Booked And Buried: After Dehydration Death, Grieving Father And Jail Chief Form Surprising Bond

Listen

NOTE: This story is part of the “Booked and Buried” series, a yearlong investigation and collaboration on jail deaths in Washington and Oregon. See more on the series here. Feedback on the series: news@nwpb.org

Four years ago this month, 25-year-old Keaton Farris died naked, dehydrated and malnourished on the floor of an isolation cell in the Island County Jail on Whidbey Island. Farris, who was bipolar and in the throes of a mental health crisis, had been arrested 18 days earlier for failing to appear in court for allegedly stealing and cashing a $355 check.

An investigation later found Farris’ death was the result of a series of individual and system failures. Jail officers had shut off the water to Farris’ cell after he flooded it, but then failed to ensure he received adequate water. Farris didn’t receive adequate health care in the jail. On the night he died, several hours went by without jail staff checking on him.

Farris was just one of at least 306 people who died between 2008 and 2018 after being taken to a county jail in Washington or Oregon, according to a recent investigation by OPB, KUOW and the Northwest News Network.

Farris’ death proved a galvanizing event. His family and supporters picketed the jaildemanding accountability. The jail’s director was suspended and a lieutenant was fired (she was later reinstated, but demoted in rank) after a sheriff’s investigation found that staff and supervisors failed to follow their own policies and procedures. Farris’ parents filed a lawsuit which they settled for $4 million. Later, two jail officers were charged with falsifying the log sheet showing how often Farris had been checked.

The story might have ended there. But it didn’t.

Grateful For A Hug

Photos of Keaton Farris hang in a hallway just off the kitchen in the home Fred Farris shares with his wife and two daughters near Coupeville. In one of the photos, taken a couple of years before his death, Keaton sits in a chair with his aunt’s striped cat on his lap. In another, he’s on the beach on Lopez Island where he grew up, staring out at the water.

There’s also a framed quote on the wall that’s attributed to Keaton: “I see your hate, and raise you one love.”

That’s the Keaton his dad wants to remember: The young man with a compassionate heart, the loyal friend, the loving big brother, the adventurer who dreamed of sailing around the world.

Instead, Farris said he feels like his son has been defined in death by his mental illness — which he’d been diagnosed with just three years earlier — and the fact he died in jail.

The last time Farris saw his son, he and his daughters were selling Girl Scout cookies. Keaton took a break from his job chopping firewood and visited them.

Keaton Farris died in the Island County Jail on April 7, 2015. Courtesy of the Farris family

“I was playing the tough love thing at that point,” Farris said.

Keaton had been charged with forging the check. His court day was looming.

“He was stressed out about it, but he told me at that point he’s really happy,” Farris said.

Before Keaton left, he gave his dad a hug.

“I’m grateful for that hug,” Farris said.

A month later Keaton was dead.

In his kitchen, looking at the photos of Keaton, Farris chokes up.

“It hurts because you don’t have any more times like that,” he said.

After his son’s death, Farris wanted the jail to make changes so that what happened to Keaton would never happen again. He also didn’t want Keaton’s death to be forgotten. He soon found a surprising ally.

An Unusual Friendship

On a recent Monday morning, the day after the fourth anniversary of Keaton Farris’ death, Island County Jail chief Jose Briones walked the length of the wharf in the picturesque town of Coupeville to a coffee shop called The Salty Mug.

Waiting for him outside was Fred Farris. The two shook hands and greeted each other warmly. It had been several months since they’d last seen each other. But meeting for coffee had become something of a ritual for the two men.

