subjects age, too, facing the consequences they’ve generated. In the 1960s, as it intersected with folk and, more subtly, rock, country also explored the tension generated when unvarnished emotions met ornate orchestration. Stars like Kris Kristofferson, Glen Campbell, Charlie Rich, Ronnie Milsap, Bobbie Gentry and even Elvis Presley made powerful songs at this crossroads. So did Nashville-influenced rockers like Bob Dylan and Neil Young, whose “A Man Needs A Maid,” from 1972, is one the most vulnerable and disturbing musical expressions of the pathos of failure ever recorded. The lyric’s deeply vulnerable (and paternalistic) expression of masculinity’s emotional shortcomings – Young literally cries for a woman to help feed and clothe him, but then go away — gains its pathos from a grand orchestral arrangement. It’s a lot like what Springsteen reaches for on Western Stars – long-cultivated loneliness turned into high drama.

The crisis Young expresses in “A Man Needs a Maid,” like the one Springsteen’s faithless lover faces in “Stones,” doesn’t immediately seem like a political one; and yet it is a reckoning with masculinity, an expression of how clinging to its privileges can destroy intimacy and make a man feel lost. The legacy Western Stars taps traveled similar ground when artists like Bill Withers or Marvin Gaye carried it into soul. “Gotta keep movin’,” Gaye sings in “Trouble Man,” exuding machismo but also deep disquiet. The song’s sumptuous groove soothes but the voice at its core unsettles. A trouble man is a troubled man.

Western Stars sends this message, too, from a different point in time. The antiheroes Springsteen brings to life are not young men playing fast and loose with their destinies; they’re not Easy Rider’s Wyatt and Billy, nor are they his own earlier takes on those same characters, the Spanish Johnnys and Eddies and ragamuffin gunners he created in the 1970s. The men who populate Western Stars have sought freedom and know its edges in an unfree world. He knows these men well; on some level, they are him. Honoring a musical legacy he loves, Springsteen finds new life in familiar stories. “All he wanted was to be free, and that’s the way it turned out to be,” McGuinn wrote in the song Springsteen shared so long ago. Western Stars finds new places where that line can lead.