Herbie Hancock Aims All-Star Jazz Day Concert Toward A World In ‘Turmoil’

BY NATE CHINEN

Herbie Hancock took a moment during the International Jazz Day All-Star Global Concert to address some fraught geopolitical realities.

Not that Hancock, in his dual capacity as UNESCO goodwill ambassador and chairman of the Herbie Hancock Institute of Jazz, got into specifics, or really needed to. Speaking from a podium at Hamer Hall in Melbourne, Australia on Tuesday night, he just extolled the spirit of cooperation and exchange in jazz, “at a time when internal and external relationships among so many countries are unsettled.”

The singer Lizz Wright, performing during the International Jazz Day 2019 All-Star Global Concert at Hamer Hall on April 30, 2019 in Melbourne, Australia. CREDIT: Graham Denholm/Getty Images for Herbie Hancock

Moments earlier, Hancock had been seated at a grand piano playing a tune by his friend Wayne Shorter — “Beauty and the Beast,” a slow-funk saunter from an album Shorter made with the iconic Brazilian troubadour Milton Nascimento. Standing in for Shorter was a Dutch saxophonist, Tineke Postma, alongside musicians originally from India, Mexico and Brazil.

This was the eighth annual edition of International Jazz Day, which has always carried a frank subtext of diplomacy along with its ambient hum of positivity. Hancock, 79, designed the event around a hopeful conviction: that jazz’s value system could be applied to a humanitarian cause. As in past years, Jazz Day brought a small army of musicians to its designated host city for several days of educational workshops and performances, culminating in the All-Star Concert. There were also celebrations across the globe, in 195 countries and on every continent.

The concert’s opening invocation deftly communicated a sense of place and purpose. James Morrison, an Australian jazz luminary who served as Hancock’s artistic co-director, emerged at center stage with his trumpet. Beside him was William Barton, a virtuoso and scholar of the didgeridoo, the instrument of his aboriginal people. Together they improvised a series of whooshes, barks and cries; the interplay was loose but locked in, and the effect transfixing.

Left unspoken in the performance was a point Barton made later, in conversation: “We’re unified onstage together. We’re speaking as one voice.” The cultural implications of that unity, for these two artists in particular, imparted a poignancy that the concert could build on and carry forward.

That it did, without making an undue fuss or overstaying its welcome, is a credit to all the musicians on the concert — especially pianist John Beasley, in his customary role as musical director. Under his direction, the evening compressed dozens of musicians into a brisk program that easily could have felt draggy or overstuffed. (In some past editions, it has.)

Because each artist had a small window for expression, the performances often felt boiled down to an essence. This was true of Kurt Elling and Jane Monheit, two jazz singers equal in their warm effusions of personality, but otherwise as distinct as night and day. It was true of another pair of singers, Somi and Ledisi, in two soulful showstoppers. And it was emphatically true of Lizz Wright, relaxed and radiant in a gospel mode, backed by a dream team, including organist Joey DeFrancesco, guitarist Jeff Parker, pianist Eric Reed and drummer Brian Blade.

The Australians on the concert, including Morrison, guitarist James Muller and trumpeter Mat Jodrell, were the picture of smart versatility and easygoing prowess. In that sense they were apt ambassadors for a jazz community that calls to mind a beehive: self-contained, productive and teeming, though you might need a peek on the inside to tell.

Jodrell timed the release of a new album, Insurgent, for International Jazz Day, pointedly enlisting a nearly all-Australian band. “For a town of this size to have at least 10 dedicated jazz clubs that are running most nights of a week, it’s amazing,” he said, referring to Melbourne, where he lives. “And it seems to be getting bigger all the time.”