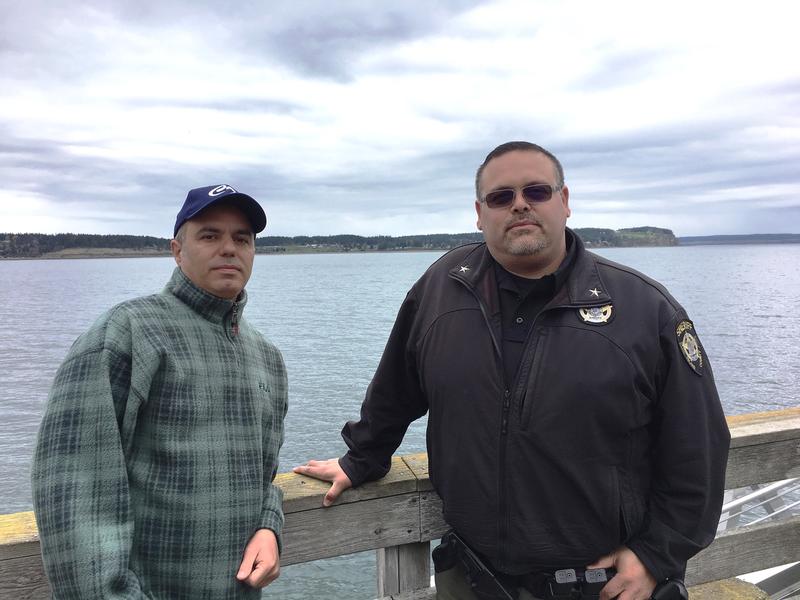

Sitting side-by-side at an outdoor picnic table, Farris, in a ball cap and fleece, and Briones, in his sheriff’s jacket and sunglasses, recounted the path to their unlikely friendship.

It began after Briones was hired to run the jail in December 2015, eight months after Keaton Farris’ death. Previously, Briones had worked Washington Department of Corrections where his responsibilities included overseeing a special unit for mentally ill inmates at the Monroe Correctional Complex.

Farris, by his own account, had been “banging the drum pretty hard” about who was going to run the jail following the retirement of the previous jail chief.

Shortly after Briones started, the Island County sheriff invited Farris to come meet the new chief. It was the beginning of what would evolve into an unlikely bond between the still-grieving father and the burly chief brought in to overhaul the jail’s operations.

Not long after that first meeting, Briones gave Farris a tour of the jail. For the first time, Farris saw the cell where Keaton died. “It was a rush of emotions, mostly sadness to think that he was alone and suffering in that small, cold place,” Farris recalled. During that tour, the two also talked about the internal changes Briones was implementing.

“You have to be transparent,” Briones said. “You have to say, ‘yeah this is where our faults are and these are the issues that we face and we want to get there, we want to make those important changes.’”

The settlement between the Farris family and Island County required that the jail “in good faith” consider the recommendations of a consultant brought in to review operations after Keaton’s death. The county also agreed to 18 months of monitoring by the consultant.

‘No One’s Going To Forget’

The 58-bed Island County Jail sits a few blocks from Coupeville’s historic waterfront district. The tan, two-story facility, built in the 1980s, is part of a sprawling county courthouse campus. Unlike modern direct supervision jails where correctional officers are in the unit with the inmates, Island County’s jail is an indirect supervision design. That means officers must physically walk around to check on inmates.

Even before Briones was hired, the jail had started making changes in response to Farris’ death. More changes happened once he was there. The county spent $180,000 installing cameras, including in the isolation cell where Farris died, and making upgrades to the jail’s electronic doors, locks and security systems. The jail went from having one part-time nurse to contracting two full-time nurses plus round-the-clock access to a medical provider. Jail staff received crisis intervention and suicide prevention training. These changes were first reported in 2016 by the Whidbey Daily News.

On a recent tour of the jail, Briones highlighted another upgrade. For inmates like Farris who appear to be incompetent to stand trial, the jail no longer needs to wait for a state psychologist to visit and do an in-person evaluation. Those evaluations can now be done by video, usually within two days.

But perhaps the most significant change is one that didn’t cost any money. Soon after taking the job with Island County, Briones set out to update many of the jail’s policies and to change the culture of the staff. As a part of that effort, he developed a new process for how jail staff must care for high risk inmates like Keaton Farris. In the jail’s policy manual, it’s titled “The Keaton Farris Process.”

“There’s a process named after Keaton because of what happened, and that will cause people to talk about it and not forget what happened and why it happened — and hopefully prevent it from happening again,” Briones said.

The process requires face-to-face security checks of all “special management” inmates with medical or mental health issues. The policy also requires shift supervisors and medical staff to visit these vulnerable inmates on a daily basis. Each week, the jail chief is required to review their status personally. In addition, the “Keaton Farris Process” instructs jail staff on the proper way to document all “safety checks” of these vulnerable inmates and the role of supervisors in reviewing those logs.

There have been no deaths in the Island County Jail since Keaton Farris died. Briones said there have been several suicide attempts and acts of self-harm since he arrived in late 2015, but in each case jail staff intervened in time to save the inmate.

Fred Farris said he’s thankful for the changes Briones has implemented and for his hands-on approach.

“I can never express to him how much I appreciate his role there and how far he’s helped Island County jail come,” Farris said.

