BOOK REVIEW: ‘Becoming Dr. Seuss’ Reveals Theodor Geisel As A Complicated Icon

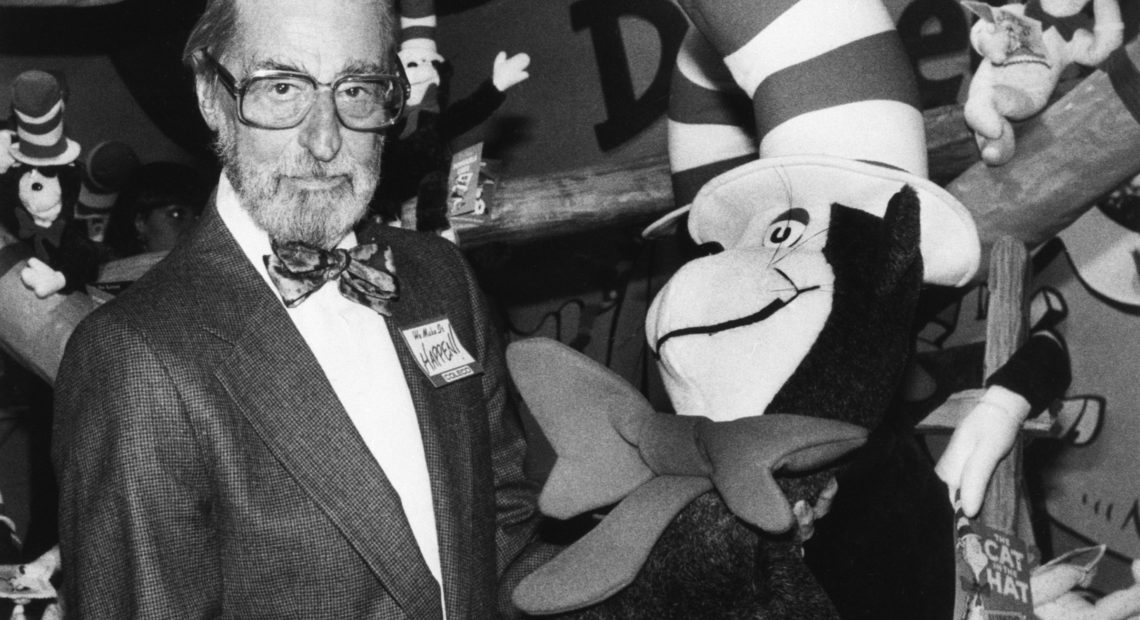

PHOTO: Theodor Geisel — Dr. Seuss — holds a toy of the Cat in the Hat, one of his most famous character creations.

BY GABINO IGLESIAS

Theodor Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, was an American icon.

But he was also a complicated man who saw children’s literature as a step down in a writer’s career and whose work was stained with misogyny and racism, as highlighted in Brian Jay Jones’ Becoming Dr. Seuss: Theodore Geisel and the Making of an American Imagination. This and other dichotomies are at the core of Jones’ book: Geisel was loved by millions of children but couldn’t have children of his own; he wanted his work to be published but panicked when he had to talk about it publicly.

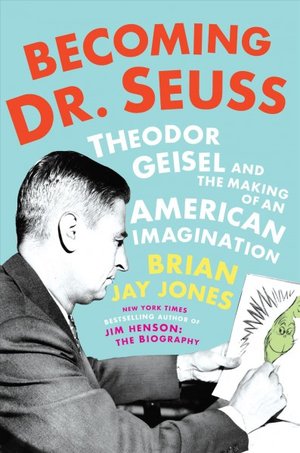

‘Becoming Dr. Seuss:

Theodor Geisel and the Making of an American Imagination’ by Brian Jay Jones

Nuanced, profoundly human and painstakingly researched, this 496-page biography is perhaps the most complete, multidimensional look at the life of one of the most beloved authors and illustrators of our time.

Becoming Dr. Seuss is an expansive biography that tracks Geisel’s life and roots from 1904 to 1991. The book is divided in stages and pays equal attention to every step of Geisel’s journey. While it is a standard biography in general terms, Jones goes above and beyond to contextualize Geisel in the larger picture at every moment of his life. This makes Becoming Dr. Seuss a fascinating read that discusses the origin of the humorous, simple rhymes, bizarre creatures, and magic that characterized Geisel’s books while also showing the author’s more radical side as an unemployed wanderer who abandoned his doctoral studies, a successful advertising man, and a political cartoonist.

Contrast and contextualization make this biography special. Also, the most interesting thing about Geisel’s journey, especially in the early years, is how unremarkable it was. Geisel wasn’t a brilliant illustrator from the start and his writing wasn’t great from the get-go. In fact, he worked at both for years, turning in work that ranged from slightly funny and unique to mediocre and immediately forgettable. That he managed to become an international sensation is a testament to his perseverance, Jones shows.

Jones engages with Geisel’s darker side fearlessly. For example, Geisel wasn’t studious. His fellow Casque & Gauntlet (the second-oldest society at Dartmouth College) members unanimously voted him Least Likely to Succeed. Classmate Frederick Blodgett declared in an interview: “He never seemed serious about anything.” That laissez faire would be present for most of his 20s: “His year at Oxford had been a bust, and his plans for a teaching career had dissolved with his unattained doctorate. His future was uncertain, and his prospects for employment were cloudy at best,” Jones writes.

Geisel moved to New York City in the Jazz Age. The world, states Jones, was becoming “bigger and louder.” Unfortunately, racism and misogyny were part of the picture. Geisel used racial epithets and drew cartoonish characters of African Americans, Arabs and Asians. However, Jones notes, he never thought he was doing anything wrong and considered he was working “within the norms of the era, relying on the language and cartoon stereotypes he’d been reading and seeing in the mass media since childhood.”

After a series of lucky encounters, Geisel’s career as Dr. Seuss took off. Jones’ writing of everything that led to that, which takes up the first third of the book, is outstanding. From then on, Geisel would always remain a creative force that was also full of contradictions. Furthermore, he lived inside his head, getting “bored easily and looking for other things to do.” In 1986, for example, he was well-known already but his nature remained unchanged:

“At a charity gala at the high-end Neiman Marcus department store in San Diego, Ted disappeared for hours. When [his wife] Audrey finally found him, he was sitting in the women’s shoe department, happily switching all the prices around.”

Geisel would go on to publish 48 books in more than 20 languages. Although it took a while to sell, his first book, And to Think I Saw It on Mulberry Street, received glowing reviews in The New York Times, The Atlantic and The New Yorker. Still, Geisel saw writing books for children as, in his words, “a step down. A loss of face … literary slumming.” Those numbers and facts are real. The ones he talked about, however, were as full of imagination as his books. He changed stories often, using what Jones calls “dramatic embellishments”: How he proposed to his wife and the rejections his first book received are just two of many narratives that have multiple versions.

Geisel turned in Oh, the Places You’ll Go! in 1989. Readers and critics saw it as “Dr. Seuss’s final and beneficent words of encouragement and support for anyone, at any age, anxious to make their way in the world.” It would help the world remember him as an immense creative force and positive figure. Jones accomplishes the same with this book. Using personal papers, articles, telegrams, biographies, unpublished interviews, and letters, Becoming Dr. Seuss gives readers a comprehensive view of a complex, multifaceted creator who became a giant.

This biography adds to Geisel’s legacy and Jones’ message is clear: “While Theodore Geisel may be gone Dr. Seuss, of course, goes on.”

Gabino Iglesias is an author, book reviewer and professor living in Austin, Texas. Find him on Twitter at @Gabino_Iglesias.