Nearly four years ago, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee touted a new company that was coming to Kalama to revolutionize the methanol market.

On that sunny August day on the banks of the Columbia River, Inslee spoke alongside city and county leaders, business people and executives from NW Innovation Works (NWIW), a Chinese-backed company looking to build three massive natural gas to methanol plants in southwest Washington.

“I think this bodes well for Washington’s future,” Inslee told the crowd.

The governor praised the creation of hundreds of family-wage jobs, millions of dollars in local tax revenue, and the plant’s biggest selling point: the methanol it created from natural gas could help clean up China’s plastics industry.

The project has been pitched by its developers and the governor as one way to combat climate change. They say making methanol from natural gas in plants that use renewable power could eventually displace many of China’s dirtier coal-based plants.

“This is a fantastic step forward, because the carbon savings will be equivalent to taking millions, perhaps 6 million cars, off the road,” Inslee said in a promotional video at the time.

But the climate change-crusading governor currently running for president may not have known that NWIW was selling a different story to investors — one less focused on producing cleaner methanol for plastics and more on an opportunity to buy into a new methanol supply chain to fill China’s insatiable appetite for fuel.

Documents obtained by OPB show that NWIW is saying one thing to state regulators while eyeing China’s fuels market. As recently as January 2019, PowerPoint presentations shown to potential investors in the Kalama facility detailed the company’s apparent intent to burn their methanol for fuel in China.

This directly contradicts what the company has been publicly emphasizing for years, that its end product would only be used for olefins, the building blocks of plastic.

Washington has increasingly resisted the fossil fuel industry that has descended upon the state in recent years. Environmentalists have especially scrutinized energy projects looking to export fuel.

If a project like the one in Kalama were to go down that path, it could call into question the project’s current environmental impact analysis, and might even qualify for a more stringent regulatory path such as the state’s Energy Facility Site Evaluation Council, or EFSEC, a one stop siting process for major energy facilities in Washington. Fierce local opposition already shuttered plans for NWIW to open a Tacoma methanol plant, and plans for another in Port Westward, Oregon, are on hold.