But to this day, Farris is also frustrated because he doesn’t think there was enough individual accountability for the fact Keaton died from a lack of food and water, what he calls the “the most basic human needs.”

“The [staff] in there, they could have been the coldest people in the world, but if they just did their job, he’d still be here,” Farris said.

In the end, the two jail officers who forged the safety check logs pleaded guilty to gross misdemeanors and were sentenced to five days in jail plus community service.

Briones has a different view. He attributes Keaton’s death to a systemic failure. He says the jail staff didn’t know how to manage an inmate in crisis who was refusing food and water.

This difference of opinion is an underlying tension point in the relationship between Farris and Briones. But it hasn’t undermined Farris’ trust in the jail chief.

“Knowing there is someone in charge, doing their job with integrity and compassion is what gives me peace with Jose,” Farris said.

Remembering Keaton

Besides changes to the jail’s operations, Farris also wanted a permanent memorial so the community wouldn’t forget what happened to Keaton. But initially, Farris said, only one of the county’s three commissioners endorsed the idea. In a letter to Farris, the then-sheriff suggested if the family wanted to “memorialize Keaton” they could contribute funds to a mental health triage center or erect a bench at a county park. That wasn’t acceptable to the Farris family.

Fred Farris reads a note left at a memorial for his son Keaton who died in the Island County Jail in 2015. CREDIT: AUSTIN JENKINS/N3

Then one day, more than a year after Keaton’s death, a makeshift memorial to him on the jail grounds was removed. Gone were the flowers, photos and rocks that Farris considered a “living” memorial. He was angry and distraught. Farris stormed into the county commission offices and complained.

It was an insult to the family that would prove helpful in the end.

In a letter to Farris, County Commissioner Jill Johnson called the removal of the memorial “jarring” and said she would support a permanent remembrance. With two of the three county commissioners on board, Farris had enough support to move the project forward.

Farris worked with the county facilities director to select a location for the memorial near the entrance to the jail. But when it was time to decide what the memorial would say, his point-of-contact with the sheriff’s office was Briones.

Their relationship evolved as they worked together to decide what the plaque would say. Via email and text messages, they traded ideas for quotes. At one point Briones rejected one suggested quote because it used the word “broken” to describe someone like Keaton suffering from mental illness. Briones said he didn’t want to label people in crisis.

Ultimately, they settled on a quote from inspirational author Duane Dyer: “See the light in others, and treat them as if that is all that you see.”

“That quote embodies Keaton,” Farris said. “He really did see the magic in everybody he interacted with.”

Today, the plaque, which reads “In honor of Keaton Farris,” stands in a grove of trees not far from the entrance to the jail.

To mark the fourth anniversary of Keaton’s death, his friends left flowers and notes and someone tied a balloon the plaque. The day after the anniversary, Farris and Briones visited the site together. Farris picked up one of the notes that was tucked into a glass vase and read it aloud.

“My fellow Gemini with the same eyes, love you eternally.” It was from one of Keaton’s close friends.

Despite the initial opposition to the memorial, Briones said memorializing Keaton Farris inside and outside the jail was the right thing to do.

“Might not rub everybody the right way, but you know what I’m glad we did it because, you know, people shouldn’t forget,” Briones said. “That’s how you drive change.”

About the “Booked and Buried” series: During the course of the next year, OPB, KUOW and the Northwest News Network are teaming up to report on the epidemic of deaths at Northwest jails in our ongoing series “Booked and Buried.” If you have a tip or a story idea, email us: cwilson@opb.org, aschick@opb.org, austin@nwnewsnetwork.org or sydney@kuow.org.

Related Stories:

Jails In Washington And Oregon Have Higher Suicide Rate Than National Average

Since 2000, more than 200 people have died by suicide in Washington and Oregon jails putting the Northwest states above the national average for jail suicides, according to a new report by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Suicide Warning Signs Missed At Washington Prisons, Investigation Finds

For the second time in less than a year, Washington’s Corrections Ombuds (OCO) is warning that the state’s prison system needs to do more to prevent inmate suicides. In a 15-page investigation released Monday, the OCO found that two inmates died by suicide in 2020 after prison staff failed to recognize signs of mental distress and didn’t follow suicide prevention policies.

2nd Inmate Dies, National Guard Deployed To Help With COVID Testing At Eastern Washington Prison

Coyote Ridge has the highest number of confirmed coronavirus cases of any Washington state prison. The outbreak is concentrated within the Medium Security Complex portion of the prison, which houses more than 1,800 inmates. The total prison population is typically more than 2,400.