American Anthem: Katharine Lee Bates Asks How We Can Do Better In ‘America The Beautiful’

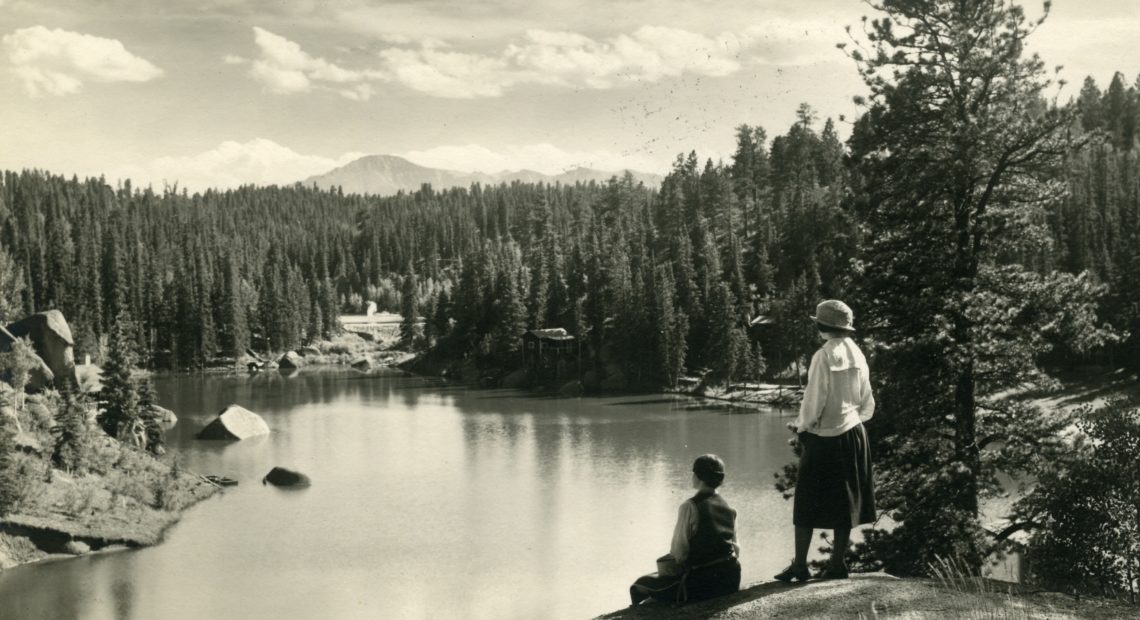

PHOTO: A view of Pikes Peak from the Carroll Lakes, circa 1925. Katharine Lee Bates’ trip up the Colorado mountain inspired her poem “America,” later to become the song “America the Beautiful.” CREDIT: Harry L. Standley/Courtesy of the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum

This story is part of American Anthem, a yearlong series on songs that rouse, unite, celebrate and call to action. Find more at NPR.org/Anthem.

LISTEN

BY ERIC WESTERVELT

In July of 1893, a witty feminist poet and Wellesley professor named Katharine Lee Bates scaled Pikes Peak, just outside Colorado Springs, Colo. She’d been teaching a summer session on Chaucer, and recovering from a suicidal depression earlier that spring. A brand-new railway up the 14,000-plus-foot mountain was broken, so Bates had to make it up the rocky path by horse-drawn wagon, and then by mule.

Even today, traveling by SUV, the road is intimidating: There are narrow switchbacks and astonishingly few guardrails. A park ranger warned me and my guide Leah Davis Witherow, historian and curator of the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum, to use the lowest gear on our way back down. On top of the windswept peak, though, it’s easy to see why Bates made the arduous journey.

Looking east, you can see almost all the way to Kansas. To the north, the Rocky Mountains stretch into the distance. And even on a bitterly cold and windy day, puffy clouds floated by, the sun hit the red rocks and the alpine evergreens were dusted with snow. “In the late afternoon, as the sun is shining and the shadows are coming over the mountains, the mountain looks purple,” Witherow explained during our visit. “It kind of radiates this purple glow, and it is beautiful.”

