Nearly 4,500 Older Brick Buildings In Washington Could Be Dangerous In Quake, New Report Says

Listen

The State of Washington has completed its first statewide inventory of buildings prone to crumble or collapse in an earthquake. The bottom line: There are an awful lot of unreinforced, old brick or stone buildings that could be dangerous — a similar number to estimates in Oregon.

The survey in Washington combined various databases of historic structures as well as commercial, government and apartment buildings completed before 1958. The project excluded single-family homes. The survey identified nearly 4,500 unreinforced masonry buildings that are confirmed or suspected to pose high risk in an earthquake.

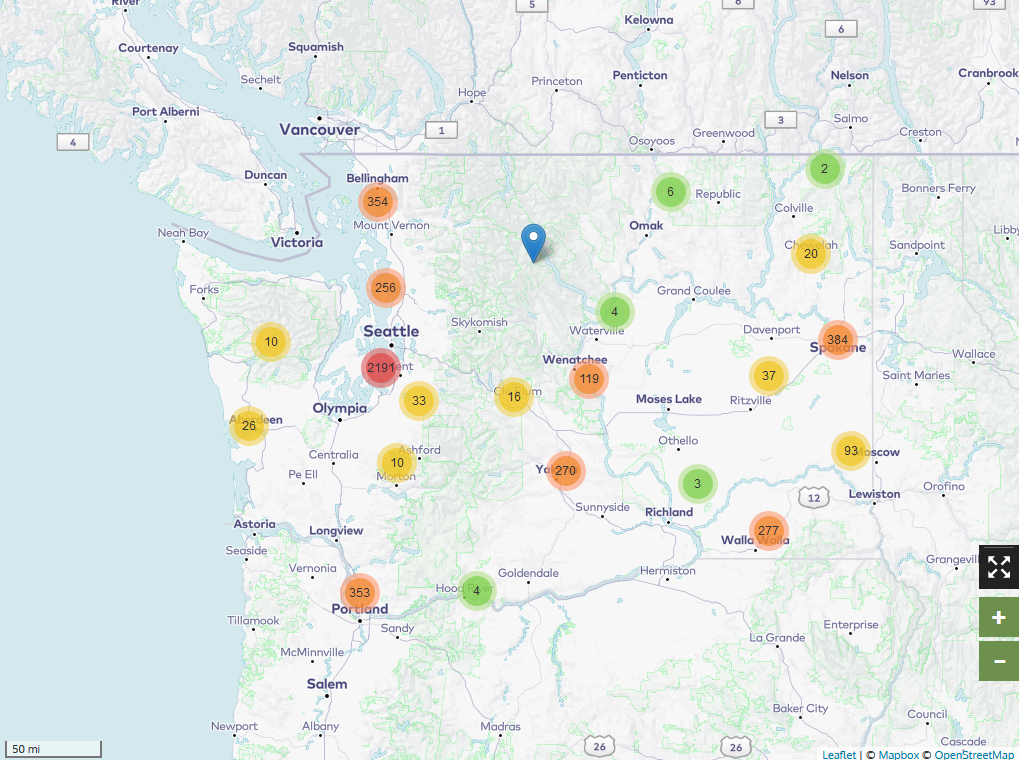

“I am initially shocked by how many there are, but also how widely spread they are across the state,” said Brian Terbush, earthquake and volcano program coordinator for Washington’s Emergency Management Division.

Damage from fallen bricks in Seattle’s Pioneer Square district after the 2001 Nisqually Quake.

CREDIT: KEVIN GALVIN / FEMA NEWS

“Once we know that these are the hazards and that these buildings are dangerous, we can start having a better conversation,” continued Terbush in an interview. “We can narrow down which buildings are the most important to retrofit and start prioritizing. That would be an excellent first step — whether we want to do schools or whether we want to do government buildings.”

Seismologists say the Pacific Northwest has entered the broad time window for the next rupture of the offshore Cascadia fault zone, also known as “The Big One.” The next earthquake could just as easily come from one of the many shallow, crustal faults that run underneath nearly all of the Northwest’s larger cities.

The Washington inventory identified 170 emergency facilities, such as hospitals and fire stations, that are housed in unreinforced masonry buildings — or URMs in technical lingo. Schools account for another 219 buildings on the list.

An interactive online database shows down to the city block where vulnerable buildings are, the year they were built and whether the construction style is known or merely suspected to be dangerous in an earthquake. The largest number of shaky old buildings are in Seattle, but there are also pockets of hundreds of others each in Bellingham, Tacoma, Olympia, Spokane and Vancouver, Washington.

“As the state with the second-highest earthquake risk in the country, Washington must identify and validate the number of URM buildings and where they are located to understand the scope of the problem and what may be needed to address it,” wrote recently-departed state Department of Commerce Director Brian Bonlender in a letter to the governor and legislature accompanying the inventory report.

Washington’s statewide total of earthquake-vulnerable buildings comes close to the estimate for how many there are in Oregon: more than 5,000, according to a studyfrom the historic preservation nonprofit Restore Oregon. The legislatures in both states are debating whether to create new grant programs to subsidize seismic upgrades.

Over the past decade, the state of Oregon has awarded awarded tens of millions of dollars to strengthen brick school buildings as well as to reinforce older hospitals, fire and police stations. Next Thursday, a state House committee has scheduled a hearing to consider whether to establish an additional program to subsidize seismic upgrades to churches, commercial buildings and nonprofit-owned community halls.

In the Washington Legislature, the state Senate this month stripped out a proposed public matching dollar fund for earthquake retrofits to vulnerable privately-owned buildings from a pending seismic safety package.

Public matching money could tamp down some of the opposition from building owners to proposed mandatory retrofit rules in Portland and Seattle, although the pacifying effect could be limited by the lack of money actually being made available to the private sector. Building owners in Portland in particular have vocally resisted mandatory retrofit requirements.

When there is money to retrofit a vulnerable building, common fixes include strengthening exterior walls and reinforcing junctures between floors or ceilings and those walls. Another frequently recommended safety enhancement is to tie down parapets and cornices, which could otherwise rain down bricks or stones onto the heads of people passing below.

Related Stories:

Rehearsing For ‘The Big One’ On A Room-Sized Chess Board

Close to 200 federal, state and tribal emergency preparedness planners gathered around a giant map of the Pacific Northwest this week to rehearse and critique the federal response plan for “The Big One.” The three-day Cascadia earthquake discussion exercise partially replaced a much bigger planned dress rehearsal that was canceled due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Are You ‘Two Weeks Ready’ For Post-Quake Survival? WA And OR Say You Should Be

The state of Oregon has set an ambitious goal to prepare more families in earthquake country to be “two weeks ready” after a disaster. Washington’s emergency management agency is also seeking more funding to prepare people in a similar way.

Seismic Research Ship Goes Boom-Boom To Seek Answers At Origin Of The Next Big One

Earthquake researchers are eager to dig into a trove of new data about the offshore Cascadia fault zone. When Cascadia ruptures, it can trigger a megaquake known as “the Big One.” The valuable new imaging of the geology off the Oregon, Washington and British Columbia coasts comes from a specialized research vessel.