Folk Singer Pete Seeger’s Legacy Immortalized With ‘Smithsonian Folkways’ Collection

LISTEN

BY AUDIE CORNISH & ART SILVERMAN

Though Pete Seeger, the heralded folk singer, songwriter and social activist died in 2014, his voice has left a lasting impression on American music. May 3, 2019 would have been Seeger’s 100th birthday and to mark the centennial, Smithsonian Folkways is set to release a six-CD collection titled Pete Seeger: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection.

This expansive collection features 20 previously unreleased tracks that spotlight Seeger’s pacifist methods, environmental activism and straightforward, inquisitive songwriting style. The collection also comes with a 200-page book on Seeger, written by Smithsonian Folkways curator and archivist Jeff Place.

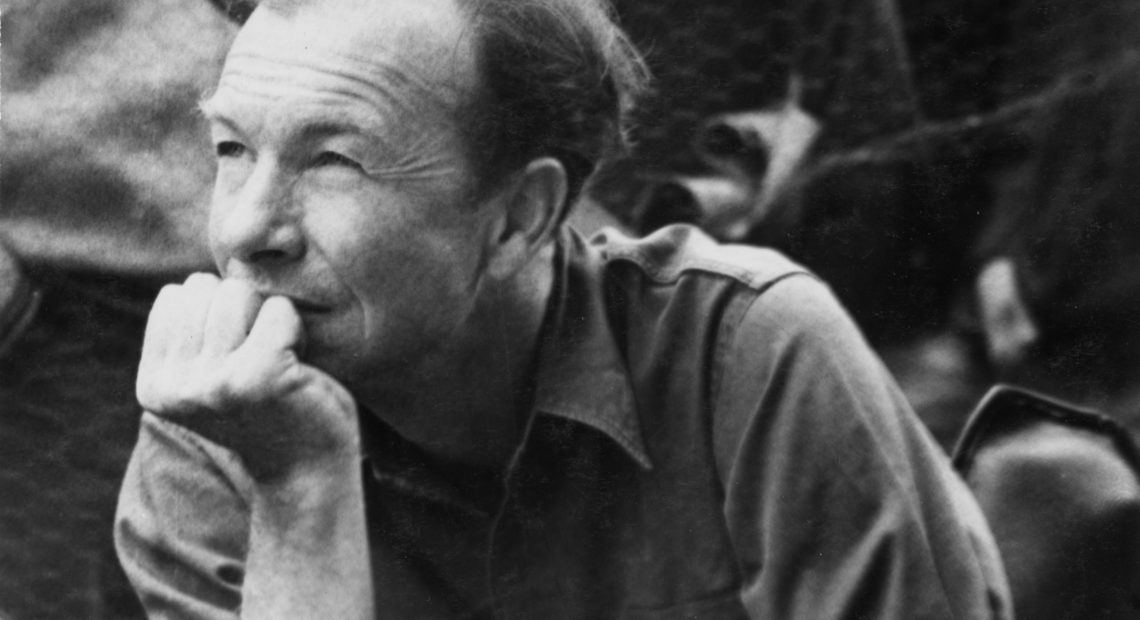

Pete Seeger: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection is a six-CD collection of Seeger’s previously unreleased music, accompanied by a 200-page book.

CREDIT: Diana Davies/Courtesy of the artist

Place spoke with NPR’s Audie Cornish about Seeger’s exploration period while fighting in World War II, the timelessness of his records and his impact on American folk. Hear the radio version of their conversation at the audio link and read on for more that didn’t make the broadcast.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Audie Cornish: We know him as someone who borrows and brings to the mainstream certain things he finds in other cultures. What did you learn about Pete Seeger as a writer looking through his papers?

Jeff Place: He was a great writer. He had a column called “Appleseeds” and a magazine called Sing Out for many, many, many decades and a number of different books where he sort of wrote about the work that he was doing.

And, in a way, thought of his work as journalism.

Yeah, he was great on going and finding these little, like, quotes in political history books and other books. You know in literature and in kind of taking them out and using them in his columns. Like the song “Where Have All The Flowers Gone” came out of a Russian novel. He found a line in there which inspired him to do “Where Have All The Flowers Gone.”

I want to talk about some of the songs that were never released. One of them that’s featured here was recorded in the 1940s. Pete Seeger was sent to war, he was stationed in the Pacific and in the collection you have a series of his letters. What was he writing about? And what do we come to understand about this period?

Well, you know, Pete Seeger was in the service and in the Pacific and hanging out with folklorists a lot, you know. So, he kind of went over there and he used the opportunity to record indigenous people from that part of the world and he recorded a lot of other soldier songs. He had this sort of [what] looked like a mimeograph letter or something he’d sent home to all his friends reporting on his findings called “Reports from The Marianas.”

We think of Seeger as a pacifist. What do you learn from that period about how he came to that position?

I once heard an interview Pete you being asked by a member of the remembers the audience and he was saying, “Well, Mr. Seeger, you don’t believe in war ready for any cause?” And he said, “No, that’s not true. There was a time period in 1940s when there was a reason to fight for the cause. And I was there and I would do it again if it happened again.”

This song “Ballad of Dr. Dearjohn” was recorded in 1963. How did you find it in the collection?

The thing about Folkways Collection and Pete Seeger and he put out 70 albums for Folkways and he also put out three or four hundred extra tapes of additional material that was never used. So I started going through all those tapes and I found this song that had been written and published in a magazine called Broadside. And what was interesting about it, it was contemporaneous to 1962 and the Canadian health care law, the Saskatchewan Law, and the debates and the song were identical to the whole thing we’ve been hearing about Obamacare in the last few years.

The thing was, you’ve got to go back many hundreds of years and before there was, you know, all this media and radio television and all this. What would happen is political events or satires would happen and someone would write a satirical song or a topical song about it and they’d publish it on pieces of paper, selling for like a nickel. They were called broadside ballads. So, this is all sort of out of that tradition of people who are trying to write broadside ballads in the 1960s.

Now, Pete Seeger was born in New York City and the Hudson River was important to him, especially as he lived further up the river and later years. Can you tell us the story behind the song “Of Time And Rivers Flowing”?

Yeah, Pete, he spent years and years traveling the country and all over the world, actually, in the ’60s. He was one of the first guys to sing multicultural songs and things like that. And somewhere along the line, apparently it dawned on him that he actually never paid any attention to where he actually lived [and] what was going on there. He says, “I’m a total stranger in my own hometown when I go home.”

He’d notice there was, like, sewage floating in the river. But he got to know the shad fishermen. the shad fishermen would take him out and show him all this like you know environmental damage and so, he wrote this song for the shad fisherman.

He really tried to build movements through his music, or at least connect to movements through his music. How does that connect to what you see going on on the landscape today?

He has like, what they call Pete’s children. It’s a lot of movements he was part of that he didn’t really start or you know he had lent his hand to, like Civil Rights Movement and things like that. But I think that the environmental thing on the river was really kind of Pete. He thought it was just like completely insane thought that he was gonna build this this boat, a sloop, and sail up and down the bay and, you know… playing music and stuff. But he did it and there’s still a festival up there every year and all these people who come and there’s still people who are going up and down the river in that boat, even after Pete’s gone.

9(MDAyOTk4OTc0MDEyNzcxNDIzMTZjM2E3Zg004))