The view also overwhelmed Bates. She later wrote: “All the wonder of America seemed displayed there.”

Her poem “America” was first published on the Fourth of July in 1895, two years after her trip up Pikes Peak. She revised it in 1904, adding the lines, “And crown thy good with brotherhood / From sea to shining sea. It was later set to Samuel Ward’s tune “Materna,” and the modern “America the Beautiful” was born. It’s been what you might call the national hymn ever since.

The song and poem reflect a belief in community and social justice, values that came out of Bates’ hardscrabble upbringing on Massachusetts’ Cape Cod. Though she grew up rich in heritage, her grandfather having been a college president, the household where she spent her childhood was a poor one.

Living in Falmouth on the Cape, Bates’ minister father died when she was just a month old. To feed and clothe her four young children, her widowed mother had to be thrifty and find ways to share and barter. She sewed for neighbors, sold eggs and asparagus, and the Bates boys would chop wood for other widows.

“She said in her little autobiography that Falmouth practiced a kind of neighborly socialism,” says Melinda Ponder, author of the biography Katharine Lee Bates: From Sea to Shining Sea. “And I think by that, she meant that it was as her mother said: ‘Share and share alike.’ Katharine grew up seeing her mother put these principles into practice.”

As an adult, Bates and her close companion of 25 years, fellow Wellesley professor and social activist Katharine Coman, got involved in the reformist settlement house movement, helping organize a settlement home for immigrant workers in Boston. Ponder says the family’s challenges gave Bates a deep empathy and lifelong interest in helping those struggling to make ends meet: “She wrote a line about ‘not wanting to feast with the few,’ ” she says. “She wanted everyone to be included in whatever bounty there was.”

“America the Beautiful,” then, reads in part as a plea and a prayer for the United States to use its material wealth for the common good: “May God thy gold refine / Till all success be nobleness / And every gain divine.”

Another fateful trip in the summer of 1893 influenced how Bates viewed America, herself and her poetry. On her way to Colorado, Bates visited the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, which glorified turn-of-the-century industrial optimism and wealth. You can hear an appreciation for the progress of human civilization in the line “Thine alabaster cities gleam / Undimmed by human tears.” Bates knew the Fair’s “White City” was an unrealized, ideal vision.

At the same time, there was deep worry among intellectuals like Bates that industrialization, the growth of cities and the rise of mass culture were all making Americans soft — divorced from nature and one another.

“How do we come to terms with a newly mechanized world — a world where people were isolated from nature, a world where people punched a time clock?” Witherow says. “And then she comes west and she has this natural experience. She has these two diametrically opposing voices, or images, in her head: both of what’s best that can be built, and what’s best that is here by nature.”

In that sense, Bates’ poem and song were born during, and contributed to, the myth of the West: the American fantasy that a limitless frontier would serve as a source of perpetual rejuvenation, freedom and equality. Or, as Bates wrote, “A thoroughfare for freedom beat across the wilderness.”

In 1918, when the armistice ending World War I took effect on November 11, “From sea to shining sea” took on a more global meaning for Bates. Soldiers from the six New England states, known as the Yankee Division, stood in stunned silence near the French city of Verdun as the artillery ceased at 11 a.m. Soon after, those Americans walked out of their trenches, some in tears, and began singing “America the Beautiful.”

“She said she cried when she heard the story herself,” Ponder says. “She realized she had written a song that spoke or gave voice to these soldiers. They could picture their country that they loved and now would be able to come home to.”

If “The Star-Spangled Banner” boldly proclaims the country’s greatness as fact, “America the Beautiful” is more aspirational. Bates is not asking whether the flag has survived an artillery strike. Rather, this young feminist poet, who had just emerged from a deep depression, is asking if the nation, and perhaps the world, can ever live up to its high ideals.