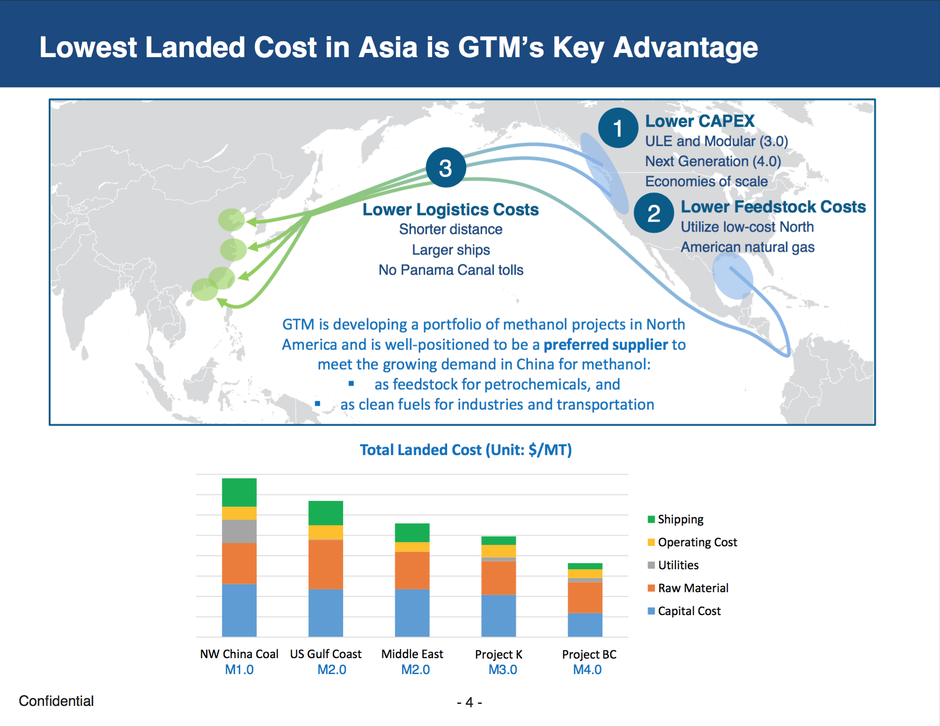

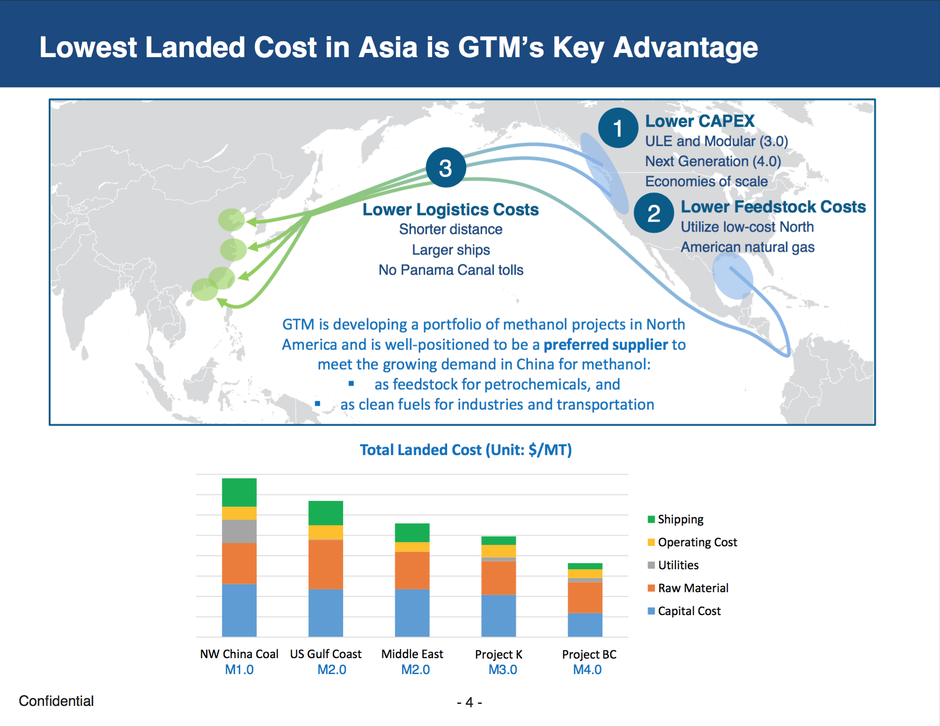

In a March 2018 PowerPoint presentation shown to Satori Partners Inc., a U.S.-based investment group with experience doing business in Asia, NWIW lays out a proposal with a very different product. More than a dozen pages discuss burning methanol as “clean fuels for industries and transportation.”

One slide features a ship carrying “liquid sunshine” and refers to the methanol produced in Kalama as “clean crude” and “convenient LNG.”

In the 26-page presentation, only one slide is devoted to methanol-to-olefin production or plastic materials. That narrative flies in the face of everything developers have told the public — and state regulators in the middle of determining whether the project moves forward.

“Obviously the reason that they’re not telling people, or going out of their way to say it’s not for fuel, is because that makes the greenhouse gas analysis less favorable to them,” said Dan Serres, conservation director of environmental group Columbia Riverkeeper, referring to the company’s most recent environmental review that is supposed to take into account the cradle-to-grave emissions of the project and its end product.

“This changes the analysis quite significantly if this isn’t going into the plastics manufacturing industry,” Serres added.

Riverkeeper has challenged earlier permits issued to the company and have been vocal opponents of the Kalama methanol plant, along with other fossil fuel industries that have eyed the Northwest for potential sites.

The documents were shared with OPB by Columbia Riverkeeper and Satori co-partner Steven Taracevicz, who says he and his Shenzhen, China-based partner were approached by NWIW to invest in the Kalama project in late 2018.

Taracevicz said his company was approached by NWIW leadership, including current CEO Simon Zhang and the company’s former CFO Edward Sappin, who authored the leaked presentation.

A screenshot from a PowerPoint presentation shows NW Innovation Works touting access to China’s fuel market as a major benefit of a proposed Kalama, Washington, methanol plant.

Despite presentation slides that show an arrow on a map from Kalama to images of Chinese trucks and cars in Asia, NWIW maintains all methanol produced at the Kalama facility will only be used for plastics and materials. A company official acknowledged that there is a demand for methanol as fuel but said that’s a “farther down the road” conversation.

Both PowerPoint presentations were sent by Taracevicz to Columbia Riverkeeper six weeks ago.

“This is certainly the most concrete piece of evidence that they really do consider this a fossil fuel export project,” said Riverkeeper attorney Miles Johnson.

Speculation that the company’s proposed Kalama refinery could tap into the methanol fuel market is not entirely new. On multiple occasions, project backers have voiced their intention to bring natural gas-created methanol into China’s fuel market.

Wu Lebin, chairman of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Holding Company, the main backer of the Kalama project, has publicly said the fuel will be burned as feedstock for fuel and industries.

In an April 2017 China Daily report, Lebin told reporters about his company’s $2 billion methanol plans, using the Kalama plant as evidence that China is investing heavily in North American shale gas “in order to commercially extract methanol for use as an environmentally sustainable motor fuel.”

Lebin went on to say his company is building “a supply chain for methanol, potentially China’s next alternative industrial and transport fuel,” according to a December 2017 article in Reuters.

NW Innovation Works also sponsored a two-day workshop at Stanford University in 2017 on methanol production titled “Opportunities and Challenges for Methanol as a Global Liquid Energy Carrier.” Conference reading materials fail to even mention using methanol to create olefins or plastics, again downplaying a point that is a major talking point when the company talks about its plans for the Kalama facility.