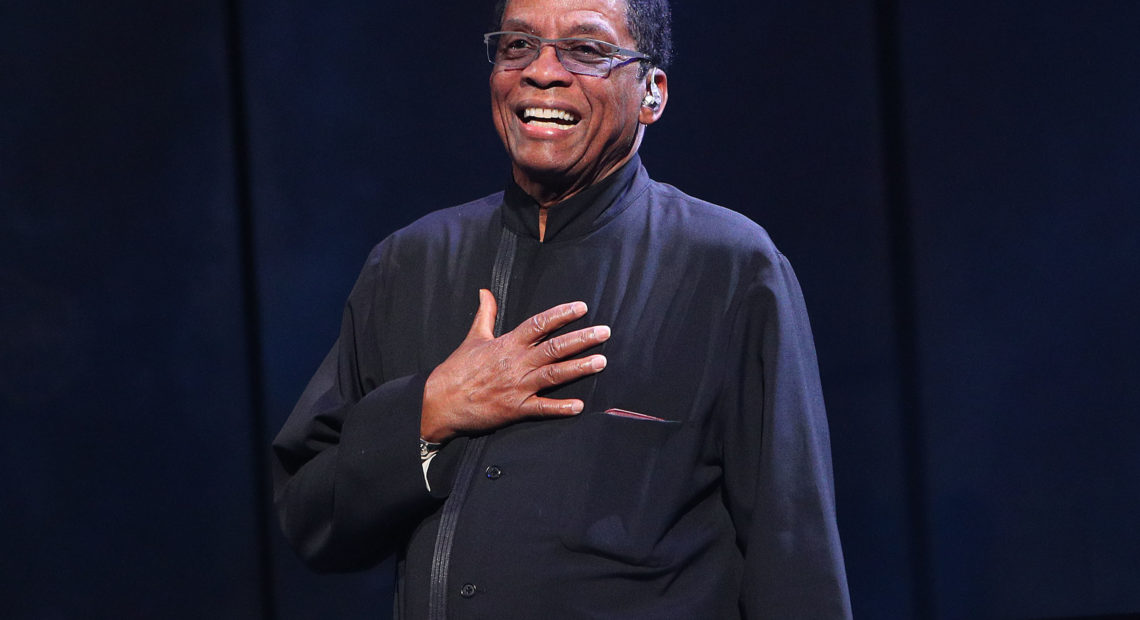

“It’s about more than being American, or Australian, or any particular group. But it celebrates the cultures of all the groups. This is what jazz really does,” Herbie Hancock tells NPR. Here, Hancoock is pictured onstage during the International Jazz Day 2019 All-Star Global Concert. CREDIT: Graham Denholm/Getty Images for Herbie Hancock

Morrison echoed the endorsement: “There have been times in Australia’s history where you could easily argue that Sydney was the center of what was going on,” he said. “It is certainly Melbourne’s time now. Jazz Day is not making Melbourne what it is, but rather acknowledging what it has become.”

Part of what Melbourne has become, as any visitor can attest, is a true melting pot — a native land turned Victorian port city shaped by all manner of Asian, European and Middle Eastern influence. You could hardly dream up a more promising point of convergence for the message of International Jazz Day, as Morrison demonstrated with a set piece near the middle of the concert.

It involved a far-flung assembly of musicians interpreting a traditional Persian theme, “Melody in Esfahan.” Along with Morrison and Barton, the ensemble included A Bu, from China, on piano; Aditya Kalyanpur, from India, on tabla; and Antonio Hart, from America, on saxophone. Working with Blade and bassist Ben Williams, they found common ground, opening up the song.

The earnest multinationalism of this gesture — a hallmark of the Jazz Day concert, which ended this year as it always does, with John Lennon’s “Imagine” — runs contrary to a lot of political rhetoric of the moment. I had detected more of an edge than usual in Hancock’s affirmations about peace and unity, and after the concert I asked whether he felt more urgency in his mission.

“Absolutely,” he replied. “I mean, the world is in turmoil right now. Not just in the countries that we’re calling conflict zones.”

As a Jazz Day jam session rattled happily across the room, Hancock bore down on his point.

“The purpose of this event is to show, through the music, the kind of world that we can live in if we work toward those goals, of respecting everybody,” he said. “It’s about more than being American, or Australian, or any particular group. But it celebrates the cultures of all the groups. This is what jazz really does.”