‘American Taliban’ John Walker Lindh Set To Be Released From Federal Prison

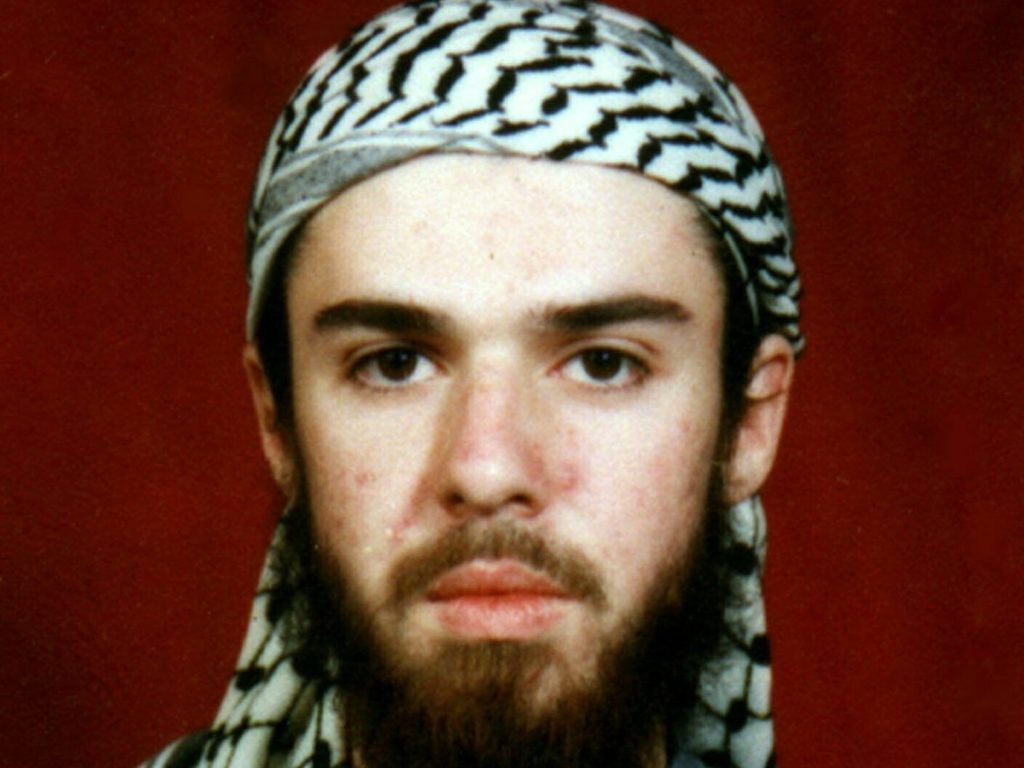

PHOTO: This image from television footage shows John Walker Lindh in Afghanistan on Dec. 1, 2001. Lindh was a Taliban soldier who was captured at that time. Having served 17 years of a 20-year sentence, he is scheduled to be released from a U.S. federal prison on Thursday. In the coming years, dozens of Americans linked to extremist groups are in line to be released from U.S. prisons. CREDIT: Associated Press

BY GREG MYRE

Bearded and bedraggled, John Walker Lindh became a focal point of American anger when the then-20-year-old from Northern California was found among the ranks of Taliban soldiers captured in Afghanistan less than three months after the Sept. 11 attacks.

He’s still known as the “American Taliban,” and some called him a traitor who deserved the death penalty. But Lindh, now 38, is scheduled to be released from a federal prison in Terre Haute, Ind., on Thursday after serving 17 years of a 20-year sentence.

He’s getting three years off for good behavior, though his probation terms include a host of restrictions: He needs permission to go on the Internet; he’ll be closely monitored; he’s required to receive counseling; and he’s not allowed to travel.

He remains a lightning rod for critics who say his sentence was too lenient and he shouldn’t be allowed out early. At his sentencing in 2002, Lindh said, “I have never understood jihad to mean anti-Americanism or terrorism. I condemn terrorism on every level, unequivocally.”

Some reports, citing government assessments, say Lindh supports radical Islam, though his family disputes this and he has not been allowed to speak publicly while in prison.

John Walker Lindh at an Islamic school in Pakistan where he studied from 2000 to 2001. CREDIT: AP

A CIA paramilitary officer, Mike Spann, was killed in a prisoner uprising at the military compound in northern Afghanistan where Lindh and other Taliban prisoners were being held in 2001.

Lindh was never charged with involvement in that death. But Spann’s family remains critical, saying Lindh failed to warn Spann of the looming uprising. Spann’s daughter, Alison, a child at the time of her father’s death, posted on Twitter:

“I feel his early release is a slap in the face — not only to my father and my family, but for every person killed on Sept. 11th, their families, the U.S. military, U.S. intelligence services, families who have lost loved ones to this war and the millions of Muslims worldwide who don’t support radical extremists.”

There has been no word on where Lindh will live or what he will do. His parents, who are in Northern California, have been supportive of him.

More Cases To Come

While Lindh’s saga has received intense scrutiny, it points to the dozens of lower-profile cases where Americans linked to extremist groups will be released from prison over the next several years.

The U.S. has not established any organized program to deal with them. To date, Americans once imprisoned for ties to radical Islamist groups have not emerged to carry out attacks in the United States. Some foreign extremists detained at the U.S. prison in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, have returned to the battlefield abroad after they were released.

Lindh was born in Washington, D.C., where his father, Frank Lindh, graduated from Georgetown Law and worked for the Justice Department. The family moved to Marin County, outside San Francisco, when Lindh was 10.

Raised as a Catholic, at 16 he converted to Islam. With support from his parents, he went to Yemen to study Islam and Arabic and then went on to Pakistan in 2000. The following year, he crossed the border to Afghanistan to volunteer as a Taliban soldier.

“Here’s where John starts to get himself in trouble,” Frank Lindh said in 2013. “It never crossed our mind that he would go into Afghanistan, but that’s what he did in spring of 2001.”

Lindh and his family say he went to help the group as it battled other Afghan factions, though the Taliban’s own abuses were widely known at the time.

In the summer of 2001, Lindh was at a Taliban training camp when al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden visited. The two spoke briefly, according to Lindh’s father.

The Taliban sent Lindh to the far northeast of the country shortly before al-Qaida’s Sept. 11 attacks in the United States. He remained with the Taliban until a group of several hundred surrendered near the end of November.

9(MDAyOTk4OTc0MDEyNzcxNDIzMTZjM2E3Zg004))