More recently, Lebin’s bio for an upcoming business conference for investors describes NWIW’s Kalama facility as “one of the most innovative clean energy projects in the nation” that will provide methanol “to China as clean feedstock for petrochemicals and fuels.”

NWIW confirmed the PowerPoint slides were indeed created by the company and presented to investors. However, they say mention of fuel was merely “educational” and that the methanol plant in Kalama was still on a pathway to be used for materials.

“Our desire is that the intentions and commitments for the materials use and pathway for NWIW Kalama project methanol be unambiguous,” Kent Caputo, the company’s COO and general counsel, wrote in an email to OPB. “Contractual and regulatory obligations and oversight can and should be put in place and enforced to ensure compliance with the intended and limited materials, such as methanol-to-olefin, outcome.”

Over the past decade, China’s appetite for methanol has grown considerably. Today, China is the world’s largest market for methanol, consuming anywhere from 60 million to 68 million metric tons per year, according to market analysts from S&P Global Platts. That’s more than half the global demand.

“That makes it a very important market from a global perspective,” said Esther Ng, senior editor for S&P Global Platts’ petrochemicals desk. Ng says the country’s domestic methanol production is about 58 million metric tons per year. The rest — the other 2 million to 10 million metric tons — is made up through imports.

“So China is always looking out for new sources of methanol,” she said.

China uses methanol for primarily two things: to convert into olefins for plastics and other materials or as a fuel for transportation and industries.

“We’re using methanol now in industrial boilers used to run manufacturing facilities, pharmaceutical plants, hotels and apartment complexes,” said Greg Dolan, CEO of the Methanol Institute, a Washington D.C.-based industry group.

Dolan says methanol is appealing to the Chinese government, especially when used to create products. By transforming the methanol in a plastic material, it traps the carbon from being released and reduces further greenhouse emissions. But he says that idea begins to get lost if the methanol is instead used as fuel.

“That’s an important distinction,” Dolan said. “If you are taking methanol and using it as a transportation fuel, then you’re burning it. Methanol will reduce a lot of emissions compared to gasoline or diesel. But it’s still a fuel that’s burning, and those produce greenhouse gas emissions.”

The debate over how much greenhouse gas emissions are released from the Kalama project and the ultimate use of its methanol are at the heart of a study requested by the state Shoreline Hearings Board. NWIW hired a consultant, California-based Life Cycle Associates, to complete a 241-page cradle-to-grave analysis that was included in the draft supplemental environmental impact statement (DSEIS), which is currently under review.

The study concludes that the Kalama facility’s use of liquified natural gas and the facility’s use of renewable energy would result in a reduction of global greenhouse gas emissions of between 9.6 million and 12.6 million metric tons per year. A large part of that hinges on the belief that this plant would displace coal-based methanol and would only be used to create plastics.

Environmentalists and climate researchers have been quick to pounce on this assumption, saying the argument that a Northwest methanol refinery will disrupt the coal-based methanol industry is not rooted in fact.

“It also relies on an assumption that natural gas is clean. But from a climate perspective, it’s not,” said Eric de Place, a director at the Seattle-based environmental think tank Sightline Institute.

He pointed to a study last year out of the Stockholm Environment Institutethat found faults with the LifeCycle analysis and believes the Kalama methanol facility would actually result in a net increase of greenhouse gas emissions.

“On environmental grounds, it’s a disaster,” said de Place, adding that the impact would likely be even worse if the company intends to sell the methanol to be burned as fuel.

A grain ship on the Columbia River at the Port of Kalama, which could one day also host a methanol plant. CREDIT: ASHLEY AHEARN. KUOW/EARTHFIX

Among those raising the question about the potential use as a fuel is the Washington Department of Ecology. In comments filed in the DSEIS, the state agency recommends that the final environmental impact statement more fully evaluate both potential uses of methanol: as a fuel and for olefin production and that the end products should be “quantified and included in the final net emissions calculations.”

“Once it leaves the state borders, there’s not much we know exactly what could happen to it, especially for a project that could last for decades,” said the state ecology department’s Neil Caudill, whose focus is greenhouse gas reporting and other climate reduction programs.

“That’s one of the reasons we’re wanting to be a little open-minded at this stage,” he said. “Because once we get the permits in place, 20 years down the line, it’s hard to reevaluate and change at that point.”

After reviewing the investor documents that suggest methanol produced in Kalama might be marketed as fuel, Inslee echoed points made by the ecology agency.

“This is an important question, and one that my Department of Ecology raised in December,” the governor wrote in an email to OPB. “We believe the final SEIS should address this issue.”

Port of Kalama spokesperson Liz Neuman said she wasn’t worried that Kalama methanol might be used for anything other than olefins.

Cowlitz County and the Port of Kalama are currently reviewing the LifeCycle analysis and thousands of comments from citizens, agencies and environmental groups. They’re expected to put together a final environmental impact statement in the coming months, before heading to the Department of Ecology for further scrutiny before key permits can be released.

OPB’s Cassandra Profita contributed to this story.

Copyright 2019 Oregon Public Broadcasting